Introduction

A rate limiter controls how many requests a user, API key, or IP address can make in a given time window.

Stripe allows "100 requests per second per API key." If a client sends 150 requests in one second, the rate limiter allows the first 100 and returns 429 Too Many Requests for the remaining 50. This protects Stripe's backend from overload while giving each customer a fair share of capacity.

You'll find rate limiters in every public API (Twitter, GitHub, AWS), multi-tenant SaaS platforms, and any system that needs to prevent abuse or ensure fair resource sharing.

Background

The question was intentionally vague as is often the case in system design interviews. We want a rate limiter to protect backend services—but where do we put it?

Why Throttle Early

The core goal is protecting your backend from overload. If we check limits after a request reaches backend services, we've already paid the cost: database queries, business logic, downstream service calls. A throttled request should consume minimal resources. This means we need to enforce limits before any expensive work happens.

Where the Limiter Sits

Since where enforcement happens cascades into every other part of the system, let's tackle it first to set the stage for the rest of the design.

We need to enforce "100 requests per second per user" before the backend does any expensive work. But where in the request path should we check this limit? Let's reason through the options by thinking about when we can identify the user and when we can reject the request.

Our Choice: Gateway/Edge Placement

We're going to choose gateway placement for this design. Here's why: the problem statement asks for "consistent global limits" across a distributed system. Gateway placement is the only option that gives us a single enforcement point without adding extra network hops. While a dedicated service would also work, it adds 1-5ms of latency on every request—that's 10-50% of our entire latency budget when we're targeting single-digit millisecond overhead.

The tradeoff is that the gateway becomes a critical dependency, but we mitigate that with multiple gateway instances (which we'd need anyway for scale). This matches production patterns you'll see at companies like Stripe, Twilio, and AWS API Gateway.

Functional Requirements

-

The rate limiter must run inline at the API gateway to block excess traffic before it reaches backend services.

-

The gateway must call a limiter module and react correctly on allow vs deny, including returning proper HTTP responses to the client.

-

The system must determine a stable identity per request (user, API key, tenant, IP) to track usage fairly and prevent abuse.

-

The limiter must allow short bursts of requests while enforcing a long-term average rate per identity.

-

The limiter must enforce limits correctly across multiple API gateway instances, so traffic cannot bypass limits by hitting different instances.

-

Operators must be able to update rate limit policies safely without redeploying gateways.

Scale Requirements

- 1 million requests per second (think: medium-sized API like Stripe, Twilio)

- 100 million different users/API keys (each gets their own rate limit bucket)

- Rate limiter must add less than 10ms to each request

- Unused rate limit data should automatically delete itself (don't store limits for users who stopped making requests months ago)

Non-Functional Requirements

The scale requirements translate to these system qualities:

Scale

- Handle 1 million requests per second at the gateway

- Support millions of different users/API keys without running out of memory

Latency

- Add less than 10ms per request for rate limit checks

Availability

- Keep the API running even if the rate limiter has problems

- Decide what happens when dependencies fail (allow all requests vs block all requests)

Correctness

- When two requests for the same user arrive at the same time, both checks must see the current token count (if we allow one request to read stale data, we might allow 101 requests when the limit is 100)

- Prevent users from bypassing limits by sending requests to different gateways at once

Security

- Make sure users can't fake their identity to get more quota (e.g., changing their API key in the header to look like a different user and reset their rate limit counter)

High Level Design

1. Gateway Placement with Inline Filter

The rate limiter must run inline at the API gateway to block excess traffic before it reaches backend services.

From the background section, we chose gateway placement. Now let's make that concrete.

The Filter Approach

We run the rate limiter as a filter inside the API gateway—a piece of code that intercepts every request before it goes anywhere else. When a request arrives, the filter checks "has this user exceeded their limit?" If yes, return 429 immediately. If no, let the request through to the backend.

The gateway already extracts the API key for authentication. The rate limit filter reuses that identity to look up current usage. Since we're inline, denied requests never touch the backend—they cost only the limit check itself (a Redis call, typically 1-2ms).

What This Creates

The limiter now sits on the hot path for every request. This creates two constraints we need to solve:

- Speed - We have a 10ms latency budget. The limit check must be fast.

- Correctness - Multiple gateways might check the same user simultaneously. We can't let race conditions cause over-admission.

The remaining requirements address these constraints. FR2-4 define what the filter does. FR5 solves the multi-gateway coordination problem.

Two Components

It helps to think of the rate limiter as two separate pieces:

The RateLimit Filter runs in the gateway. It extracts identity, looks up the policy, calls the state store, and decides allow/deny. This is the decision logic.

The state store holds the counters (how many tokens does this user have?). In a single-gateway setup, this could be in-memory. In production with multiple gateways, it must be shared—we'll use Redis. We will cover this more in the following sections.

2. Gateway-Limiter Interface

The gateway must call a limiter module and react correctly on allow vs deny, including returning proper HTTP responses to the client.

The gateway filter needs to ask one question: "Should I allow this request?" The limiter answers with three pieces of information: yes/no, how long to wait if denied, and how many requests remain in the quota.

The Check

For each request, the gateway passes the limiter three things: who's making the request (API key or user ID), which endpoint they're hitting (/api/search), and the policy that applies (10 requests per second, 20 token capacity). The limiter checks current usage against the policy and returns a decision.

If allowed, the gateway forwards the request to backend services. If denied, it returns an error immediately—no backend work happens.

The 429 Response

When denying a request, the gateway returns HTTP status 429 Too Many Requests. This status code is universally recognized by HTTP client libraries—most will automatically back off and retry.

The response also includes a Retry-After header with the number of seconds until the client can retry. Without this, 1000 throttled clients would all retry immediately, creating a thundering herd. With Retry-After: 5, they spread their retries over time.

3. Identify the Requestor

The system must determine a stable identity per request (user, API key, tenant, IP) to track usage fairly and prevent abuse.

Before we can enforce "10 requests per second," we need to define what "per" means. Per user? Per API key? Per IP address?

Extracting Identity

The gateway already parses the X-API-Key header or Authorization: Bearer <token> for authentication. We reuse this to identify who's making the request. From the authenticated context, we can also derive the tenant/organization (which maps to billing plans) and extract the IP address from headers or the direct connection.

Why Multiple Scopes

We don't pick one identity—we extract all of them and enforce limits at each scope simultaneously. A request must pass per-API-key, per-IP, and per-tenant checks. If any fails, deny.

Why layer them? Each scope catches different abuse patterns. Per-API-key ensures fairness (each customer gets the same limit). Per-IP blocks Sybil attacks—an attacker who creates 100 free accounts still comes from the same IP and hits the per-IP limit. Per-tenant prevents a runaway script from one user exhausting an entire organization's quota.

The expandable section explains each scope's tradeoffs. For implementation details on how Redis keys and rules work together for multiple scopes, see [#keys-and-rules].

4. Burst-Tolerant Algorithm

The limiter must allow short bursts of requests while enforcing a long-term average rate per identity.

Why Bursts Happen

A user loads a dashboard page. The page makes 20 API calls in parallel for different widgets. A strict "10 requests per second" limiter allows 10, denies 10. The page loads half-broken. But this user is well-behaved—over the next minute, they sent only 20 requests total (0.33 req/sec average). The strict enforcement punished a normal traffic pattern.

We need an algorithm that allows bursts while enforcing long-term average. Let's look at the options.

Our Choice: Token Bucket

Token bucket gives users a "savings account" of requests. Tokens accumulate over time (the refill rate), up to a maximum balance (the capacity). Each request withdraws one token. If the account is empty, the request is denied.

Back to our dashboard example: the user was idle for 2 seconds, accumulating 20 tokens (10/sec × 2 sec). When the page loads and fires 20 parallel requests, the bucket has enough tokens. All 20 pass. The user's long-term average is still well under the limit.

The algorithm needs just two values per user: current token balance and the timestamp of the last refill. When a request arrives, calculate how much time has passed, add the appropriate tokens (capped at capacity), then check if there's enough to allow the request. This is 16 bytes of state and constant-time math—far cheaper than sliding window's timestamp log.

When denying a request, we can calculate exactly when enough tokens will refill. If the user has 0.3 tokens and needs 1, and tokens refill at 10/second, they'll have enough in 0.07 seconds. Round up to 1 second for the Retry-After header. This tells clients exactly when to retry instead of hammering the API.

Storing Token Bucket State

The algorithm needs to persist two values per user: current token count and last refill timestamp. On each request, you calculate elapsed time, refill tokens proportionally, check availability, and update the state.

Redis works well for this. It's an in-memory key-value store with sub-millisecond latency. Store the user's token state under a key like ratelimit:user:123:tokens. Redis handles millions of reads and writes per second, and its TTL feature automatically expires inactive user keys after a timeout (e.g., 1 hour).

The basic flow: read the key, calculate new token count based on elapsed time, check if sufficient tokens exist, decrement if allowing the request, write back the updated state. The next sections cover how this works across multiple gateway instances and how to prevent race conditions.

5. Consistent Enforcement Across Gateways

The limiter must enforce limits correctly across multiple API gateway instances, so traffic cannot bypass limits by hitting different instances.

The Multi-Gateway Problem

In production, you run 10-100 gateway instances for availability and scale. If each gateway tracks limits in its own memory, a user can hit all 10 gateways and get 10× their limit. A policy of "10 req/sec per user" becomes "10 req/sec per user per gateway" = 100 requests per second total.

Shared State with Redis

The solution: all gateways read and write token counts from a shared store. When Gateway A allows a request and decrements the token count, Gateway B sees that update immediately.

Redis fits this role well. It's an in-memory key-value store with sub-millisecond latency (typically 0.2-1ms per operation). It supports Lua scripts for atomic read-modify-write operations—critical for preventing race conditions when multiple gateways check the same key simultaneously. And it has built-in TTL support, so inactive users' keys automatically expire instead of consuming memory forever.

Each rate limit key combines identity and scope: ratelimit:ak_abc123:/api/search. If enforcing multiple scopes (per-user + per-IP + per-tenant), create separate keys and check all of them. Deny if any fails.

Atomic Updates

Two gateways might check the same key at the same instant. If both read "5 tokens," both think they can allow a request, and both write "4 tokens." The user got two requests through but only paid for one token. This is a race condition.

Redis solves this with Lua scripts. The gateway sends a script that reads the current tokens, calculates the new value, and writes it back—all as a single atomic operation. No other command can run in the middle. The Deep Dive section covers the implementation.

When Redis Fails

Redis is now on the critical path. If it's slow or down, set an aggressive timeout (10ms) so a slow Redis doesn't cascade into slow API responses. Most production systems fail-open (allow all requests) during outages to maintain API availability, with local in-memory limits as a coarse fallback. The Deep Dive explores failure modes in detail.

6. Policy/Config Management

Operators must be able to update rate limit policies safely without redeploying gateways.

An attacker starts hammering your login endpoint. You need to tighten the limit from 100/minute to 10/minute—right now. If policies are baked into gateway config files, you're looking at a rolling restart across all instances. That takes too long. Policies must update without restarts.

Adding Policy Components

We need two new components in our architecture:

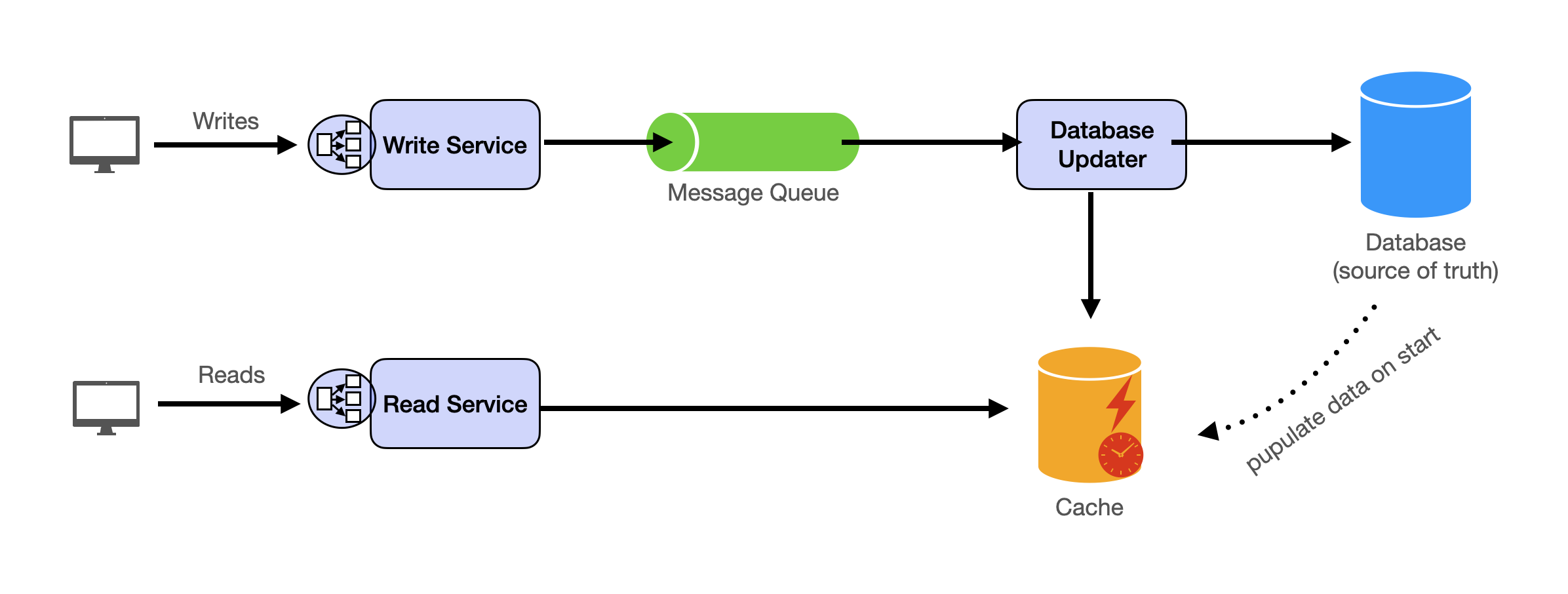

A Policy Store (database or config service) holds all rate limit rules: which endpoints they apply to, which identity scope to track, and the token bucket parameters. This is the source of truth that operators update.

A Policy Service sits between the store and gateways. When a policy changes, it notifies gateways to refresh their cache. Gateways cache policies in memory so the hot path never calls the policy service per-request.

The Deep Dive section covers distribution strategies (push vs pull), dry-run mode for testing new policies safely, and handling exceptions for enterprise customers with custom limits.

Deep Dive Questions

How do you ensure consistent rate limiting across multiple gateway instances?

You have 10 gateway instances behind a load balancer. A user with a 100 requests/minute limit sends 200 requests. The load balancer distributes them evenly—20 requests to each gateway. If each gateway tracks limits independently, each sees only 20 requests and allows them all. The user just got 200 requests through—double their limit.

This is the distributed enforcement problem. Local counting doesn't work when traffic spreads across instances.

Why Shared State

All gateways need to read and write the same counters. When Gateway A allows a request and decrements the token count, Gateway B must see that updated count immediately. This points to a shared data store.

The store needs three properties:

-

Fast reads and writes - We're checking limits on every API request. Adding 50ms of latency is unacceptable. We need sub-millisecond operations.

-

Atomic updates - Two gateways might check the same key simultaneously. The store must handle this without race conditions (covered in the next deep dive).

-

Auto-expiration - Users come and go. If someone stops making requests, their rate limit state should eventually disappear. We can't store counters forever.

Redis fits all three: in-memory storage gives sub-millisecond latency, Lua scripts provide atomicity, and TTL (time-to-live) handles expiration automatically. A traditional SQL database would struggle with millions of writes per second. A distributed cache like Memcached lacks the atomic scripting we need.

Living with the Latency

Redis adds 1-2ms to every request. For most APIs, this is acceptable—your backend probably takes 50-200ms anyway. But it's not free.

Minimize overhead with connection pooling (reuse connections instead of opening new ones) and pipelining (batch multiple Redis commands into one network round trip when checking multiple rules).

The Availability Tradeoff

Redis is now on your critical path. If Redis goes down, what happens to your API? This is covered in detail in the Failure Handling deep dive, but the short answer: set aggressive timeouts (10ms), use a circuit breaker to stop calling Redis when it's unhealthy, and fall back to local in-memory limits as a safety net.

Alternative: Local State with Sync

Some systems skip shared state entirely. Each gateway maintains local counters and periodically syncs with a central store. This trades accuracy for independence—if the central store goes down, gateways keep working with local limits.

The tradeoff: limits can be exceeded by up to num_gateways × local_limit during the sync interval. With 10 gateways and a 100/minute limit, a user could theoretically get 1000 requests through before the sync catches up. This is only acceptable for coarse limits where overage doesn't matter much (e.g., "10,000 requests per day" where occasional bursts are fine).

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.