A typeahead system, often called autocomplete, is a feature in software programs that predicts the rest of a word or phrase that a user is typing. This functionality helps users to find and select from a pre-populated list of values as they type, reducing the amount of typing needed and making the input process faster and more efficient.

An everyday example of a typeahead system is Google's search box. As you begin typing your search query, Google provides a dropdown list of suggested search terms that match what you have typed so far. These suggestions are based on popular searches and the content indexed by Google's search engine. This allows you to see and select your intended search without having to type out the entire term, making the search process faster and more efficient.

When a user begins to type in the search box, the typeahead feature could suggest book titles, authors, or genres that match the typed characters. For instance, if the user types in "Har", the system could suggest "Harry Potter", "Harper Lee", etc. This kind of typeahead system can greatly enhance the user experience by providing instant feedback and helping users to formulate their search queries.

The search ranking is based on frequency of user inputs, updated daily. For example, if "Harry Potter" is searched 10 times and "Harper Lee" is searched 5 times, "Harp Lessons" is searched 2 times in the last 24 hours, then they should be ranked in that order.

In this problem, we will design a typeahead system for a large e-commerce site. The system will provide search suggestions to users as they type in the search box. The suggestions will be based on the most popular searches and the content indexed by the e-commerce site's search engine.

Functional Requirements

- The system should return search suggestions as the user types in the search box.

- The system should return top 10 results for each query.

- The system should prioritize more relevant suggestions (e.g., based on popularity or other relevance metrics).

- The system should handle updates to the data, e.g., new entries added.

- Use a Trie to store the data.

Nonfunctional Requirements

Scale requirements:

- 100 million daily active users

- Each user makes 20 queries a day

- Search data should be updated daily

Other requirements:

- Availability: The system should be highly available and aim for near-zero downtime. The system should have error handling mechanisms to prevent crashes and ensure it can handle large amounts of traffic.

- Scalability: The system should support 100 million daily users.

- Latency: The system should provide search suggestions in real-time (within a few hundred milliseconds).

- Efficiency: The system should efficiently use memory and computational resources.

- Consistency: Since the system will be read-only for the clients, consistency is not a primary concern.

Resource Estimation

Assumptions:

- DAU (Daily Active Users): 100 Million

- Average search queries/user/day: 20

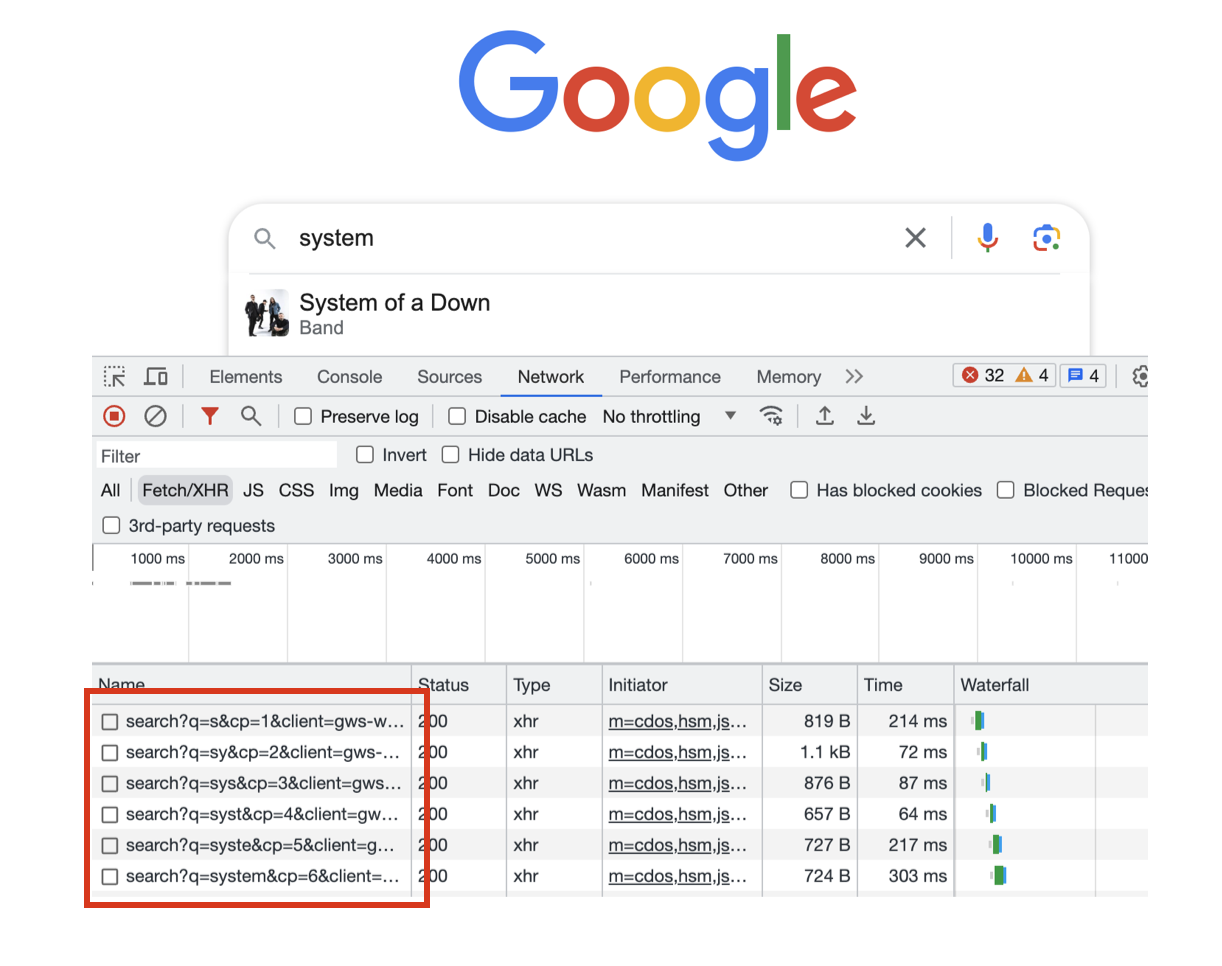

It's worth noting that a new request is made every time a user types in a new character. We can see this by checking out Google's requests in Chrome Devtool's network tab:

Assuming the average number of characters of a query is 10, then the number of requests per query is 10 * average searches daily per user of 20 = 200 queries/user/day.

Estimations:

Read:

- QPS (Queries per second): 100M users * 200 queries / user / (24 * 3600) seconds = ~230k queries/sec.

- Assume 2x peak traffic, peak QPS is 230k *2 = 460k queries/sec.

Write:

Assume 10% of the queries are new, each query is 10 character and each character is 2 bytes, then each query adds 20 bytes. This 100MM * 200 queries * 10% * 20 bytes = 40GB. For a year, it's 14,600 GB = 14.6TB, a large but managable amount of storage.

Use the resource estimator to calculate.

Performance Bottleneck

Given these numbers, the bottlenecks are likely to be in handling QPS and retrieval speed for providing suggestions in real-time.

API Design

Our system can expose the following REST APIs:

GET /suggestions?q={search-term}

Response should include a list of suggested terms, ordered by relevance:

{

"suggestions": ["suggestion1", "suggestion2", ..., "suggestionn"]

}

High-Level Design

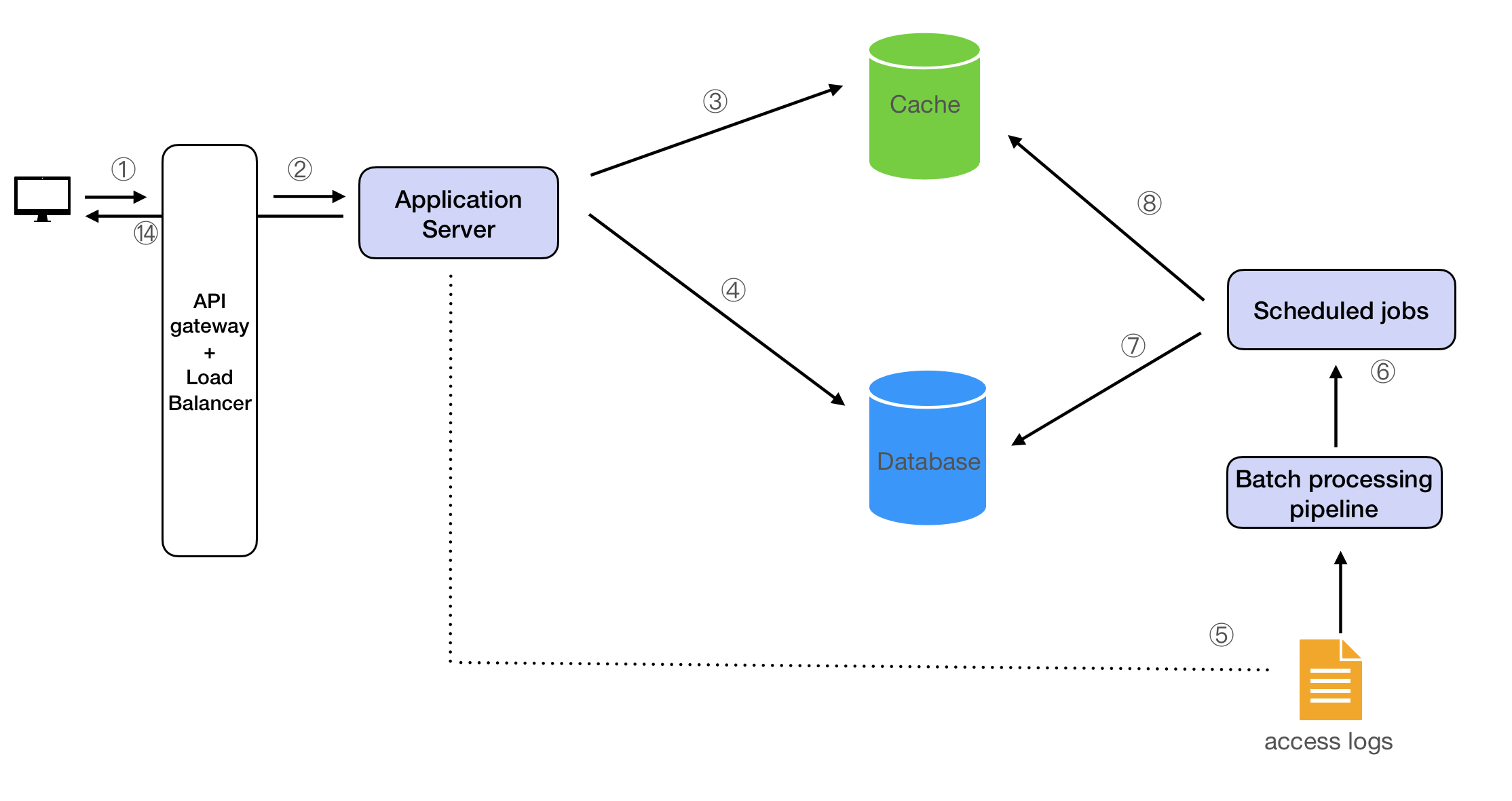

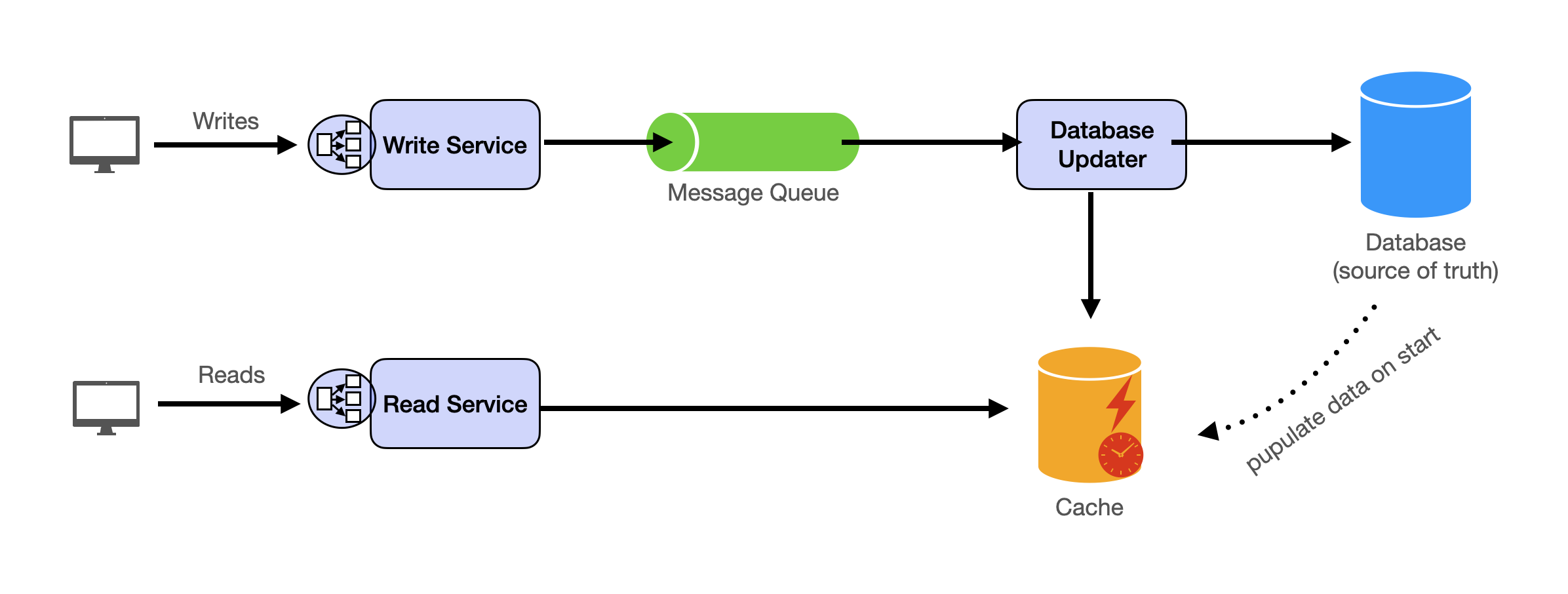

Read Path

- The client sends an HTTP request to the

GET /suggestionsinterface to start a query; - The load balancer distributes the request to a specific application server;

- The application server queries the index stored in the cache;

- The application server queries the database if data satisfying the query is not found in the cache;

Write Path

- Access log from the application servers are aggregated.

-

-

- Scheduled jobs kick off batch processing pipelines that read the logs and use the aggregated data to update the index in the database and the cache.

-

Detailed Design

How to Implement the Index?

Approach 1: Using a Trie

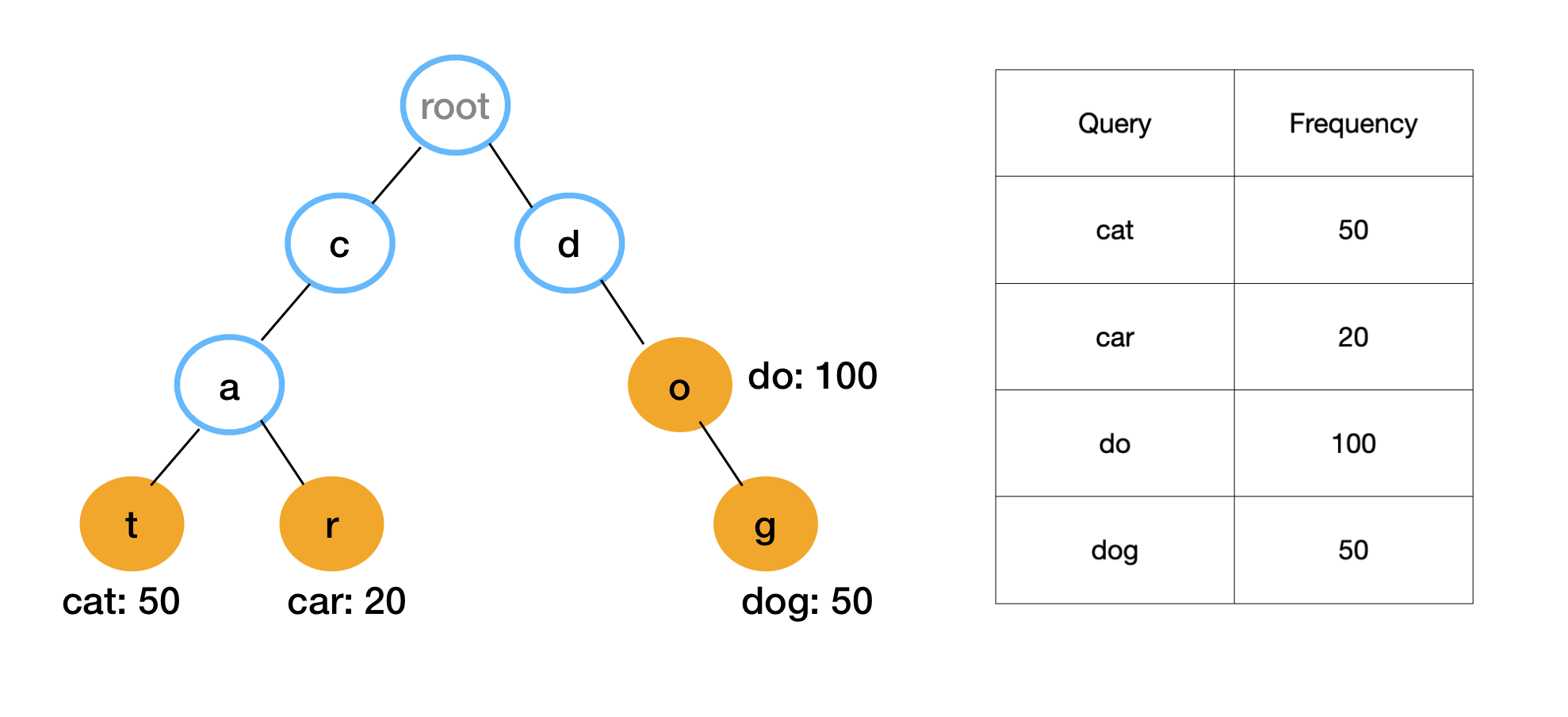

A Trie (or Prefix Tree) is a tree-like data structure that is used to store a dynamic set or associative array where the keys are usually strings. All the descendants of a node have a common prefix of the string associated with that node, and the root is associated with the empty string. Feel free to learn more about trie from a data structure perspective.

In the context of the typeahead system, each node in the Trie could represent a character of a word. So, a path from the root to a node gives us a word in the dictionary. The end of a word is marked by an end of word flag, letting us know that a path from the root to this node corresponds to a complete, valid word. The time complexity to get to a node is liner to the length of the prefix.

The frequency of the words are stored in the node themselves. To find the top results, we can find all the nodes in the subtree and sort them by the frequency.

Approach 2: Using Inverted Indexes with Edge N-grams

An inverted index is a data structure used to create a full-text search. Traditionally, an inverted index maps terms to documents containing those terms. Search engines like Elasticsearch adapt this for typeahead using edge n-grams.

Edge n-gram tokenization breaks each word into all its prefixes. For typeahead, we treat each search term as a "document" and its prefixes as the indexed "terms". When a word like "car" is indexed, Elasticsearch generates edge n-grams: "c", "ca", "car". The inverted index then maps each prefix to the words containing it.

Here is how the inverted index structure looks:

{

"c": ["car", "cat"],

"ca": ["car", "cat"],

"car": ["car"],

"cat": ["cat"],

"d": ["dog"],

"do": ["dog"],

"dog": ["dog"]

}

Each prefix (the indexed term) maps to the complete words (the "documents") that start with that prefix.

When searching for the prefix "ca", the system looks up "ca" in the index and retrieves the associated words: ["car", "cat"]. This is exactly how Elasticsearch implements autocomplete functionality.

As you can see, the Trie and the Inverted Index provide the same results, but they store the data in different ways and the search operations work differently.

Approach 3: Using Predictive Machine Learning Models

Predictive models use machine learning algorithms to predict future outcomes based on historical data. In the context of the typeahead system, we could use a predictive model to suggest the most likely completions of a given prefix, based on the popularity of different completions in the past. This predictive nature is fundamentally how popular tools like ChatGPT work.

This approach could give us more relevant suggestions, but it would be more complex to implement and maintain. Moreover, the suggestions would only be as good as the quality and quantity of the historical data.

In this article, we will use the simple Trie approach in our design. As we will see in the detailed design, the optimized data storage is similar to inverted index.

How to Use a Trie to Implement Typeahead

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.