Introduction

Google Docs is a collaborative editor where a user creates a document, edits text, invites collaborators, and restores earlier revisions. The system streams edits in real-time, merges concurrent operations, shows cursor positions, records revisions, and enforces permissions on every read and write, including share links.

At scale, the system must deliver low-latency updates, stay highly available during spikes, keep documents consistent for all collaborators, store a durable revision history, and apply secure sharing rules.

Functional Requirements

We extract verbs from the problem statement to identify core operations:

- "creates" and "edits" → Single User Editing

- "streams" → Live Edit Streaming

- "merges" → Concurrent Edit Convergence

- "shows" → Cursor & Selection Presence

- "shares" → Sharing & Permissions

- "restores" → Version History

Each verb maps to a functional requirement that defines what the system must do.

-

Users can create, open, update, and delete their own documents in the browser.

-

Edits made by one user appear to other collaborators in near real time.

-

Simultaneous edits from different users should converge to the same final document state.

-

Users should see collaborators' live cursors and text selections.

-

Users can share documents with others and control access levels.

-

Users can view previous revisions and restore a document to an earlier version.

Scale Requirements

- DAU: 1 million

- Traffic spike: 5x during peak hours

- Read to write ratio: 10:1

- Average document size: 100KB

- Average documents per user: 10

- Edit frequency: 1 edit per second per active document during peak

- Allow up to 100 concurrent users per document

Non-Functional Requirements

We extract adjectives from the problem statement to identify quality constraints:

-

"real-time" and "low-latency" → Updates must arrive quickly for collaborators.

-

"consistent" → All replicas must converge to the same document state.

-

"durable" → Edits and revisions must not be lost.

-

"secure" → Permissions must be enforced on every read and write.

-

"highly available" → Collaboration should continue even during traffic spikes.

-

Low latency: Edits and cursor updates should feel immediate to collaborators, minimizing perceived lag.

-

Convergence: All users should eventually see the same final document state after concurrent edits.

-

Read-your-writes: A user should see their own edits immediately, even before others do.

-

High durability: Document content and revision history must survive failures.

-

High availability: The editor should stay usable during peak traffic and partial outages.

-

Security: Only authorized users can read or modify documents.

Data Model

Nouns extracted from the problem statement:

- "document" and "revision" → Document and Revision entities

- "operation" → Operation entity

- "permission" and "share link" → Permission entity

- "cursor" and "selection" are modeled as ephemeral presence state in the real-time layer, not a core persisted entity

Document

Core metadata for a document and the pointer to its latest revision.

Operation

Atomic edit operation sent by a client.

Revision

Point-in-time version metadata for history and restore.

Permission

Access control entry defining who can access a document.

Document and Revision have a one-to-many relationship. A document has many revisions over time.

Document and Operation have a one-to-many relationship. A document receives many operations from collaborators.

Document and Permission have a one-to-many relationship. A document has many permission entries.

API Endpoints

We derive API endpoints from the functional requirements (verbs):

- "create" and "open" → Document create/read endpoints

- "edit" → Operation submission endpoint

- "stream" and "show" → Real-time collaboration channel

- "share" → Permissions management

- "restore" → Revision history endpoint (restore flow discussed in design, not fully expanded in API)

/api/documentsCreate a new document

/api/documents/{documentId}Fetch document metadata and current content

/api/documents/{documentId}/operationsSubmit a batch of edit operations

/api/documents/{documentId}/historyList document revisions (used for version history and restore UI)

/api/documents/{documentId}/permissionsGrant or update access for a user

WS /api/documents/{documentId}/collaborateReal-time channel for operations and cursor presence

High Level Design

1. Single User Editing

Users can create, open, update, and delete their own documents in the browser.

Let's start with the simplest case: one user creates a document and expects it to still exist after a refresh. That means we need a stable document identity and durable storage.

Decision 1: How do we generate document IDs?

Our Choice: Use opaque, globally unique document IDs. This keeps URLs short, supports sharing, and prevents easy enumeration.

Decision 2: Where do we store metadata vs content?

Our Choice: Split metadata and content. The access patterns are different, and the split keeps each store doing what it's good at.

The architecture at this stage: the client calls the Document Service, which writes metadata to a relational database and stores the document body in object storage. We now have a durable single-user editor and a base we can extend for collaboration.

2. Live Edit Streaming

Edits made by one user appear to other collaborators in near real time.

So far we can store documents, but collaboration needs something new: a live channel that streams edits as they happen. If we only poll every few seconds, the editor feels laggy and we waste requests when nothing changes.

Decision 1: How do we push edits in real time?

Our Choice: Use WebSockets for bidirectional streaming.

Decision 2: How do we fan out edits across many gateways?

Our Choice: Use pub/sub fanout. Direct broadcast is fine at small scale, but pub/sub is the safer default once we run many gateway instances. (For a deeper dive, see Message Queue and System Design Template.)

How the flow works:

- Clients open a WebSocket to the Real-time Gateway.

- The gateway forwards each edit to the service layer for validation and persistence.

- After persistence, the service publishes the update to a message queue.

- The message queue fans out the update to every gateway subscribed to that document.

- Each gateway broadcasts the update to its connected collaborators.

The architecture at this stage: clients connect to the Real-time Gateway via WebSocket. Edits flow through the Document Service to storage, then fan out through a message queue back to all gateways. This adds real-time streaming without changing the underlying storage model.

3. Concurrent Edit Convergence

Simultaneous edits from different users should converge to the same final document state.

Live streaming is not enough. If two users edit the same sentence at the same time, each client can end up with a different result. We need convergence (all replicas reach the same final state), not just fast delivery.

Decision: How do we resolve concurrent edits?

Our Choice: Use a server-ordered OT-style pipeline. We already have a Collaboration Service in the middle of the edit flow, so a single ordering point keeps client logic simpler and gives us predictable convergence. (We'll compare OT vs CRDTs in the deep dive.)

How the flow works:

- Clients send edit operations to the Real-time Gateway.

- The gateway forwards them to the Collaboration Service.

- The Sequencer (per-document ordering component) transforms concurrent operations and appends the result to the Operation Log (append-only record of edits).

- The Collaboration Service updates the Document Service with the new state.

- The transformed operation is published to the message queue.

- The message queue fans out the update to all gateways, which broadcast to collaborators.

The architecture at this stage: the Real-time Gateway forwards edits to the Collaboration Service, which sequences and transforms them, stores them in the Operation Log, updates the document, and broadcasts consistent results to all clients.

4. Cursor & Selection Presence

Users should see collaborators' live cursors and text selections.

So far we are syncing content, but collaboration feels incomplete without presence. Cursor updates are frequent and short-lived, so we should treat them differently from durable edits.

Decision: Where should cursor data live?

Our Choice: Use an in-memory presence store with TTL-based cleanup. Presence is best-effort, so we prioritize low latency over durability.

How the flow works:

- The client sends

presence_updateevents over the real-time channel. - The Real-time Gateway forwards them to a Presence Service.

- The Presence Service updates the in-memory store and broadcasts the latest cursor state to other collaborators.

- Throttling and coalescing prevent overload, and TTL cleans up stale cursors.

The architecture at this stage: a Presence Service and in-memory presence store handle ephemeral cursor updates, while the core edit pipeline remains unchanged.

5. Sharing & Permissions

Users can share documents with others and control access levels.

Collaboration only works if access is controlled. Every read and write must check permissions, and those checks need to stay fast even as sharing grows.

Decision: Where do we keep permission data?

Our Choice: Use a dedicated Access Control Service with its own permission store. We get fast, consistent checks without bloating document metadata.

How the flow works:

- The Collaboration Service checks permissions before accepting edits.

- The Document Service checks permissions before returning content.

- Both services query the Access Control Service, which looks up roles in the Permission Store. Share links map to permission records with a role and optional expiry.

The architecture at this stage: we add an Access Control Service and Permission Store to enforce roles consistently across read and write paths.

6. Version History

Users can view previous revisions and restore a document to an earlier version.

After collaboration, users often need to recover from mistakes. Version history provides safety by letting them inspect and restore prior revisions.

Decision: How do we store revisions efficiently?

Our Choice: Use a hybrid approach. Periodic snapshots go to object storage, while deltas are appended to the operation log.

How the flow works:

- Users request revision history through the Document Service.

- The Document Service queries the Revision Store for revision metadata.

- The Snapshot Writer periodically reads from the Operation Log.

- It writes a revision record to the Revision Store.

- It stores the compacted snapshot blob in Object Storage.

Restoring a version updates the head_revision_id pointer and creates a new revision entry.

The architecture at this stage: the Collaboration Service continues to append operations, while the Revision Store and Snapshot Writer provide durable history and fast restores.

Deep Dive Questions

How do you decide between OT and CRDTs for conflict resolution?

The decision depends on where you want complexity and what your product prioritizes. Let's reason from the requirements we already have:

- We already run a collaboration service in the middle of every edit.

- We want clients to stay lightweight.

- Offline-first is not a core requirement in our scope.

Our Choice: With a centralized collaboration service and online-first workflow, OT fits better. It keeps client logic lighter and uses the ordering point we already operate. If offline-first becomes a primary requirement, CRDTs become more attractive despite their complexity.

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

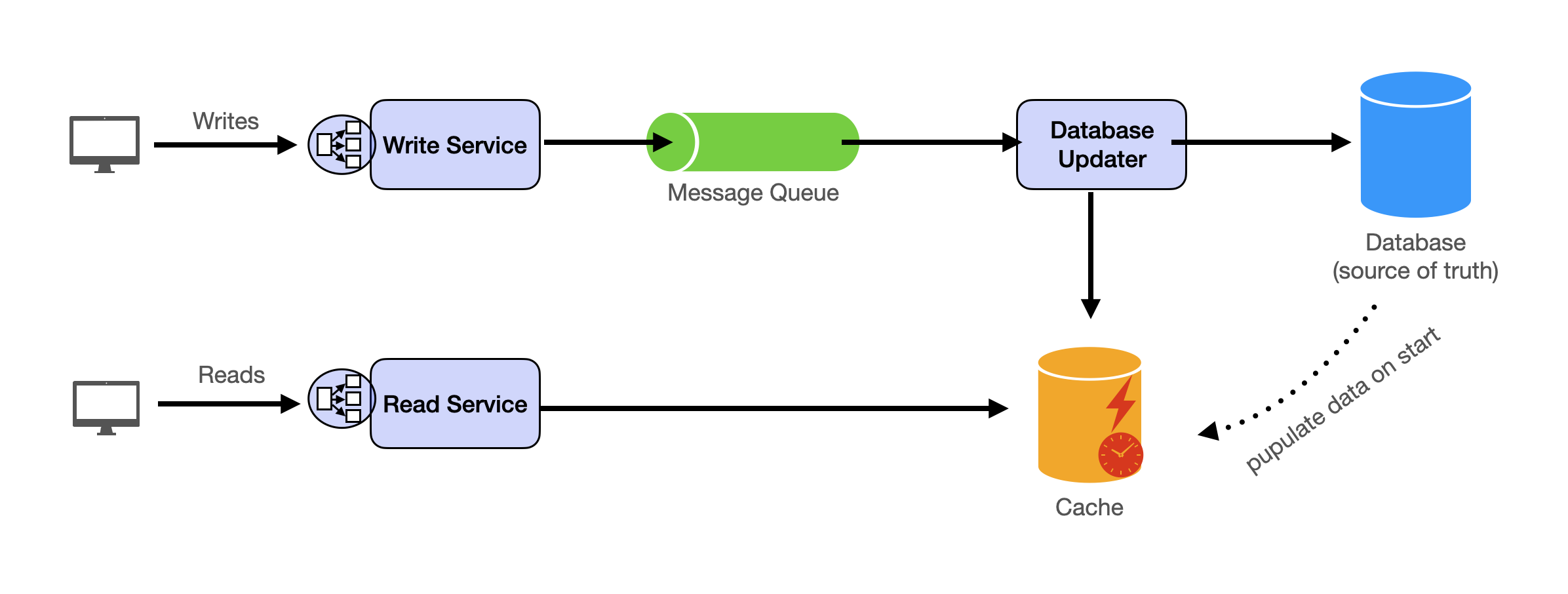

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.