Introduction

System design knowledge matters for two reasons. First, companies test it in interviews, especially at senior levels. Second, it separates competent engineers from exceptional ones. Writing code is table stakes. Designing robust, scalable systems requires deeper expertise.

What Is System Design?

System design is the process of defining the architecture, components, modules, interfaces, and data for a system to satisfy specified requirements. It is essentially creating a blueprint for a complex software system to ensure it is efficient, reliable, and scalable.

System design is the art of making technical trade-offs to turn a vague problem into a scalable solution. It is not just about connecting boxes; it is about justifying why you connected them that way based on constraints.

System Design vs Object-Oriented Design

System design interviews differ fundamentally from object-oriented design.

| Aspect | Object-Oriented Design | System Design |

|---|---|---|

| Example Problems | Design a parking lot, elevator controller, chess game, vending machine | Design Twitter, YouTube, Uber, Netflix |

| Scale | Single machine | Large scale, millions of users, petabytes of data, multiple data centers |

| Focus | Code structure, class relationships, design patterns | Architecture, distributed systems, scalability |

| Skills Tested | Class design, inheritance, interfaces, SOLID principles | Component selection, data flow, partitioning, replication, trade-offs |

| Output | UML diagrams, code implementation, class hierarchies | Architecture diagrams, capacity estimates, API design, database schemas |

| Execution | Code runs on single process | Services span multiple servers and regions |

The skills overlap but the emphasis differs. Object-oriented design emphasizes clean code and maintainability. System design emphasizes performance, reliability, and cost at scale.

What Are System Design Interviews?

Writing code becomes less central as careers progress. Companies need engineers who design systems that handle high traffic, make decisions balancing cost and performance, and lead technical discussions. System design interviews assess these capabilities.

These interviews appear at mid-level and becomes central to senior positions. At senior levels, engineers contribute to application architecture and make design choices affecting entire systems. Interviews simulate real-world scenarios involving scalability, fault tolerance, and performance.

System design takes years to master. Real systems require thousands of hours of work. Demonstrating competence in 45 minutes presents a unique challenge.

What System Design Interviews Test

System design interviews test soft skills more than raw knowledge. Can you break down vague, open-ended problems into solvable parts? Do you understand how components interact? Can you design scalable, reliable, maintainable systems?

Every design decision has trade-offs. Explain why you chose one approach over another. Communication matters as much as technical depth. Clear explanations are essential for collaborating with teams and stakeholders in real settings. System design rarely follows a straight path. Adjust your approach based on new constraints or feedback.

Level Expectations

Interview expectations change dramatically with seniority. Understanding what your level requires prevents wasted preparation.

The single biggest difference between levels is the ability to handle ambiguity. Junior engineers receive well-defined problems with clear requirements. Senior engineers face deliberately vague problems requiring clarification and decomposition. Staff engineers navigate extreme ambiguity, defining the problem space itself.

This manifests in problem complexity. L4 problems have simple contracts: given input A, return output B. L5 problems combine 2-3 concepts with some flexibility. L6 problems either combine 4-5 subsystems or present abstract requirements needing significant clarification before design begins.

| Level | Problem Scope | Depth Expected | Common Topics | Interview Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L3-L4 (Junior/Mid) | Well-defined problems with guidance | Surface-level understanding | Basic components: cache, database, load balancer, API design | Template execution, component knowledge, basic trade-offs |

| L5 (Senior SWE) | Clearer requirements, some ambiguity | Moderate depth on 1-2 components | Scaling patterns, database partitioning, caching strategies, message queues | Architecture choices, explaining trade-offs, handling common scale challenges |

| L6 (Staff SWE) | Ambiguous requirements, must clarify scope | Deep dive on 2-3 components | Distributed systems, consistency models, replication, consensus, failure handling | Navigating ambiguity, deep technical knowledge, production considerations |

The depth of technical understanding also progresses distinctly. For example,

- L4: What is strong consistency? (Concept awareness)

- L5: How do we implement strong consistency? (Implementation knowledge)

- L6: Why this consistency implementation over alternatives, and more importantly, why strong consistency instead of eventual consistency for this use case? (Trade-off justification and requirements mapping)

How Companies Differ

Interview formats, leveling systems, and expectations vary significantly across companies. Understanding these differences helps you prepare appropriately and set realistic expectations.

Leveling Systems and Progression

| Company | Entry Level | Mid Level | Senior Level | Staff+ | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L3 | L4 | L5 | L6-L8 | Slow progression, high bar for senior+ levels. L5 is terminal level for most. Expect 3-5 years between levels. | |

| Meta | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6-E9 | Faster progression than Google. E5 achievable in 2-3 years. Performance-driven culture. |

| Amazon | SDE I | SDE II | SDE III (Senior) | Principal+ | Faster initial progression. Strong emphasis on leadership principles. L6+ requires scope beyond code. |

| Microsoft | 59-60 | 61-62 | 63-64 (Senior) | 65+ (Principal) | Slower progression. System design starts at 62+. Emphasis on cross-team collaboration. |

| Apple | ICT2 | ICT3 | ICT4 | ICT5+ | Secretive leveling. Very slow progression. Product-focused, less emphasis on pure scale. |

Titles at Junior and Mid-levels are roughly equivalent across companies, but diverge sharply at Senior levels. Google and Meta represent opposite extremes: Google favors slow, tenure-heavy progression (L5-L6 take years), while Meta rewards rapid impact (E6 achievable in 5-7 years). Google L4 is considered a terminal level for many engineers, while Meta's terminal level is E5. Amazon has the "SDE II Trap" where jumping from L5 to Senior requires cross-team scope equivalent to Staff elsewhere. Microsoft offers steady climbs until the "Principal Cliff" at Level 65, where roles shift from engineering to business strategy with rare slots. Apple is known for being design-driven and engineering promotion is rigid—you cannot "create" scope like at Meta or Google but must wait to be assigned larger projects, making progression heavily tenure and business-dependent.

L4: Mid-Level

L4 problems have simple contracts. TinyURL takes a long URL and returns a short one. YouTube view counter takes a video ID and returns a count. These are solved problems with standard solutions.

The interview is mechanical. Clarify requirements (5 minutes), design APIs (5 minutes), draw architecture (15 minutes), light deep dive (15 minutes). Since the solution is known, interviewers have low tolerance for messy structure. You must own the template.

You need to know the basic building blocks: load balancer, cache, database, message queue. When to use SQL versus NoSQL. Vertical versus horizontal scaling. That's it.

Deep dives stay surface-level. "How does cache eviction work?" Answer: "LRU removes least recently used items." You don't need code-level implementation details.

Most candidates fail from poor time management. They run out of time or present disorganized designs. Not from lacking knowledge.

L5: Senior Engineer

L5 problems scale a specific feature. Top K songs combines counting and ranking. Flash sales need distributed counters with consistency. News feed sits on the L5/L6 boundary—at L5 you focus on fan-out (push versus pull) and basic storage. At L6 it becomes complex ranking and ad blending.

The interview has moderate ambiguity. You must ask about scale and constraints proactively. The mental shift is from "How do I build a component?" to "How do I scale this feature without breaking?"

You should identify bottlenecks without prompting. "The database write speed is the limit here." Then explain how to fix it.

You need to know how scaling patterns actually work. "How do you partition the database?" Answer with specifics: "Hash-based partitioning on user_id ensures even distribution." Then explain trade-offs when pushed: "It avoids hotspots, but resizing the cluster is painful."

Deep dives go deeper. Spend 20 minutes explaining 1-2 components in detail. The challenge is balancing breadth (covering the full design) with depth (proving you understand the hardest bottlenecks).

L6: Staff Engineer

L6 problems are either highly ambiguous or infrastructure-level. Design a distributed job scheduler. Design an ad-serving system. These aren't features—they're the operating system other engineers build on. They require strict guarantees: exactly-once delivery, ordered processing, no data loss.

The interview has no template. You lead. Aggressively manage time to focus on complexity. Skip boring parts fast: "Standard load balancer and SQL for user auth, let's move on." Buy time for novel problems.

Identify what's actually hard. "The hard part isn't storage. It's preventing two workers from grabbing the same job when the network is slow." Focus there.

You need to understand guarantees and failure modes deeply. Not textbook definitions—practical reality. "A worker crashed after processing a payment but before sending the success signal. The scheduler retries. Now you charged the user twice. How do you solve this? Fencing tokens? Database constraints? Leases?"

The interviewer probes every decision. "Why strong consistency over eventual?" You must tie answers to business impact. "What if requirements change to prioritize availability?" Your job is defending trade-offs under changing constraints.

How to Prepare

The Memorization Trap

The prevailing approach is: find popular system design problems, watch YouTube videos showing solutions, read blog posts with architectural diagrams, memorize the answers, repeat.

This works at first. You watch a video explain how to design Twitter. The solution makes sense: microservices, message queues, Redis cache, Cassandra database. You memorize the architecture. In your interview, you get asked to design Twitter. You draw the diagram from memory.

The strategy may work but as more and more interviewers recognize the cookie-cutter answers, the strategy fails.

First, you freeze when facing unfamiliar problems. You memorized 30 solutions. The interviewer asks you to design something you haven't seen. You try adapting your Twitter design to fit. It doesn't work cleanly. You stumble. The interviewer notices.

Second, interviewers recognize memorized answers. Hundreds of candidates have watched the same videos and read the same blog posts. When your Twitter design matches the popular YouTube solution exactly, the interviewer's instincts activate. They probe deeper. You can't answer because you memorized the what, not the why. For L5+ interviews, the cookie-cutter answers may only be enough talking points for the first 15-20min, the interviewer will probe deeper and deeper until they find the edge of your knowledge.

Third, the approach completely fails at L6+. Senior interviews require deep understanding. These interviews are mostly about deep dives It would become obvious whether you have actual experience or not. The interviewer asks follow-up questions until they find the edge of your knowledge. Memorized facts crumble quickly under pressure.

The Better Approach

Learn the fundamentals. Understand how things actually work. Build genuine technical depth.

For L4-L5 engineers with limited time, the hybrid approach works best. Master the common patterns and the templates. Study 10-15 common problems to internalize the template. But for each problem, don't just memorize the solution. Understand why each component exists. Question every design choice. What happens if we remove the cache? Why Cassandra instead of PostgreSQL? Why Redis over Memcached?

This deeper engagement transforms memorization into understanding. When you face unfamiliar problems, you recognize patterns. You adapt rather than freeze.

Why System Design School Exists

System Design School takes the fundamentals-first approach. You won't find memorizable Twitter solutions. You'll find building blocks for constructing any solution.

This primer provides a quick crash course: essential components, interview templates, and the mental models needed to solve common problems. It's designed for rapid learning and last-minute preparation.

The full course goes deep. It's organized into two main tracks:

Fundamentals covers the core building blocks that appear in every system design interview:

- Microservices & Communication: How services talk to each other. Message queues, Kafka, circuit breakers, service discovery. Why async communication prevents cascading failures.

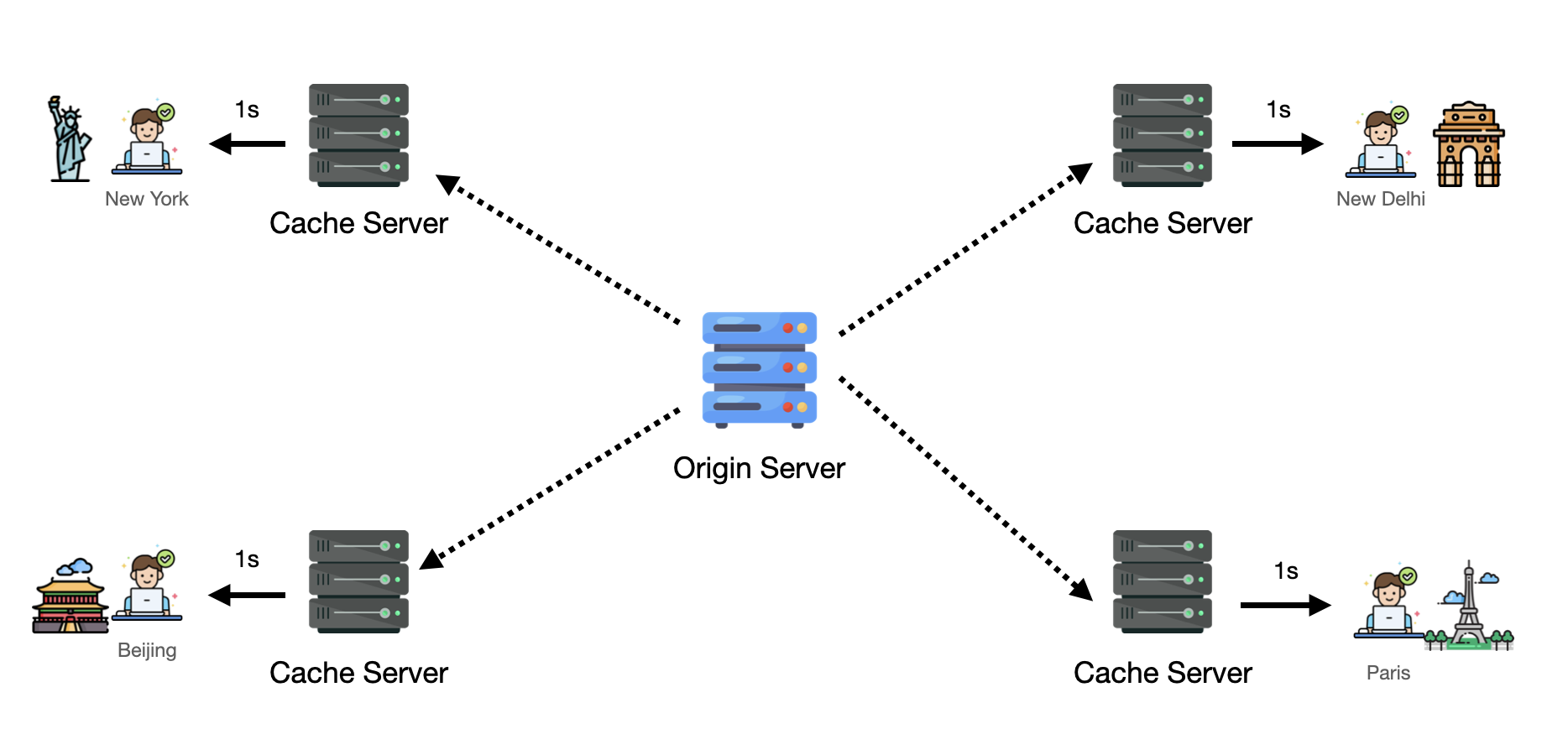

- Scaling Services: Load balancing, auto-scaling, caching patterns, CDNs. When to use cache-aside versus write-through. How to handle cache thundering herd.

- Data Storage: B-trees, LSM trees, SQL versus NoSQL. When to use document databases versus key-value stores. OLTP versus OLAP workloads.

- Scaling Data: Replication (primary-replica, multi-leader), partitioning (consistent hashing, range-based), change data capture. How to handle partition rebalancing.

- Batch & Stream Processing: MapReduce, stream processing, lambda architecture. When to use batch versus stream.

- Patterns: Rate limiting, unique ID generation, saga pattern, fan-out/fan-in. Reusable solutions to common problems.

Domain Knowledge covers specialized topics that appear in specific problem types:

- Transactions: Database isolation levels, pessimistic versus optimistic locking, flash sale inventory patterns. How to prevent double-booking.

- Distributed Systems: CAP theorem, PACELC theorem, consistency models, consensus algorithms (Raft, Paxos), failure handling. The theory behind the practice.

- Geospatial Search: Geohash, quadtrees, H3 hexagonal indexing, S2 library. How Uber finds nearby drivers.

- Search Engines: Inverted indexes, TF-IDF, BM25, Elasticsearch architecture. How search actually works.

- Media Systems: Video transcoding, file chunking, adaptive bitrate streaming. How Netflix delivers video.

- Probabilistic Data Structures: Bloom filters, count-min sketch, HyperLogLog. Memory-efficient approximations for massive scale.

For L4-L5, the primer gets you interview-ready fast. The full course adds depth. For L6+, you need the full course—surface knowledge fails under aggressive probing.

Where to Start

This primer follows a logical progression. First, understand system design concepts. Then learn the interview framework.

Interviewing tomorrow? See the System Design Master Template for the pattern that solves most problems.

Want core concepts quickly? Review Understanding Core Design Challenges and How to Scale a System.

New to system design? Start with the main components section.

Familiar with components but need interview structure? Check the step-by-step interview walkthrough.

Core Design Challenges

Now that we understand how to solve system design problems, examine the most common challenges. Like solutions assembled from reusable building blocks, these challenges have repeatable patterns.

Challenge 1: Too Many Concurrent Users

Large user bases introduce many problems. The most common and intuitive is that single machines or databases have RPS/QPS limits. In all single-server demo apps from web dev tutorials, server performance degenerates fast once limits are exceeded.

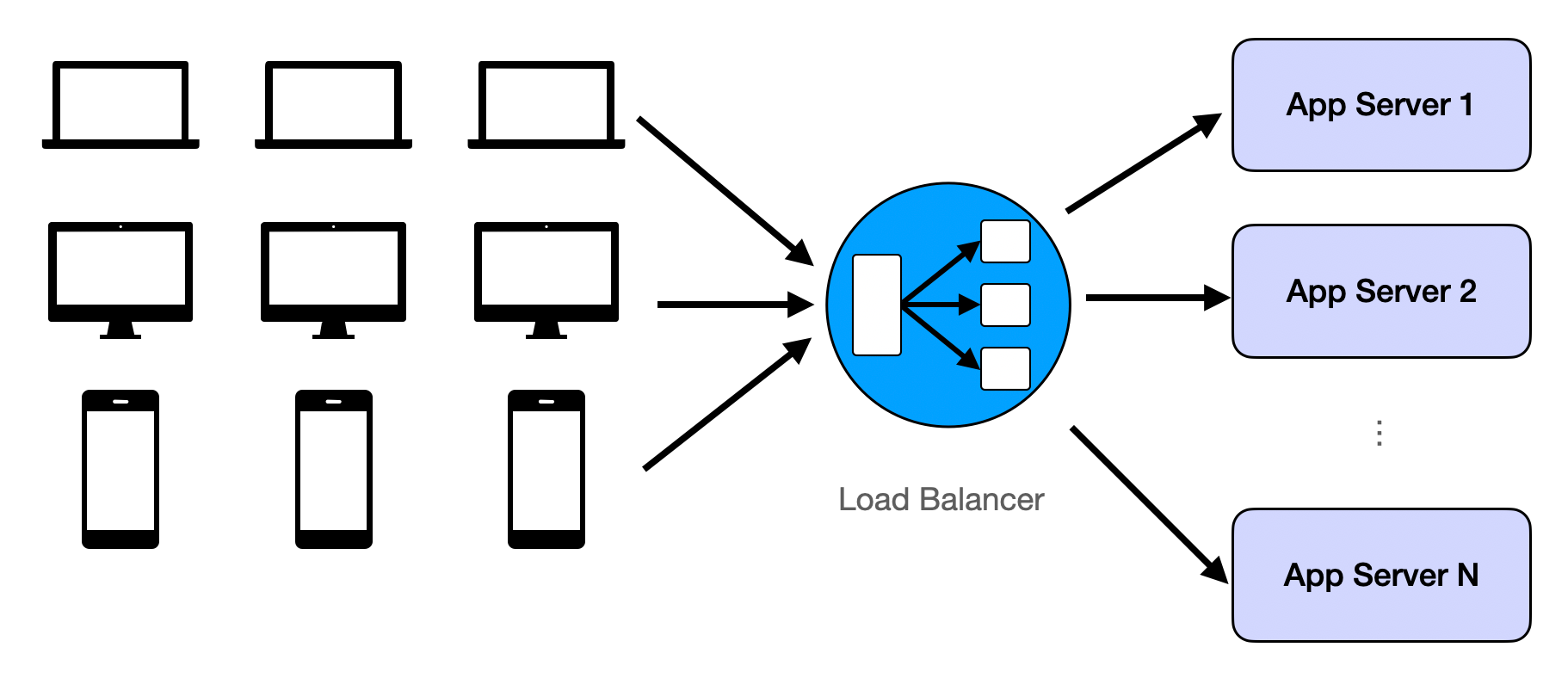

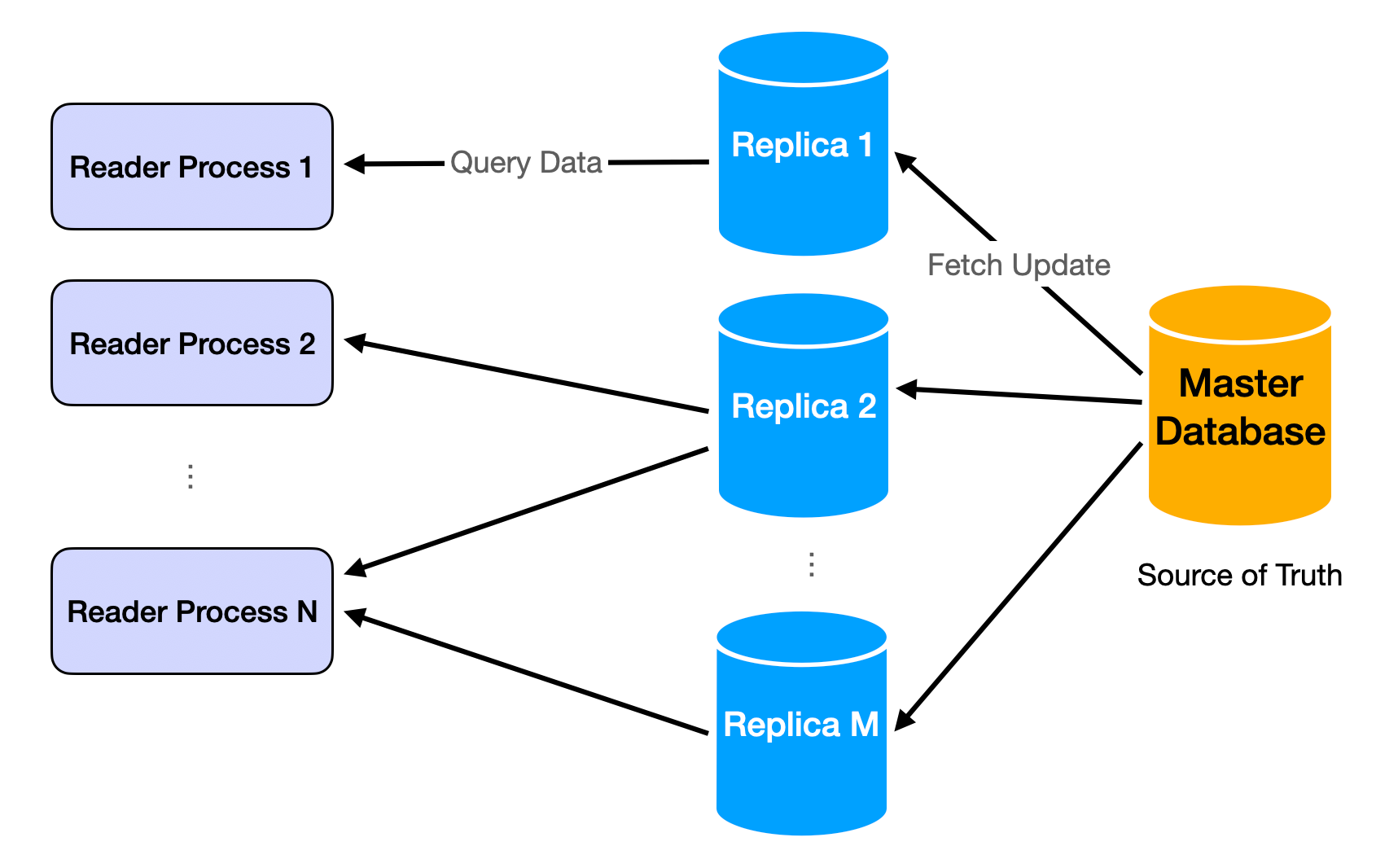

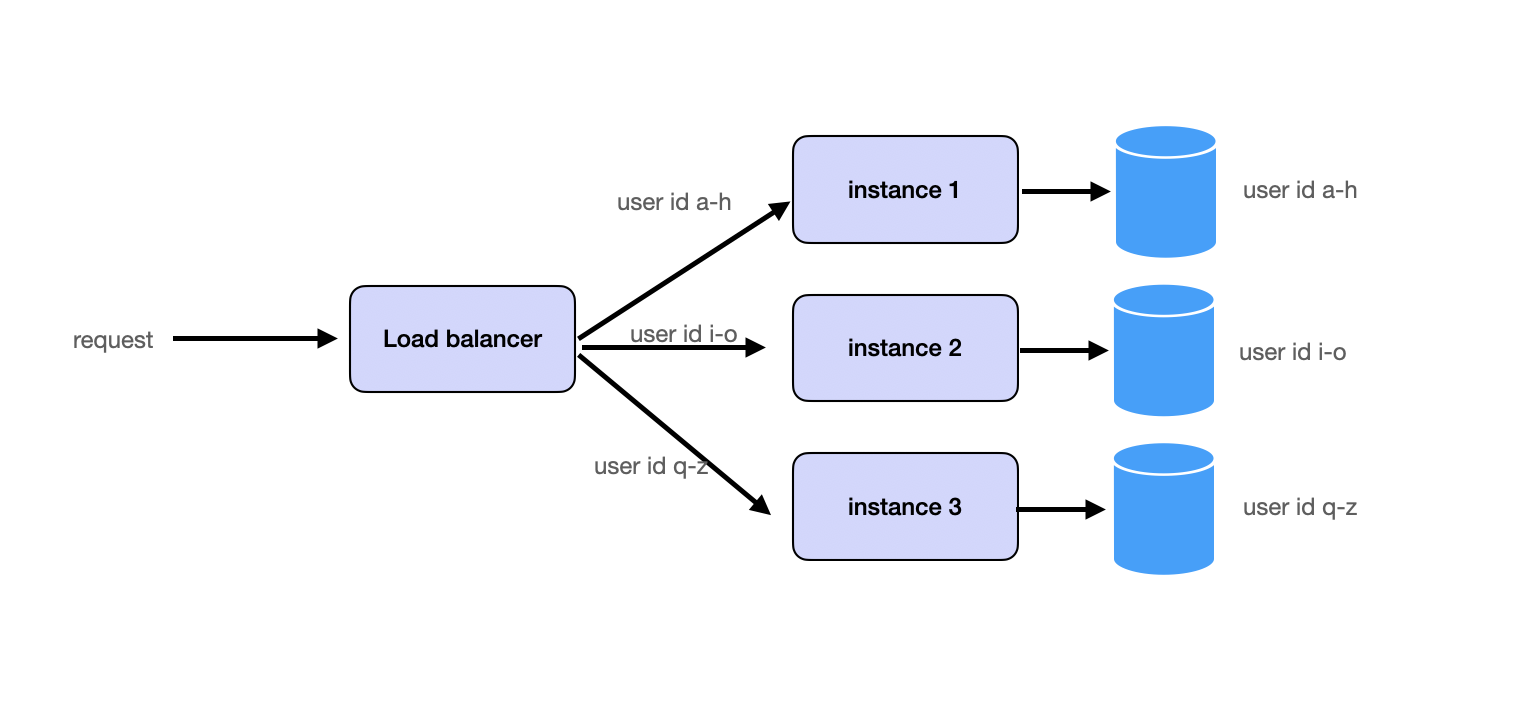

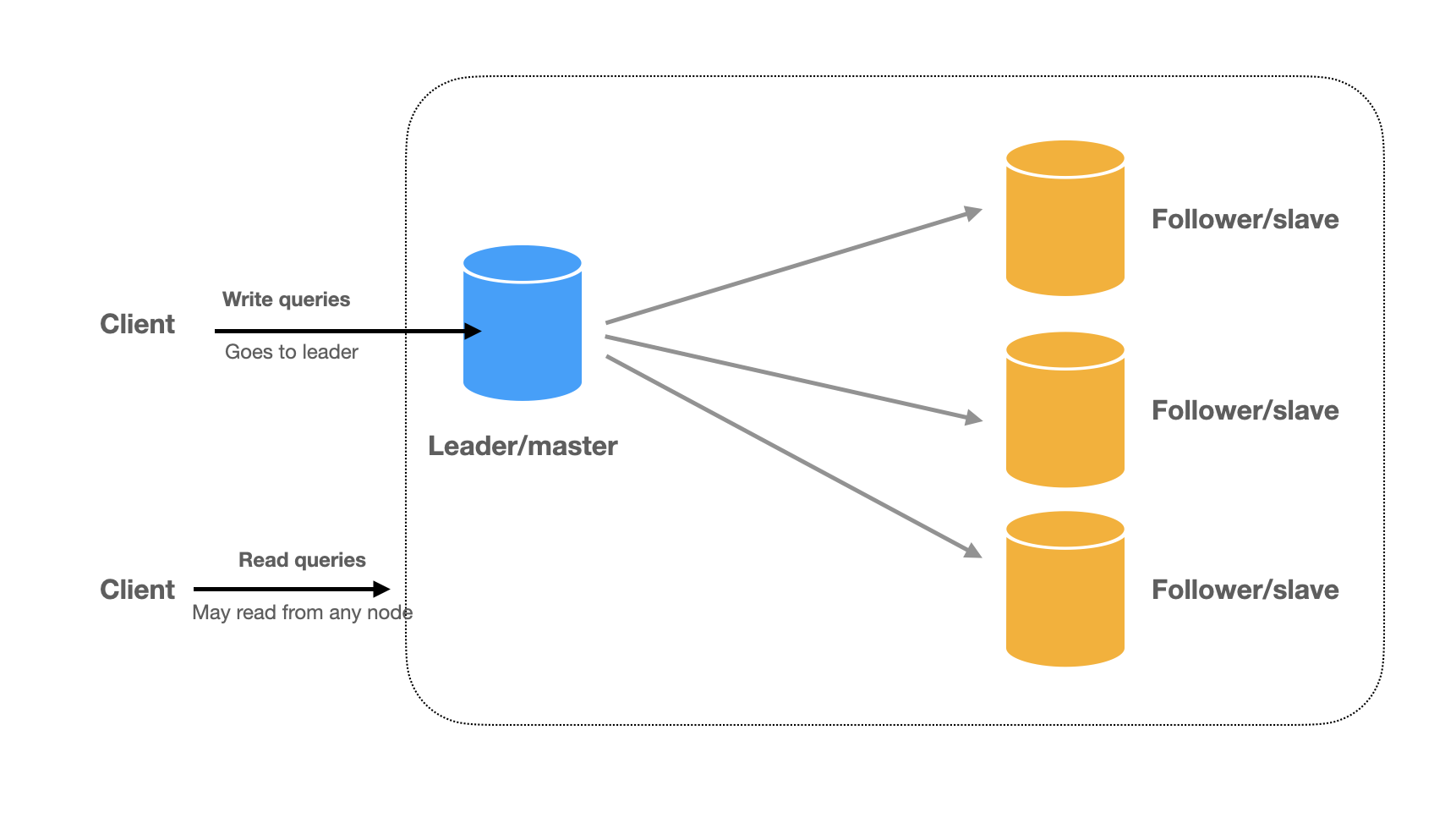

The solution is repetition. Repeat the same assets and assign users randomly to each replication. When replicated assets are server logic, it's called load balancing. When replicated assets are data, it's called database replicas.

Challenge 2: Too Much Data to Move Around

The twin challenge of too many users is too much data. Data becomes big when it's no longer possible to hold everything on one machine. Examples: Google index, all tweets on Twitter, all Netflix movies.

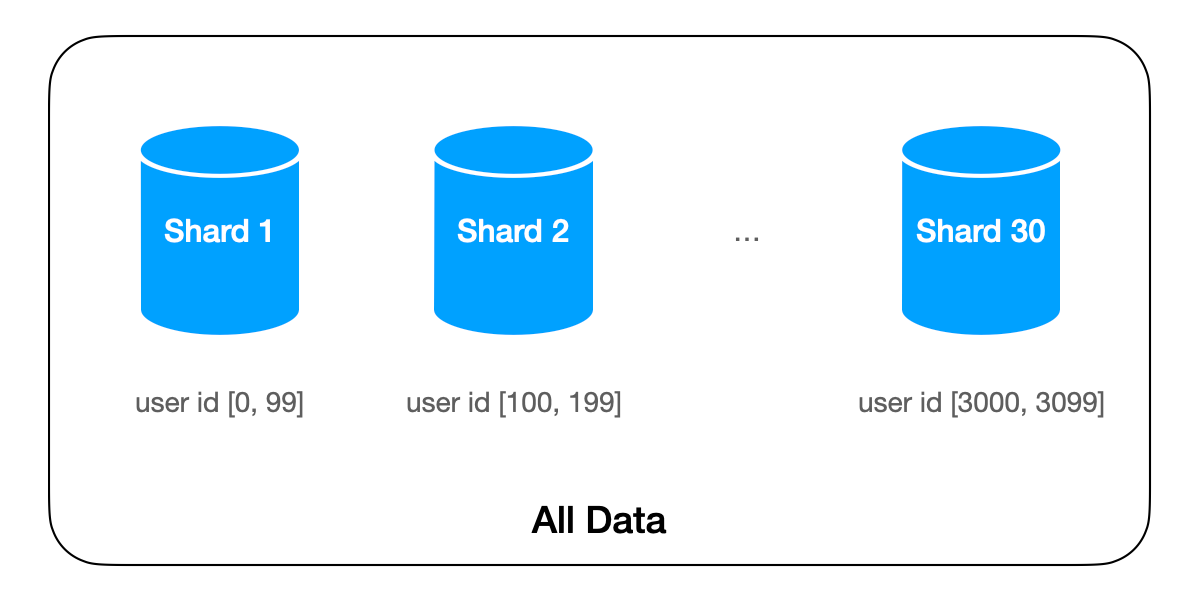

The solution is sharding: partitioning data by logic. Sharding logic groups data together. If we shard by user_id in Twitter, all tweets from one user store on the same machine.

Challenge 3: The System Should be Fast and Responsive

User-facing apps must be quick. Response time should be under 500ms. Over 1 second creates poor user experiences.

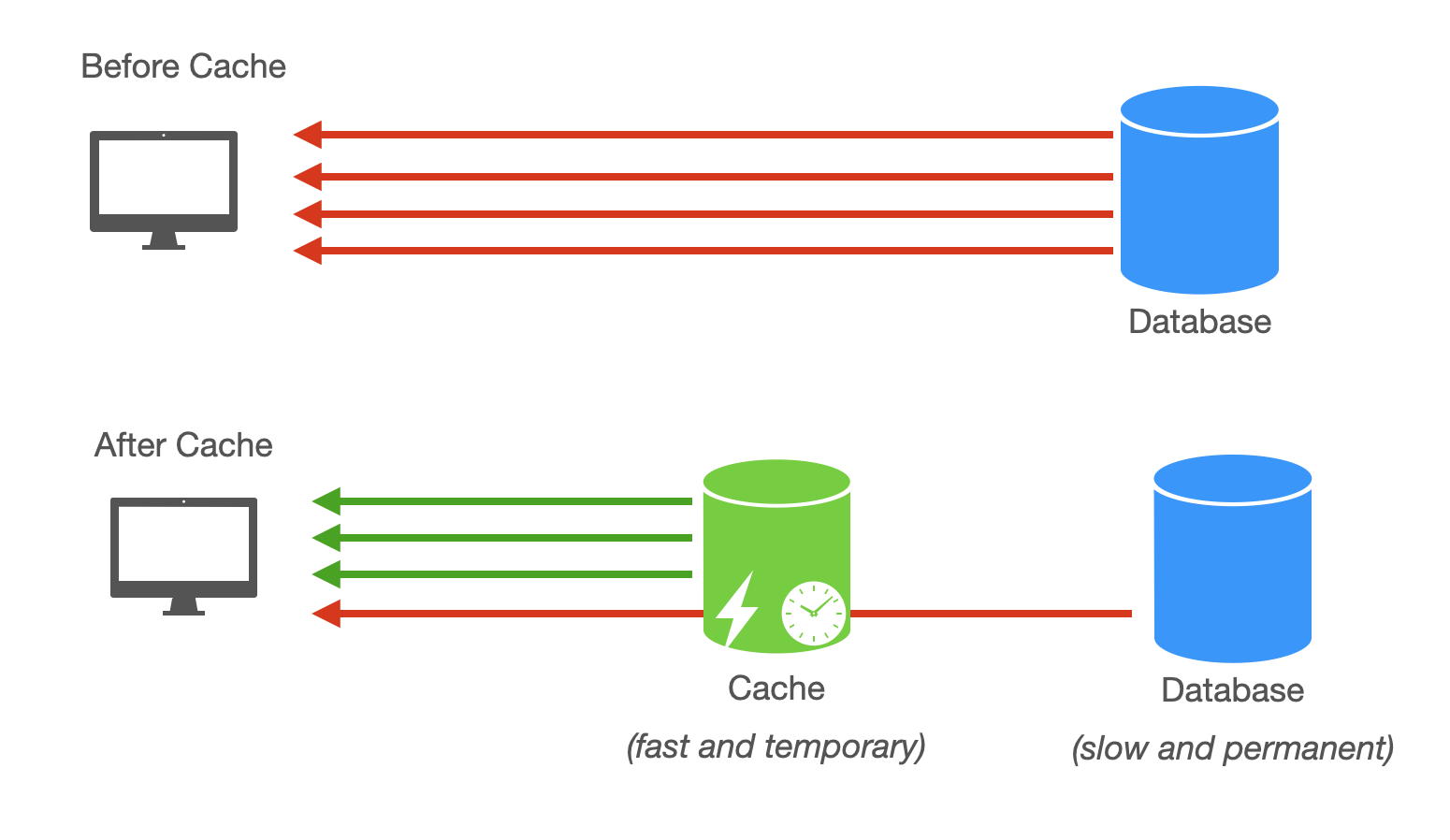

Reading is usually fast after we have replication. Read requests typically implement as queries to in-memory key-value dictionaries beside HTTP protocols. For many simple apps, latency is mostly network round time.

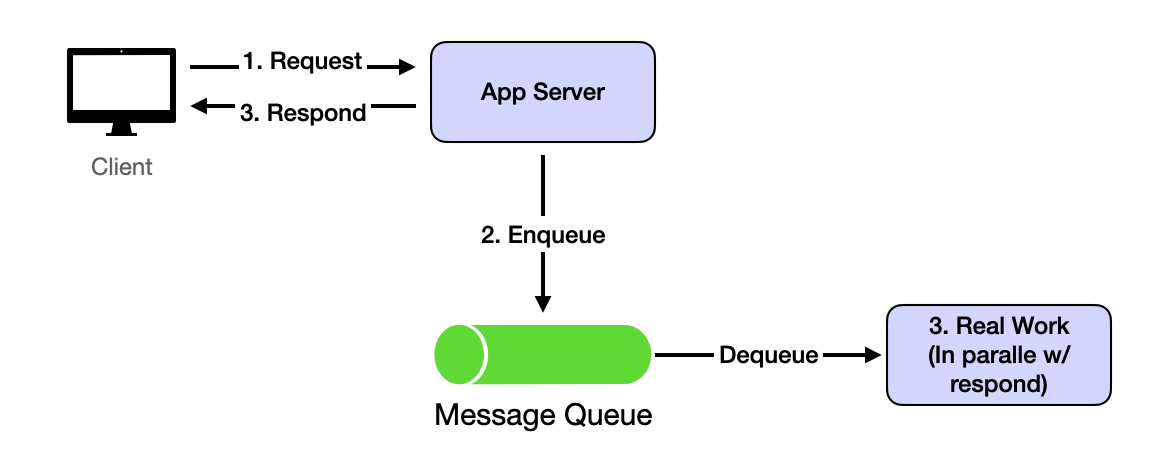

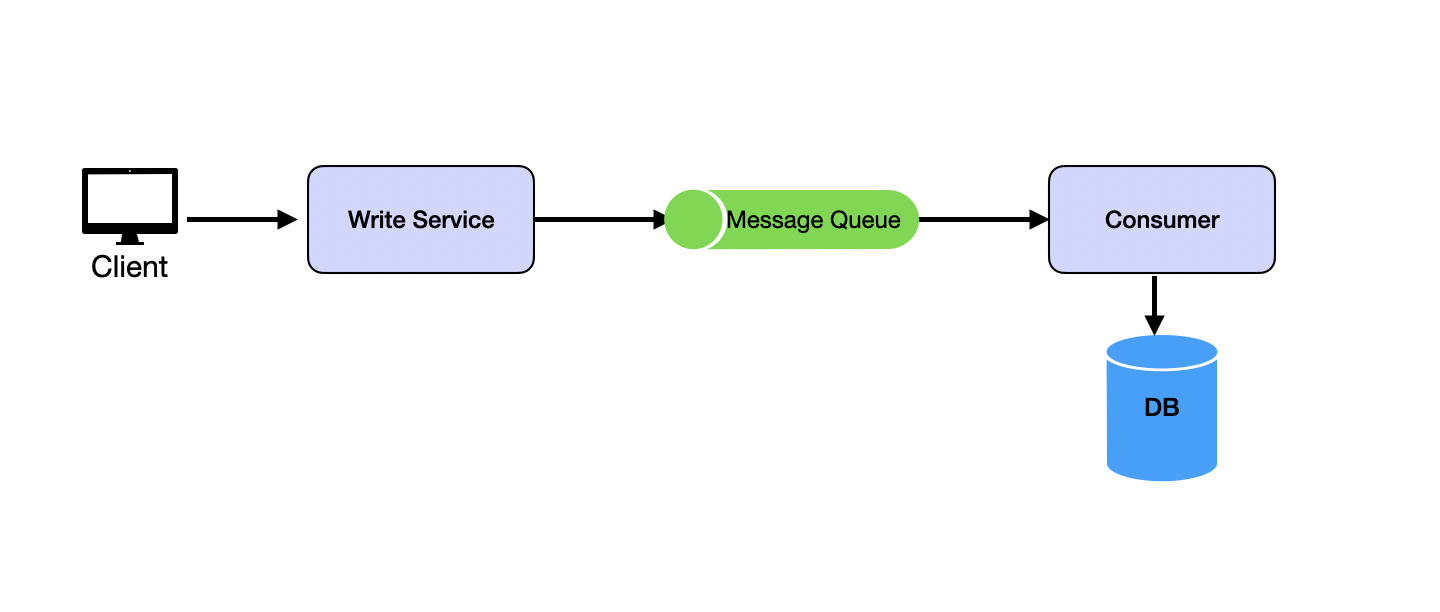

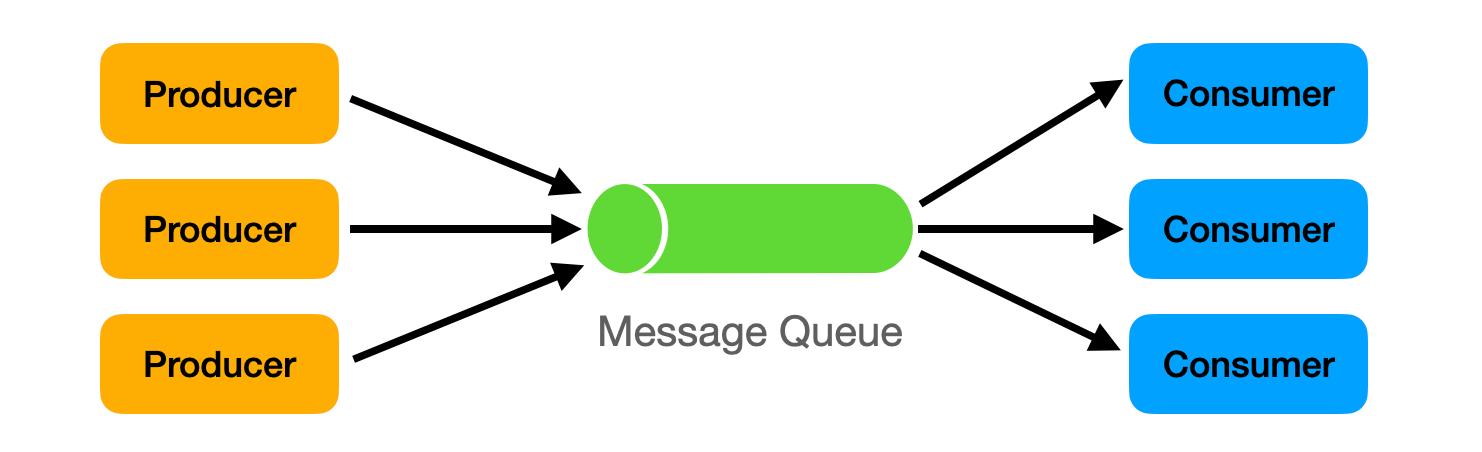

Writing is where the challenge lies. Most typical writing processes involve many data queries and updates, lasting far longer than the 1-second limit. The solution is asynchrony: write requests return immediately after servers receive data and put it in queues. Actual processing continues in backends. After receiving server responses, client-side logic has wiggle room for speedy user experiences. It can show UI before redirecting users to read results. This usually takes 1-2 seconds, enough for backend processing of actual write requests.

This implements through message queues like Kafka.

Challenge 4: Inconsistent (outdated) States

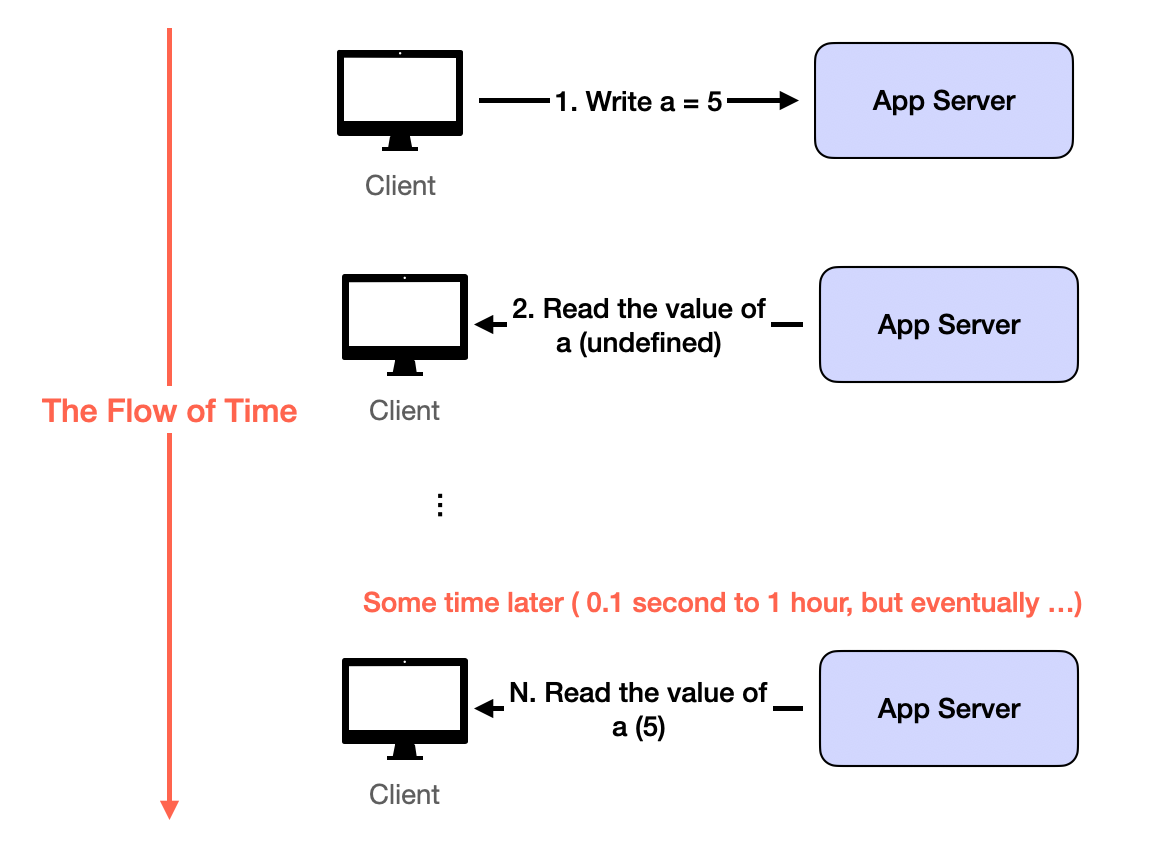

This challenge results from solving Challenge 1 and Challenge 2. With data replication and asynchronous data updates, read requests can easily see inconsistent data. Inconsistency usually means outdated: users won't see random wrong data, but old versions or deleted data.

The solution is more application-level than system-level. Outdated reads from replication and asynchronous updates eventually disappear when servers catch up. Build user experiences where seeing outdated data briefly is acceptable. This is eventual consistency.

Most apps tolerate eventual consistency well, especially compared with alternatives: losing data forever or being very slow. Exceptions are banking or payment-related apps. Any inconsistency is unacceptable, so apps must wait for all processing to finish before returning anything to users. That's why such apps feel much slower than Google Search.

Designing for Scale

Scaling systems effectively is one of the most critical aspects of satisfying non-functional requirements. Scalability is often a top priority. Below are various strategies to achieve scalable system architecture.

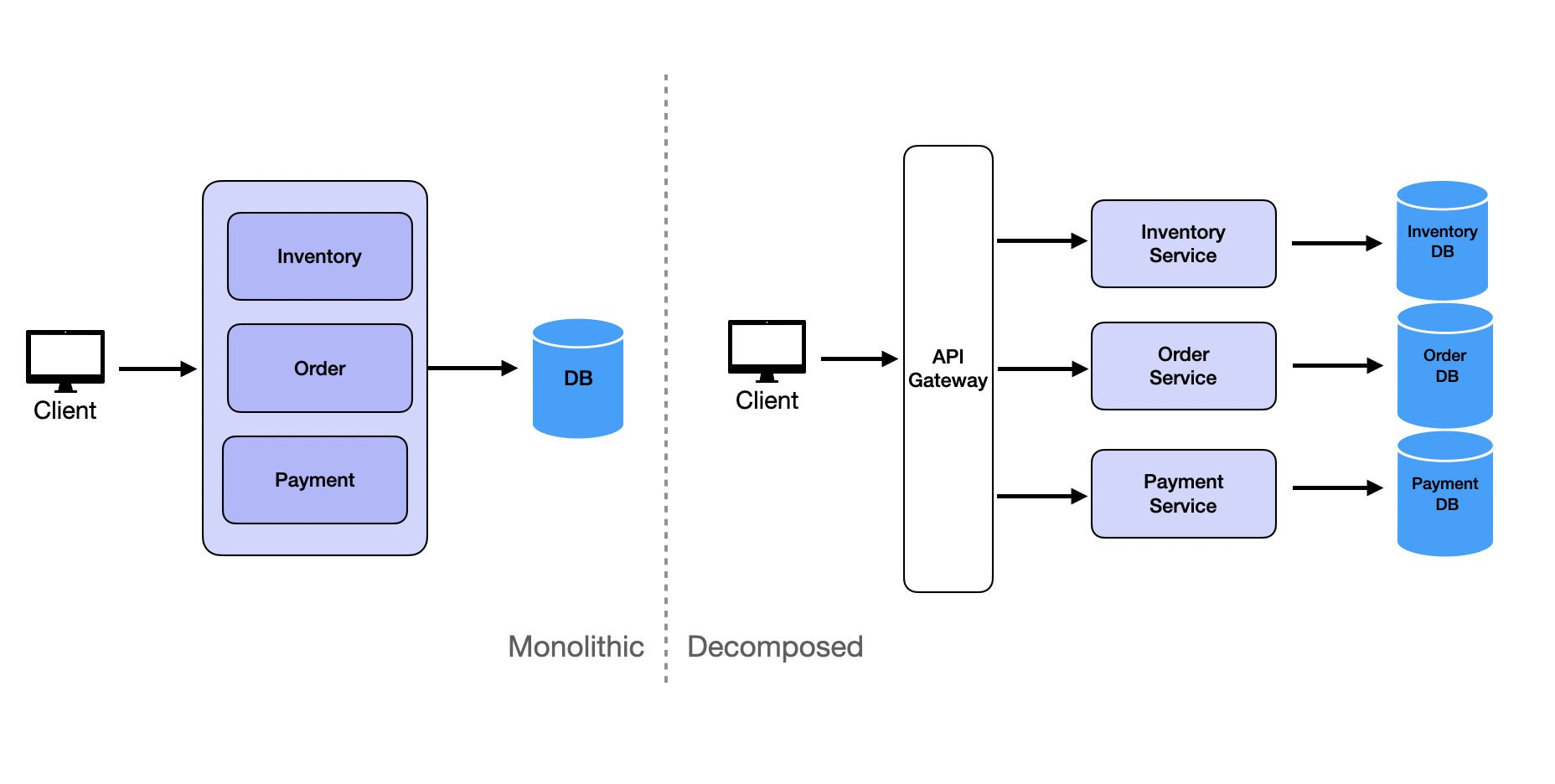

Decomposition

Decomposition breaks down requirements into microservices. The key principle is dividing systems into smaller, independent services based on specific business capabilities or requirements. Each microservice should focus on single responsibilities to enhance scalability and maintainability.

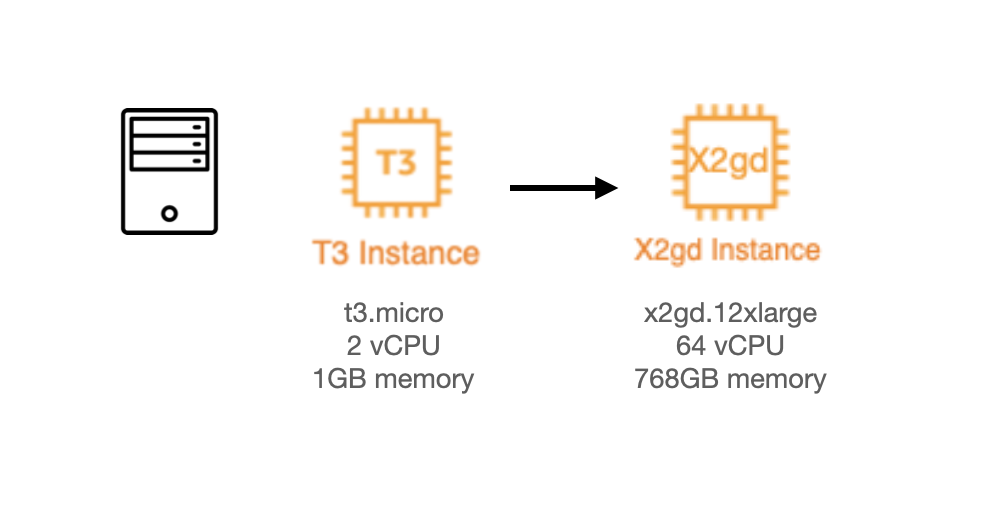

Vertical Scaling

Vertical scaling represents the brute force approach to scaling. Scale up by using more powerful machines. Thanks to cloud computing advancements, this approach has become much more feasible. In the past, organizations waited for new machines to be built and shipped. Today they spin up new instances in seconds.

Modern cloud providers offer impressive vertical scaling options. AWS provides Amazon EC2 High Memory instances with up to 24 TB of memory. Google Cloud offers Tau T2D instances specifically optimized for compute-intensive workloads.

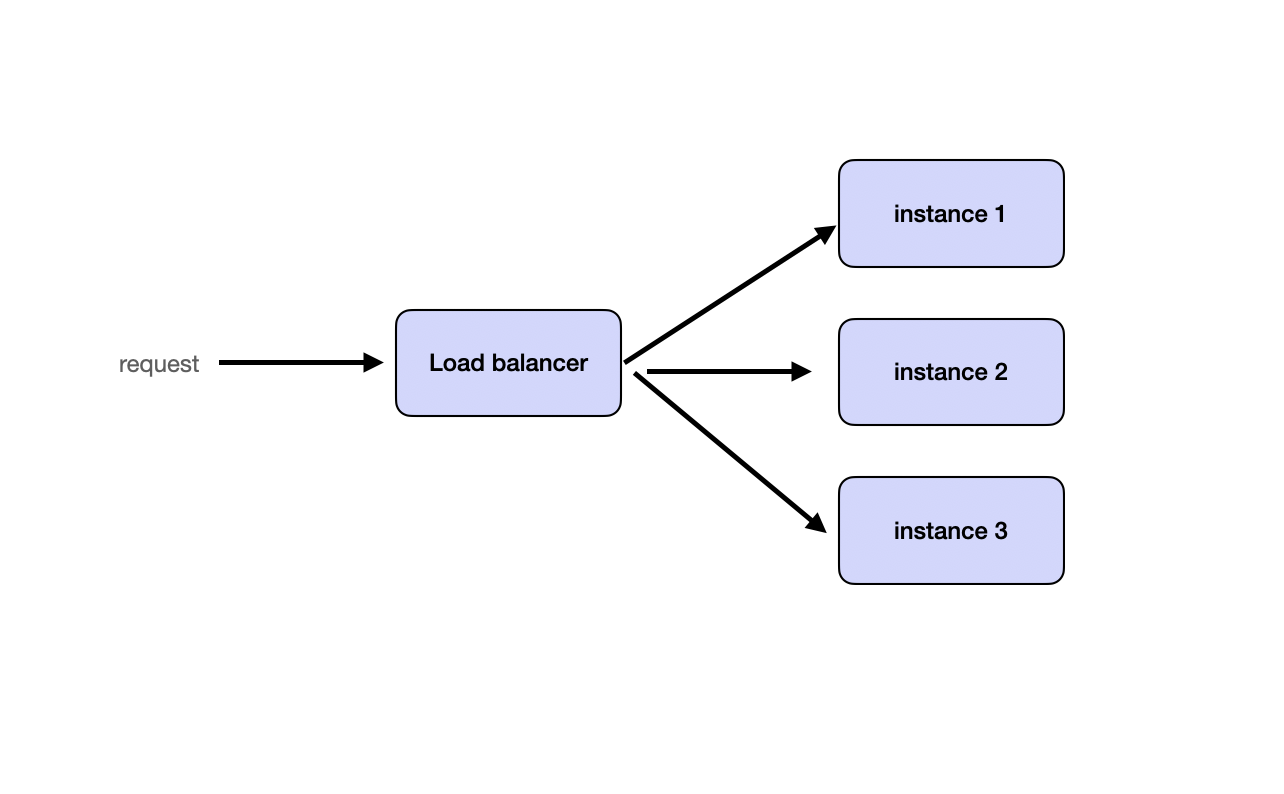

Horizontal Scaling

Horizontal scaling focuses on scaling out by running multiple identical instances of stateless services. The stateless nature of these services enables seamless distribution of requests across instances using load balancers.

Partitioning

Partitioning splits requests and data into shards and distributes them across services or databases. This can be accomplished by partitioning data based on user ID, geographical location, or another logical key. Many systems implement consistent hashing to ensure balanced partitioning.

See Database Partitioning for details.

Caching

Caching improves query read performance by storing frequently accessed data in faster memory storage, such as in-memory caches. Popular tools like Redis or Memcached effectively store hot data to reduce database load.

See Caching for details.

Buffer with Message Queues

High-concurrency scenarios often encounter write-intensive operations. Frequent database writes can overload systems due to disk I/O bottlenecks. Message queues buffer write requests, changing synchronous operations into asynchronous ones, thereby limiting database write requests to manageable levels and preventing system crashes.

See Message Queues for details.

Separating Read and Write

Whether systems are read-heavy or write-heavy depends on business requirements. Social media platforms are read-heavy because users read more than they write. IoT systems are write-heavy because users write more than they read. This is why we separate read and write operations to treat them differently.

Read and write separation typically involves two main strategies. First, replication implements leader-follower architecture where writes occur on the leader and followers provide read replicas.

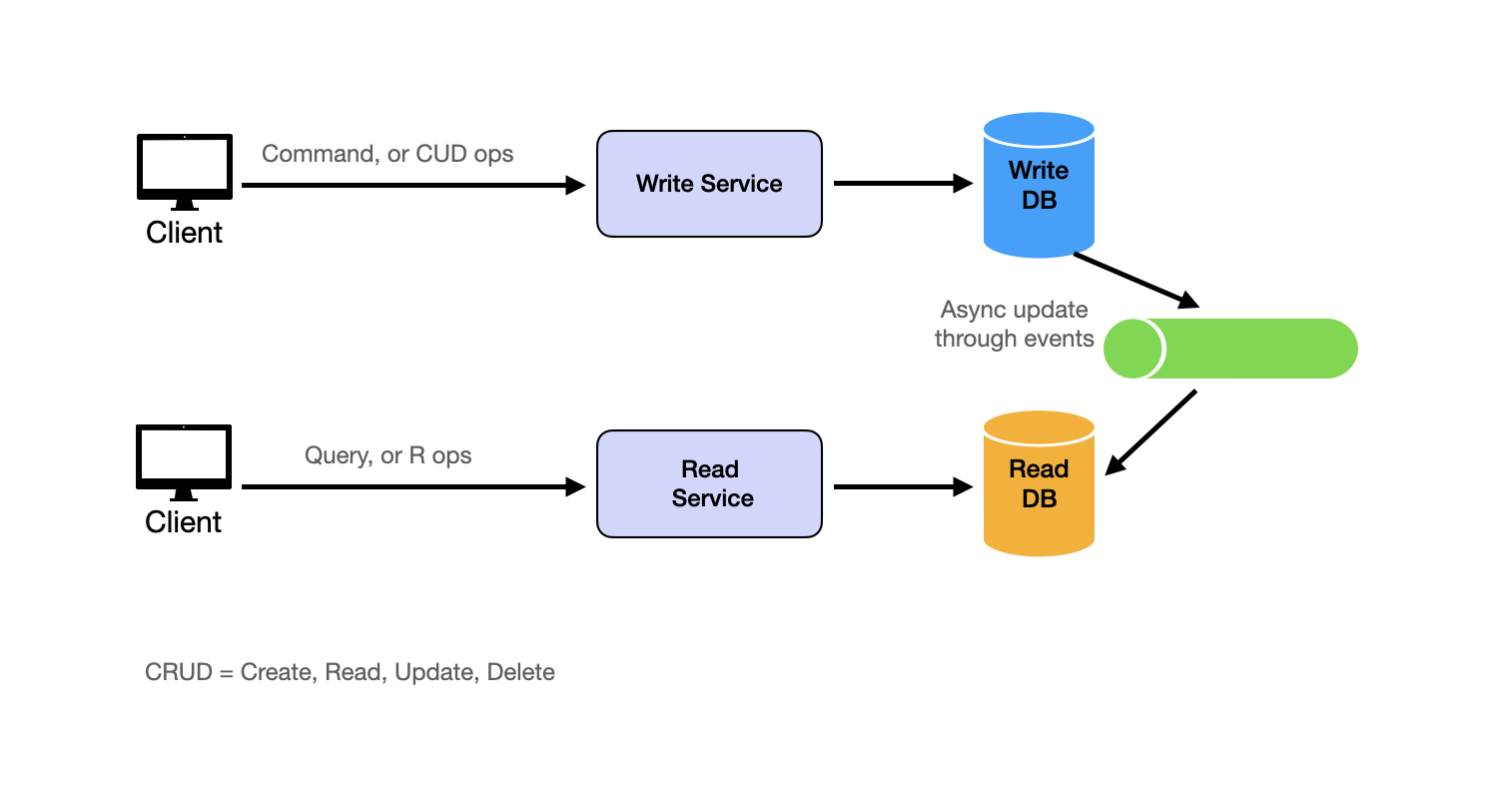

Second, the CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) pattern takes read-write separation further by using completely different models for reading and writing data. In CQRS, systems split into two parts: the command side (write side) handles all write operations (create, update, delete) using data models optimized for writes, and the query side (read side) handles all read operations using denormalized data models optimized for reads.

Changes from the command side asynchronously propagate to the query side.

For example, systems might use MySQL as source-of-truth databases while employing Elasticsearch for full-text search or analytical queries, and asynchronously sync changes from MySQL to Elasticsearch using MySQL binlog Change Data Capture (CDC).

Combining Techniques

Effective scaling usually requires multi-faceted approaches combining several techniques. Start with decomposition to break down monolithic services for independent scaling. Then, partitioning and caching work together to distribute load efficiently while enhancing performance. Read/write separation ensures fast reads and reliable writes through leader-replica setups. Finally, business logic adjustments help design strategies that mitigate operational bottlenecks without compromising user experience.

Adapting to Changing Business Requirements

Adapting business requirements offers practical ways to handle large traffic loads. While not strictly technical approaches, understanding these strategies demonstrates valuable experience and critical thinking skills in interview settings.

Consider weekly sales event scenarios. Instead of running all sales simultaneously for all users, distribute load by allocating specific days for different product categories for specific regions. Baby products might feature on Day 1, followed by electronics on Day 2. This approach ensures more predictable traffic patterns and enables better resource allocation such as pre-loading cache for upcoming days and scaling out read replicas for specific regions.

Another example involves handling consistency challenges during high-stakes events like eBay auctions. By temporarily displaying bid success messages on frontends, systems can provide seamless user experiences while backends resolve consistency issues asynchronously. Users eventually see correct bid status after auctions end.

While not technical solutions, bringing these up in interviews demonstrates your ability to think through problems and provide practical solutions.

Master Template

Here is the common template to design scalable services and solve many system design problems:

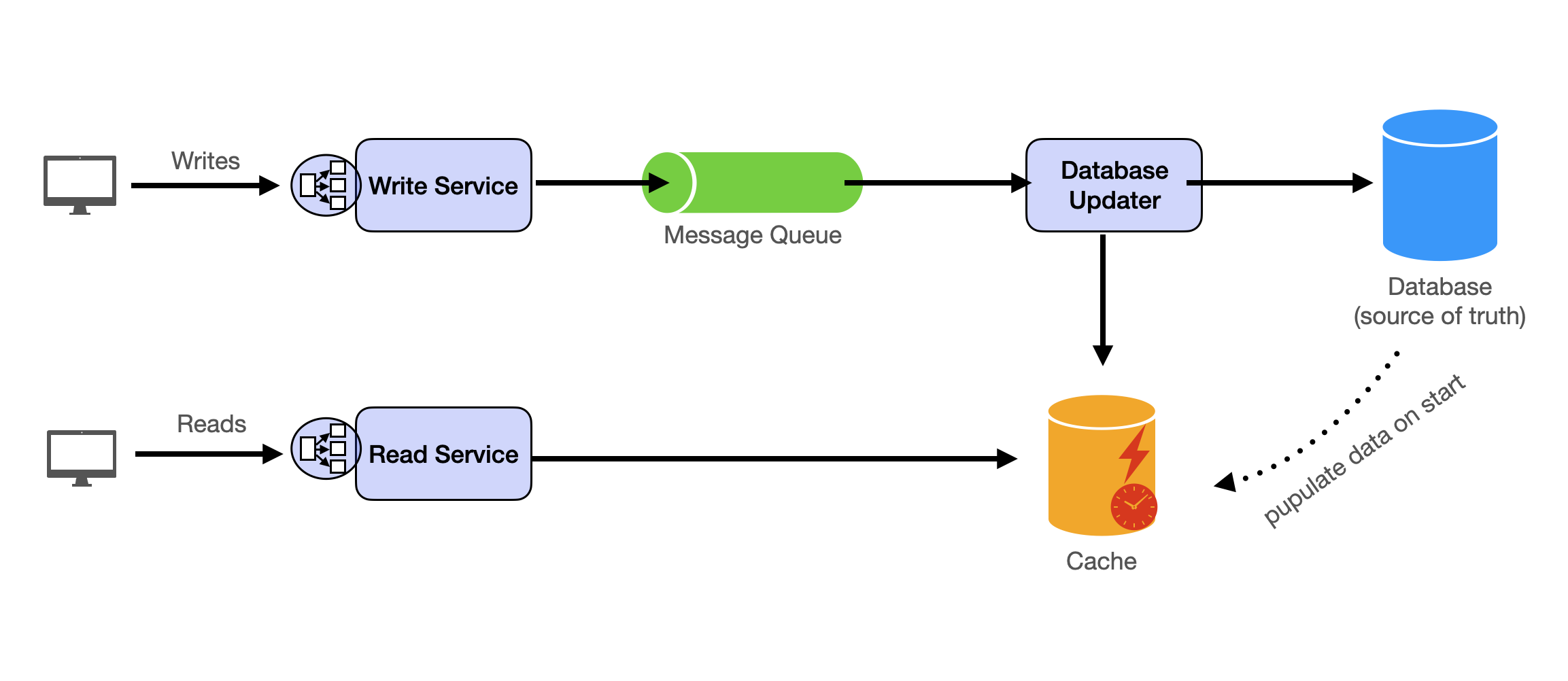

High-level takeaway: write to message queue and have consumers/workers update database and cache. Read from cache.

Component Breakdown

Stateless Services are scalable and can be expanded by adding new machines and integrating them through load balancers. Write Service receives client requests and forwards them to message queues. Read Service handles read requests from clients by accessing caches.

Databases serve as cold storage and source of truth. We do not normally read directly from databases since it can be slow when request volume is high.

Message Queues buffer between writer services and data storage. Producers (comprised of write services) send data changes to queues. Consumers update both databases and caches. Database Updater (asynchronous workers) updates databases by retrieving jobs from message queues. Cache Updater (asynchronous workers) refreshes caches by fetching jobs from message queues.

Caches facilitate fast and efficient read operations.

Dataflow Path

Almost all applications break down into read requests and write requests. Because read and write have completely different implications (read doesn't mutate; write mutates database), we discuss write path and read path separately.

Read path: For modern large-scale applications with millions of daily users, we almost always read from cache instead of from databases directly. Databases act as permanent storage solutions. Asynchronous jobs frequently transfer data from databases to caches.

Write path: Write requests push into message queues, allowing backend workers to manage writing processes. This approach balances processing speeds of different system components, offering responsive user experiences.

Message queues are essential to scaling out systems to handle write requests. Producers insert messages into queues. Consumers retrieve and process messages asynchronously.

The necessity of message queues arises from varying processing rates (producers and consumers handle data at different speeds, necessitating buffers) and fault tolerance (they ensure persistence of messages, preventing data loss during failures).

Main Components

Common system design problems have been solved. Engineers developed reusable tools called components. These fit into most systems.

System design interviews test your ability to assemble components correctly. Learn how each technology works and when to use it. That's the game.

Each component section follows this structure: first, the problem it solves and when to use it. Second, how it works technically. Third, common implementations with trade-offs.

Microservices

The Problem

A startup builds an e-commerce application. Everything lives in one codebase: product catalog, checkout, payments, user accounts. The application processes 100 orders per day. This monolithic approach works.

Two years later, traffic grows to 10,000 orders per day. The checkout service needs more servers. But you can't scale just checkout. You must scale the entire monolith. The payment team wants to deploy fraud detection. They can't. Deploying requires coordinating with every other team. A bug in the catalog crashes the entire application, taking down checkout and payments.

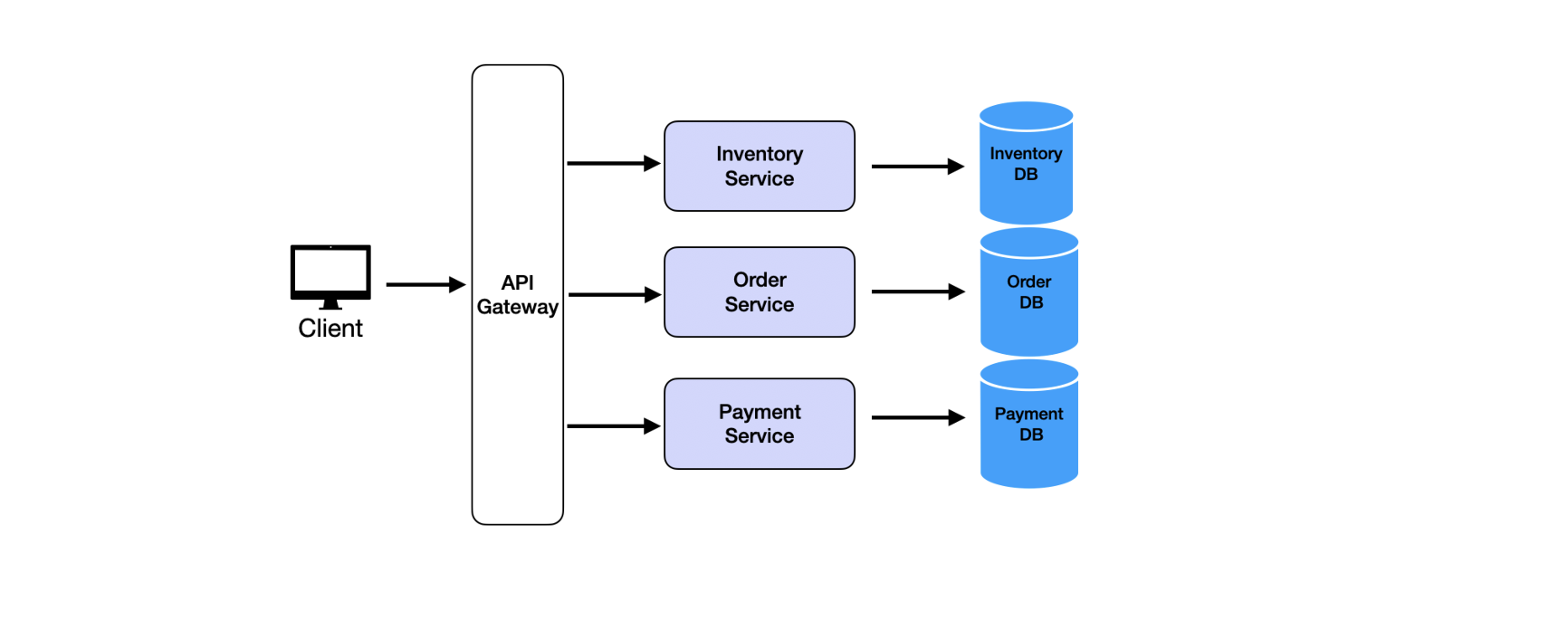

Microservices solve this by splitting applications into independent services, each handling one business function. An e-commerce system splits into separate services: Product Service, Cart Service, User Service, Order Service, Payment Service. Each service deploys independently, scales independently, and fails independently.

How Microservices Work

Each service runs as a separate process. Services communicate through APIs, typically REST over HTTP or gRPC. The Payment Service calls the Order Service to verify order details. The Order Service calls the Inventory Service to check stock. No service talks directly to another service's database.

Each service owns its database. The User Service manages the User Database. The Order Service manages the Order Database. This prevents tight coupling. If the User Service changes its database schema, other services don't break.

Services register with a service registry (like Consul or Eureka). When the Payment Service starts, it announces its location. When another service needs to call Payment Service, it asks the registry where to find it. This is service discovery.

Services scale independently. Black Friday hits and checkout traffic spikes. Spin up 10 more Order Service instances. The Product Service continues running with just 2 instances. Different services have different load patterns.

Fault isolation prevents cascading failures. If the Recommendation Service crashes, checkout still works. Services use circuit breakers to detect failures and stop sending requests to broken services.

For deeper understanding of microservices architecture, communication patterns, and service mesh, see Microservices and Monolithic Architecture.

Common Implementations

Spring Boot is the standard for Java microservices. It includes built-in support for REST APIs, service discovery, and distributed tracing. Use it for enterprise systems requiring mature tooling and strong typing.

Node.js with Express works well for lightweight microservices. It offers fast development and a large npm ecosystem. Use it for TypeScript microservices or teams preferring JavaScript.

Go with frameworks like Gin or Echo delivers high performance with built-in concurrency. Use it for high-throughput services requiring low latency, like real-time bidding or stream processing.

Relational Databases

The Problem

A bank processes money transfers. User A sends $100 to User B. The system must subtract $100 from A's account and add $100 to B's account. Both operations must succeed or both must fail. Partial completion is unacceptable. User A loses $100 but User B never receives it.

This requires consistency. Data must remain accurate across related records. Relational databases solve this through structured storage and ACID transactions.

Relational databases organize data into tables. Each table has rows and columns. A Users table has columns for user_id, name, and email. Each row represents one user. Tables link through relationships. An Orders table references Users through a user_id column.

Use relational databases when consistency is critical. Financial transactions, inventory management, and user account systems require accurate, structured data. NoSQL offers flexibility. Relational databases offer guarantees.

How Relational Databases Work

Tables store structured data. Each table represents an entity: Users, Orders, Products. Columns define the schema: data types and constraints. Rows contain actual records.

Primary keys uniquely identify each row. The Users table has user_id as its primary key. No two users share the same user_id. Foreign keys create relationships between tables. The Orders table has a user_id column referencing the Users table. This links each order to a specific user.

Three relationship types exist:

- One-to-one: each user has exactly one profile

- One-to-many: one user has many orders

- Many-to-many: many students enroll in many classes, requiring a junction table storing both student_id and class_id

ACID properties guarantee data correctness:

- Atomic: transactions complete fully or not at all

- Consistent: transactions move the database from one valid state to another

- Isolated: concurrent transactions don't interfere

- Durable: committed transactions persist even after crashes

SQL enables powerful queries. Join tables to combine data. Filter with WHERE clauses. Aggregate with GROUP BY. This expressiveness makes relational databases ideal for complex business logic.

For comprehensive coverage of relational databases, indexing strategies, and query optimization, see Relational Database Fundamentals and Database Partitioning.

Common Implementations

PostgreSQL is the most feature-rich open-source relational database. It supports advanced data types (JSON, arrays), full-text search, and custom functions. Use it for applications requiring complex queries or analytical workloads alongside transactional operations.

MySQL is the most widely deployed open-source relational database. It offers excellent read performance and straightforward replication. Use it for web applications prioritizing simplicity and broad hosting support.

Amazon RDS is a managed relational database service supporting PostgreSQL, MySQL, and others. It handles backups, patches, and scaling automatically. Use it for cloud-based applications avoiding operational overhead.

NoSQL Databases

The Problem

Instagram stores user posts. Each post has an image, caption, hashtags, location, timestamp, and comments. Comments contain text, author, and nested replies. Fitting this into relational tables requires many joins. The Posts table joins to Comments, which joins to Users, which joins to Locations. Reading one post requires querying five tables.

The schema changes weekly. Product adds "story reactions" one week and "polls" the next. Each schema change requires database migrations coordinating across teams. Development slows.

NoSQL databases solve this by storing flexible, nested data without rigid schemas. One document stores everything: post image, caption, comments array, location object. No joins required. Schema changes don't require migrations.

Use NoSQL when data structure varies by record. Use it when you add new fields frequently. Use it when scaling to millions of writes per second across distributed servers. Trade relational guarantees for flexibility and horizontal scalability.

How NoSQL Databases Work

NoSQL databases come in four types, each optimized for different access patterns.

- Key-value stores work like hash maps. Store session data with key

session_abc123mapping to JSON{"user_id": 456, "login_time": "..."}. Redis and Memcached are examples. Use them for caching and session management. - Document databases store JSON-like documents. Each document is self-contained with nested fields. MongoDB is a document database. Use it for content management where records have varying schemas.

- Column-family stores organize data by column instead of row. Cassandra stores time-series data efficiently. Use them for high-write workloads like logs and analytics.

- Graph databases store nodes and edges. Neo4j models relationships as first-class citizens. Use them for social networks and recommendation engines.

NoSQL databases sacrifice ACID guarantees for availability and partition tolerance. Most offer eventual consistency: writes propagate to all nodes within seconds. Strong consistency is optional but reduces availability.

For in-depth exploration of NoSQL databases and distributed database concepts, see NoSQL Database Fundamentals and CAP and PACELC Theorem.

Common Implementations

MongoDB is the most popular document database. It supports rich queries including filters, aggregations, and text search. Use it for applications where documents have varying schemas, like product catalogs or user-generated content.

Redis is an in-memory key-value store delivering sub-millisecond latency. It supports data structures beyond simple values: lists, sets, sorted sets. Use it for caching, real-time leaderboards, and rate limiting.

Apache Cassandra is a distributed column-family database with no single point of failure. It handles millions of writes per second by distributing data across nodes. Use it for time-series data, event logging, and high-write applications.

Amazon DynamoDB is a fully managed key-value and document database. It auto-scales and offers single-digit millisecond latency at any scale. Use it for serverless applications or unpredictable traffic patterns.

Object Storage

The Problem

Netflix stores 100 million video files. Users upload profile pictures. YouTube hosts billions of thumbnails. These files vary in size from kilobytes to gigabytes. Storing them in relational databases is inefficient. Databases optimize for structured queries, not large binary files.

File systems work but don't scale. A single server holds limited storage. Adding more servers requires manual partitioning logic. Replication for durability becomes complex. Accessing files requires knowing which server holds them.

Object storage solves this by treating each file as an object with a unique ID. Store a video with key videos/user123/vacation.mp4. Retrieve it later using that key. The system handles distribution, replication, and scaling automatically.

Use object storage for static assets like images and videos. Use it for backups requiring long-term retention. Use it for data lakes storing raw data for analytics. Don't use it for frequently updated files or low-latency operations.

How Object Storage Works

Objects live in buckets. A bucket is a container holding millions of objects. Each object has three parts: a unique key (like photos/cat.jpg), binary data (the actual file), and metadata (size, content type, custom tags).

There are no folders. Keys look like file paths but the storage is flat. The key images/2024/cat.jpg is just a string. No /images/ directory exists.

Clients interact through RESTful APIs. Upload with PUT requests. Download with GET requests. Delete with DELETE requests. The API abstracts the underlying distributed storage.

Object storage replicates data across multiple nodes and regions. Upload a file and the system automatically copies it to 3+ servers. If one server fails, replicas ensure data survives. This achieves high durability.

Versioning keeps multiple versions of the same object. Overwrite report.pdf and the old version remains accessible. This protects against accidental deletions. Lifecycle policies automatically move old objects to cheaper storage tiers after 90 days or delete them after one year.

Consistency models vary. S3 offers strong read-after-write consistency. Upload an object and immediately read it. Eventual consistency is cheaper but reads might return stale data briefly.

For detailed coverage of object storage systems and blob storage patterns, see Object Storage and Blob Storage.

Common Implementations

Amazon S3 is the industry standard. It offers virtually unlimited storage, automatic replication, and integration with AWS services. Use it for most object storage needs, especially in AWS environments.

Google Cloud Storage provides multi-regional storage with strong consistency. It integrates tightly with BigQuery for analytics. Use it for Google Cloud applications or when running analytics on stored data.

Azure Blob Storage is Microsoft's object storage. It offers hot, cool, and archive tiers for cost optimization. Use it for Azure-based applications or hybrid cloud scenarios.

Cache

The Problem

An e-commerce site displays product pages. Each page load queries the database for product details, price, and inventory. The database handles 1,000 requests per second. Most requests fetch the same 100 popular products repeatedly.

Database queries take 50ms each. Users experience slow page loads. The database CPU hits 90%. Adding more database servers is expensive. Most queries return identical data from minutes ago.

Caching solves this. Store frequently accessed data in fast memory. Serve repeated requests from cache instead of hitting the database. Response time drops from 50ms to 1ms. Database load drops by 80%.

Use caching when reads vastly outnumber writes. Use it when staleness is acceptable (product prices can be 5 minutes old). Use it to reduce database load and improve response times.

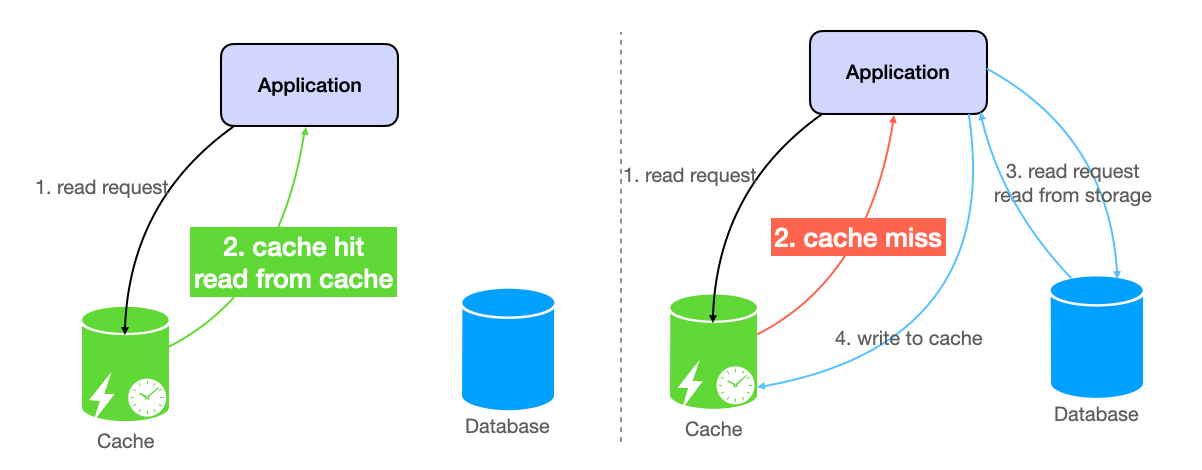

How Caches Work

The application checks cache before querying the database. Cache hit: data exists in cache, return immediately. Cache miss: data absent, query database, store result in cache, return to user.

This is cache-aside pattern. The application manages cache explicitly. Alternatives include write-through (writes update cache and database simultaneously) and write-behind (writes update cache first, then asynchronously sync to database).

Caches have limited memory. Eviction policies determine what to remove when full:

- LRU (Least Recently Used): removes items not accessed recently

- LFU (Least Frequently Used): removes items accessed rarely

- TTL (Time To Live): removes items after expiration

Cache invalidation keeps data fresh. Set TTL to 5 minutes for product prices. After 5 minutes, cache expires and fetches fresh data. For critical updates, invalidate cache explicitly when data changes. Product price updates? Delete that product's cache entry immediately.

Trade-offs exist. Longer TTL means stale data but less database load. Shorter TTL means fresher data but more database hits.

For comprehensive coverage of caching strategies, eviction policies, and cache patterns, see Caching Fundamentals.

Common Implementations

Redis is an in-memory cache delivering sub-millisecond latency. It supports data structures like strings, lists, sets, and sorted sets. Use it for session storage, leaderboards, and general-purpose caching.

Memcached is a simpler in-memory cache optimized for basic key-value storage. It's faster for simple operations but lacks Redis's data structures. Use it for straightforward caching needs prioritizing simplicity.

CDNs like Cloudflare act as distributed caches for static assets. They cache images, CSS, and JavaScript files at edge locations worldwide. Use them for content delivery optimization.

CDN (Content Delivery Network)

The Problem

A news website hosts videos in a New York data center. A user in Tokyo clicks play. The video request travels 11,000 kilometers to New York and back. Network latency alone is 200ms. The video stutters.

Millions of users watch the same viral video. The origin server in New York handles 10,000 requests per second. Bandwidth costs spike. The server struggles. Some requests time out.

CDNs solve this by caching static content on edge servers distributed globally. Tokyo users fetch videos from a Tokyo edge server. Latency drops to 5ms. The origin server handles far fewer requests because edge servers absorb most traffic.

Use CDNs for static assets: images, videos, CSS, JavaScript files. Use them for high-traffic global applications. Use them to reduce origin server load and improve user experience worldwide.

How CDNs Work

Upload your static files to the CDN provider. The CDN replicates them to hundreds of edge servers across continents. Edge servers sit in major cities: Los Angeles, London, Tokyo, Sydney.

A user in London requests https://cdn.example.com/logo.png. DNS routes the request to the nearest edge server in London. Cache hit: the edge server has the file and serves it instantly (5ms). Cache miss: the edge server doesn't have it, fetches from origin (200ms), caches locally, then serves it. Subsequent London users get cache hits.

Files cache according to TTL (Time To Live). Set TTL to 24 hours for a logo that rarely changes. Set TTL to 5 minutes for frequently updated content. After TTL expires, the edge server fetches fresh content from origin.

CDNs reduce latency through geographic proximity. They reduce origin load by serving cached copies. They improve availability by distributing traffic across many servers.

For detailed exploration of CDN architecture and content delivery optimization, see Content Delivery Networks.

Common Implementations

Cloudflare offers a global CDN with built-in DDoS protection and web application firewall. It's easy to set up and includes free tiers. Use it for small to mid-sized applications prioritizing security and ease of use.

AWS CloudFront integrates tightly with AWS services like S3 and Lambda@Edge. It supports custom cache behaviors and edge computing. Use it for AWS-based applications requiring programmatic cache control.

Akamai operates the largest CDN network with the most edge servers. It offers advanced features like image optimization and predictive prefetching. Use it for large enterprises with complex global delivery needs.

Message Queues

The Problem

Black Friday. An e-commerce site receives 10,000 orders per minute. The Order Service creates orders and calls the Payment Service. Payment processing takes 2 seconds per order. The Order Service waits for each payment to complete before accepting the next order. Orders pile up. Users see timeout errors.

The Payment Service crashes for 30 seconds. During that window, 5,000 orders arrive. All fail. No retry mechanism exists. Revenue is lost.

Message queues solve both problems. The Order Service sends order messages to a queue and responds immediately to users. The Payment Service processes messages from the queue at its own pace. If Payment crashes, messages wait in the queue. When it recovers, processing resumes. No orders are lost.

Use message queues to decouple services. Use them to buffer traffic spikes. Use them to ensure reliable message delivery despite failures.

How Message Queues Work

Producers publish messages to the queue. The Order Service publishes an order message: {"order_id": 123, "user_id": 456, "total": 99.99}.

The queue stores messages durably. If the queue server crashes, messages persist on disk and survive. Messages wait until consumers are ready.

Consumers pull messages from the queue and process them. The Payment Service pulls the order message and charges the user. After successful processing, the consumer sends an acknowledgment to the queue. The queue deletes the acknowledged message.

If processing fails, the consumer doesn't acknowledge. The queue re-delivers the message to another consumer. This ensures at-least-once delivery. Messages are never lost.

Dead letter queues handle poison messages. If a message fails processing 5 times, it moves to a dead letter queue for manual inspection. This prevents broken messages from blocking the queue forever.

FIFO (First In First Out) queues guarantee message order. Order messages for the same user process in sequence. Standard queues allow out-of-order processing for higher throughput.

For comprehensive understanding of message queues, event streaming, and asynchronous communication patterns, see Message Queue Fundamentals.

Common Implementations

RabbitMQ is a traditional message broker supporting complex routing. It offers flexible exchange types for routing messages to multiple queues. Use it for systems requiring sophisticated message routing and acknowledgments.

Apache Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform designed for high throughput. It handles millions of messages per second and retains them for replay. Use it for event sourcing, real-time analytics, and log aggregation.

AWS SQS is a fully managed queue service requiring zero operational overhead. It auto-scales to handle any message volume. Use it for cloud-based applications prioritizing simplicity over advanced features.

API Gateway

The Problem

A mobile app talks to 12 microservices: User Service, Order Service, Payment Service, Inventory Service, Notification Service, and more. Each service has a different authentication method. The mobile app manages 12 API endpoints, 12 authentication schemes, and 12 retry strategies. Code becomes complex.

Loading the home screen requires calling 5 services: Users, Products, Recommendations, Cart, and Notifications. The mobile app makes 5 sequential HTTP requests. Total latency: 500ms. Users experience slow load times.

A malicious user sends 10,000 requests per second to the Order Service. No rate limiting exists. The service crashes. Legitimate users can't place orders.

API Gateways solve these problems by sitting between clients and microservices. Clients call one endpoint. The gateway routes requests to appropriate services, handles authentication uniformly, enforces rate limits, and aggregates multiple backend calls.

How API Gateways Work

Clients send all requests to the gateway at https://api.example.com. The gateway inspects the request path and method. GET /users/123 routes to User Service. POST /orders routes to Order Service.

The gateway enforces cross-cutting concerns:

- Authentication: verify JWT tokens before forwarding requests

- Rate limiting: allow 100 requests per minute per user, return 429 if exceeded

- Caching: cache product details for 5 minutes to reduce backend load

Request aggregation combines multiple backend calls. The mobile app requests GET /home. The gateway calls User Service, Product Service, and Cart Service in parallel. It combines responses into one JSON payload and returns it to the app. One request replaces three.

Load balancing distributes requests across multiple instances. Three Order Service instances run. The gateway routes requests round-robin: instance 1, instance 2, instance 3, instance 1...

Centralized logging tracks all API traffic. The gateway records request timestamps, response times, and error rates. This simplifies monitoring and debugging.

For detailed coverage of API gateway patterns, authentication strategies, and rate limiting implementations, see API Design and Gateway Patterns.

Common Implementations

AWS API Gateway is fully managed and integrates with Lambda, DynamoDB, and other AWS services. It handles authentication, throttling, and caching automatically. Use it for serverless applications or AWS-centric architectures.

Kong is an open-source gateway built on NGINX. It offers a plugin system for custom authentication, rate limiting, and transformations. Use it for self-hosted environments requiring flexibility and extensibility.

NGINX Plus combines reverse proxy with API gateway features. It delivers high performance and low latency. Use it for high-throughput applications where you need fine-grained control over routing and caching.

Problem Decomposition Framework

System design problems often arrive as vague statements: "Design Twitter" or "Design Uber." The first challenge is decomposing these into concrete technical requirements. Instead of guessing what the interviewer wants, use keywords in the problem statement as anchors.

The framework has three steps, each extracting different information from the problem description.

Step 0: Verbs → Use Cases

Verbs reveal operations. "Users can post tweets" contains the verb "post." "Users view their feed" contains "view." Extract all verbs to identify use cases.

Common verbs map to CRUD operations: create, read, update, delete, search, notify, process. Each verb becomes a functional requirement.

Beyond identifying operations, define what "correct" means for each. Does "post tweet" require deduplication? Should followers see tweets immediately or eventually? Must tweets persist forever? These questions transform vague verbs into precise contracts.

Step 1: Nouns → Entities and Ownership

Nouns reveal data models. "Users post tweets" contains two nouns: "users" and "tweets." "Users follow other users" reveals a relationship entity.

List all entities and their relationships. For each entity, identify the source of truth. Who owns user profile data? Where do tweets live? Which service controls the follow relationship?

Ownership matters because it determines write authority. Only the User Service updates user profiles. Only the Tweet Service creates tweets. Clear ownership prevents conflicting writes and establishes consistency boundaries.

Step 2: Adjectives → Constraints and Add-ons

Adjectives reveal non-functional requirements that force architectural choices. "Instant notifications" contains "instant"—this requires real-time push mechanisms or precomputation. "Highly available feed" contains "highly available"—this requires replication and stateless services.

Common adjectives and their implications:

instant/realtime → push notifications, WebSockets, caching, precomputation

reliable → retries, idempotency, dead letter queues, write-ahead logs

highly available → replication, stateless services, health checks

auditable/secure → encryption, access control, audit logs, compliance

scalable → partitioning, read replicas, message queues, horizontal scaling

Each adjective adds components to your architecture. The goal is not cramming in every technology. The goal is justifying each addition by tying it back to a specific constraint.

Interview Step-by-Step

Success in system design interviews requires structured approaches. This section demonstrates the process by solving Design Twitter, a popular system design problem using the decomposition framework.

Step 0: Identify Use Cases from Verbs

Apply the first step of the decomposition framework. Extract verbs from the problem statement to identify operations.

The problem is "Design Twitter." What can users do? Users post tweets. Users view their feed. Users follow other users. Users like tweets. Users comment on tweets.

Extract the verbs: post, view, follow, like, comment. Each verb maps to a use case:

- Post: create a new tweet

- View: read individual tweets or feeds

- Follow: create a relationship between users

- Like: increment engagement counter on a tweet

- Comment: create a response attached to a tweet

Now define what "correct" means. Should the same tweet content posted twice create two separate tweets or deduplicate? Interviews assume no deduplication unless specified. Should followers see new tweets immediately? This depends on non-functional requirements covered in Step 2. Must deleted tweets be recoverable? Not required for this problem.

Interviews last 45-60 minutes. Focus on core operations. Covering five use cases is sufficient.

Step 1: Identify Entities from Nouns

Apply the second step. Extract nouns from the use cases to identify entities and their relationships.

From "users post tweets," we get User and Tweet. From "users follow other users," we get a Follow relationship. From "users like tweets" and "users comment on tweets," we get Like and Comment (both are types of engagement).

List the entities:

- User: represents an account with profile information

- Tweet: represents a message with content, timestamp, and author

- Follow: represents the relationship between follower and followee

- Engagement: represents interactions (likes and comments) on tweets

For each entity, establish ownership:

- User entity: owned by User Service, stored in User Database

- Tweet entity: owned by Tweet Service, stored in Tweet Database

- Follow entity: owned by Follow Service, stored in Follow Database

- Engagement entity: owned by Engagement Service, stored in Engagement Database

Clear ownership prevents conflicts. If two services try updating the same tweet, which write wins? Establishing the Tweet Service as the single source of truth eliminates ambiguity.

Step 2: Identify Constraints from Adjectives

Apply the third step. Extract adjectives from the problem description to identify non-functional requirements and their architectural implications.

The problem states Twitter should have "low latency" responses, "high availability," support "scalable" growth, and ensure "durable" storage. Extract the adjectives: low latency, highly available, scalable, durable.

Map each adjective to technical solutions:

Low latency: Users expect feeds to load in under 500ms. This forces caching strategies. Precompute feeds and store in Redis. Read from cache instead of querying the database for every request.

Highly available: The system must handle partial failures. If the Tweet Service crashes after receiving a post request, the tweet should not be lost. This forces message queues. Buffer write requests in Kafka. Even if services go down, messages persist and process when services recover.

Scalable: Twitter has 400 million monthly active users. A single server cannot handle this load. This forces horizontal scaling with load balancers distributing requests across multiple service instances. It also forces database partitioning to distribute data across shards.

Durable: Tweets must never be lost. This forces distributed databases with replication. Store data across multiple nodes. If one node fails, replicas ensure data remains accessible.

Each adjective added components to the architecture. Without "low latency," we wouldn't need cache. Without "highly available," we wouldn't need message queues. The constraints drive the design.

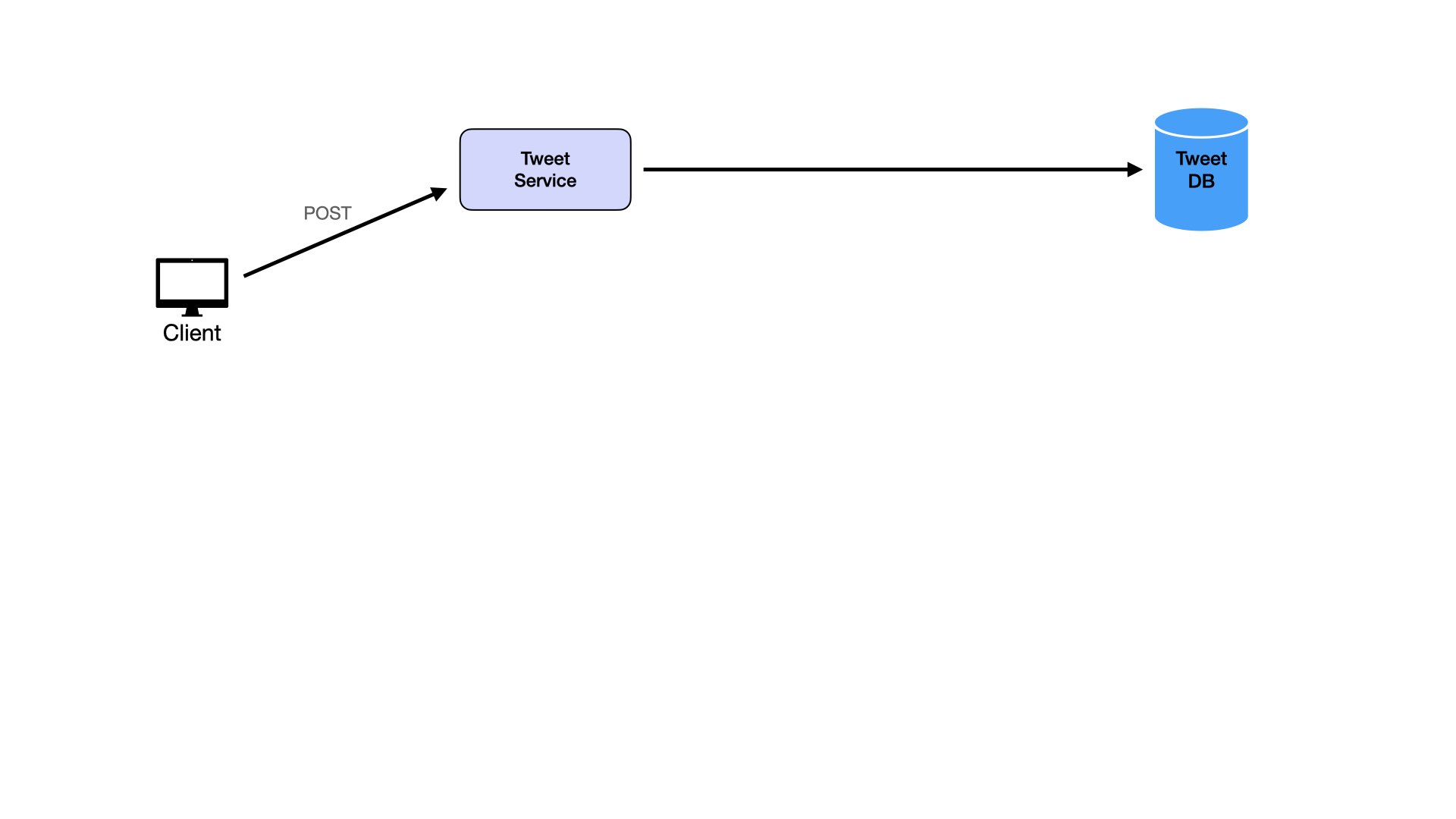

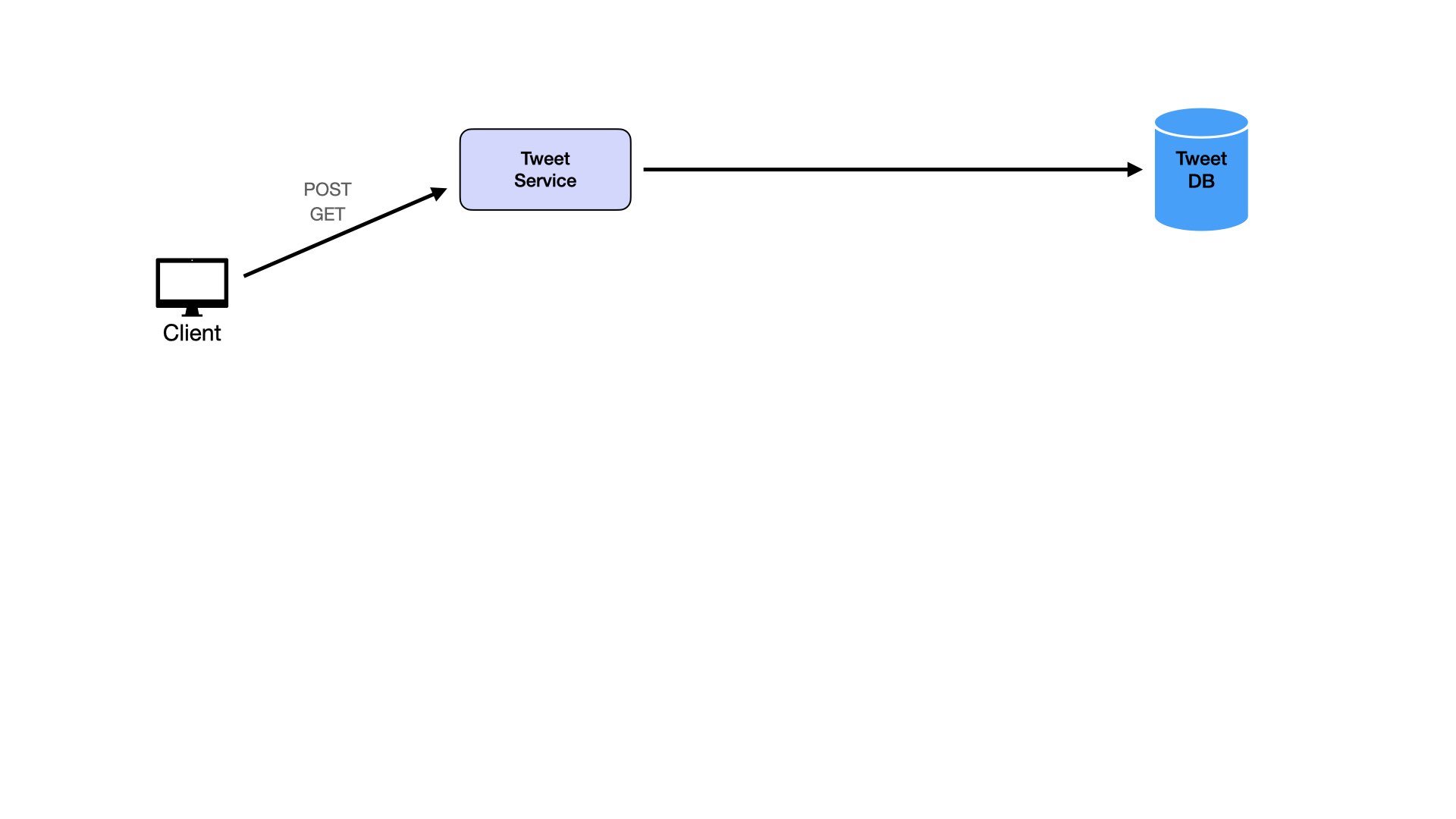

API Design

After defining requirements, design APIs. This stage takes a few minutes.

Many people overcomplicate this. Turn functional requirements into API endpoints. One endpoint per functional requirement.

Interviewers look for readable paths (easily understandable names like /tweet not /item), data types (know what data sends and receives with each API), and HTTP methods (POST for creating, GET for fetching).

For Twitter:

Users post tweets:

POST /tweet

Request

{

"user_id": "string",

"content": "string"

}

Response

{

"tweet_id": "string",

"status": "string"

}

Users view individual tweets:

GET /tweet/<id>

Response

{

"tweet_id": "string",

"user_id": "string",

"content": "string",

"likes": "integer",

"comments": "integer"

}

Users view feeds:

GET /feed

Response

[

{

"tweet_id": "string",

"user_id": "string",

"content": "string",

"likes": "integer",

"comments": "integer"

}

]

Users follow other users:

POST /follow

Request

{

"follower_id": "string",

"followee_id": "string"

}

Response

{

"status": "string"

}

Users like tweets:

POST /tweet/like

Request

{

"tweet_id": "string",

"user_id": "string"

}

Response

{

"status": "string"

}

Users comment on tweets:

POST /tweet/comment

Request

{

"tweet_id": "string",

"user_id": "string",

"comment": "string"

}

Response

{

"comment_id": "string",

"status": "string"

}

High-Level Design

High-level design is the bulk of the interview. Combine work from earlier steps with system design knowledge. This takes around 15-20 minutes but varies by level. Juniors spend more time here. Seniors move to deep dives more quickly.

We identified use cases (Step 0), entities (Step 1), and constraints (Step 2). Now build the architecture. Start with basic data flow supporting the use cases. Then layer in components addressing each constraint.

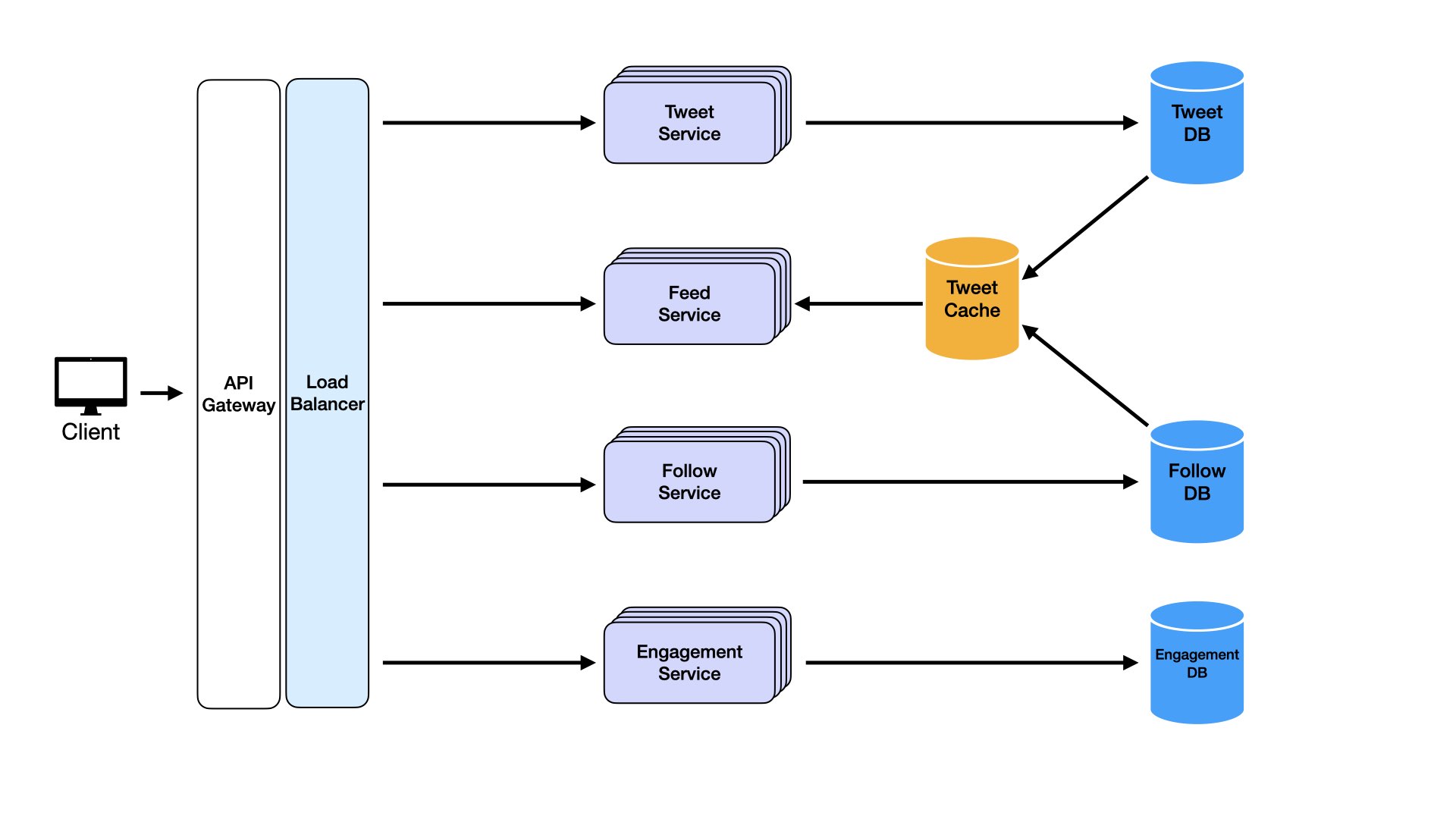

Basic Data Flow

Take API endpoints and map data flow with services. Show methodical, structured thinking. Start simple without complicated parts. This way, if you make mistakes, interviewers can correct them early.

For microservices approaches, see Microservices and Monolithic Architecture.

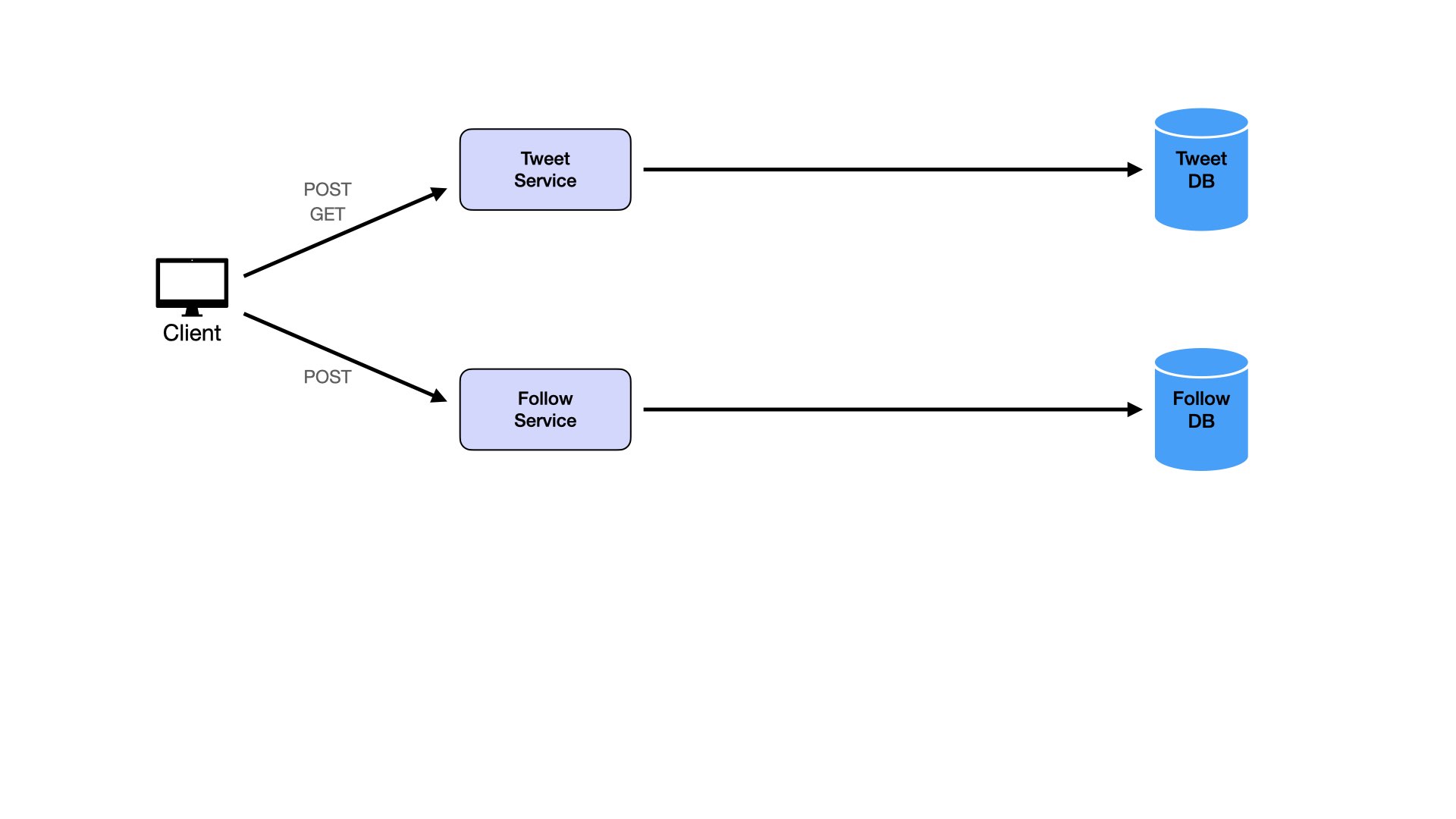

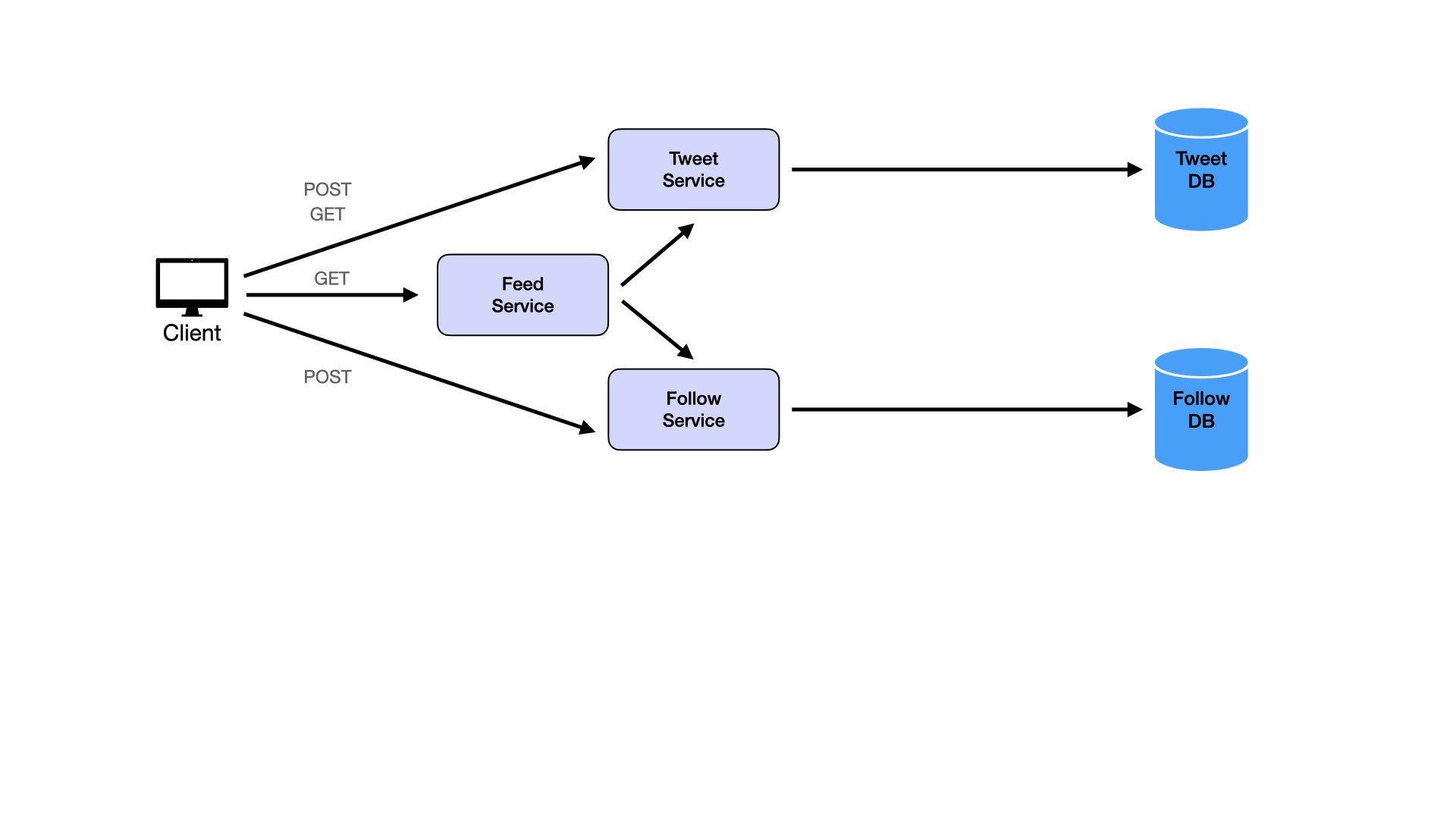

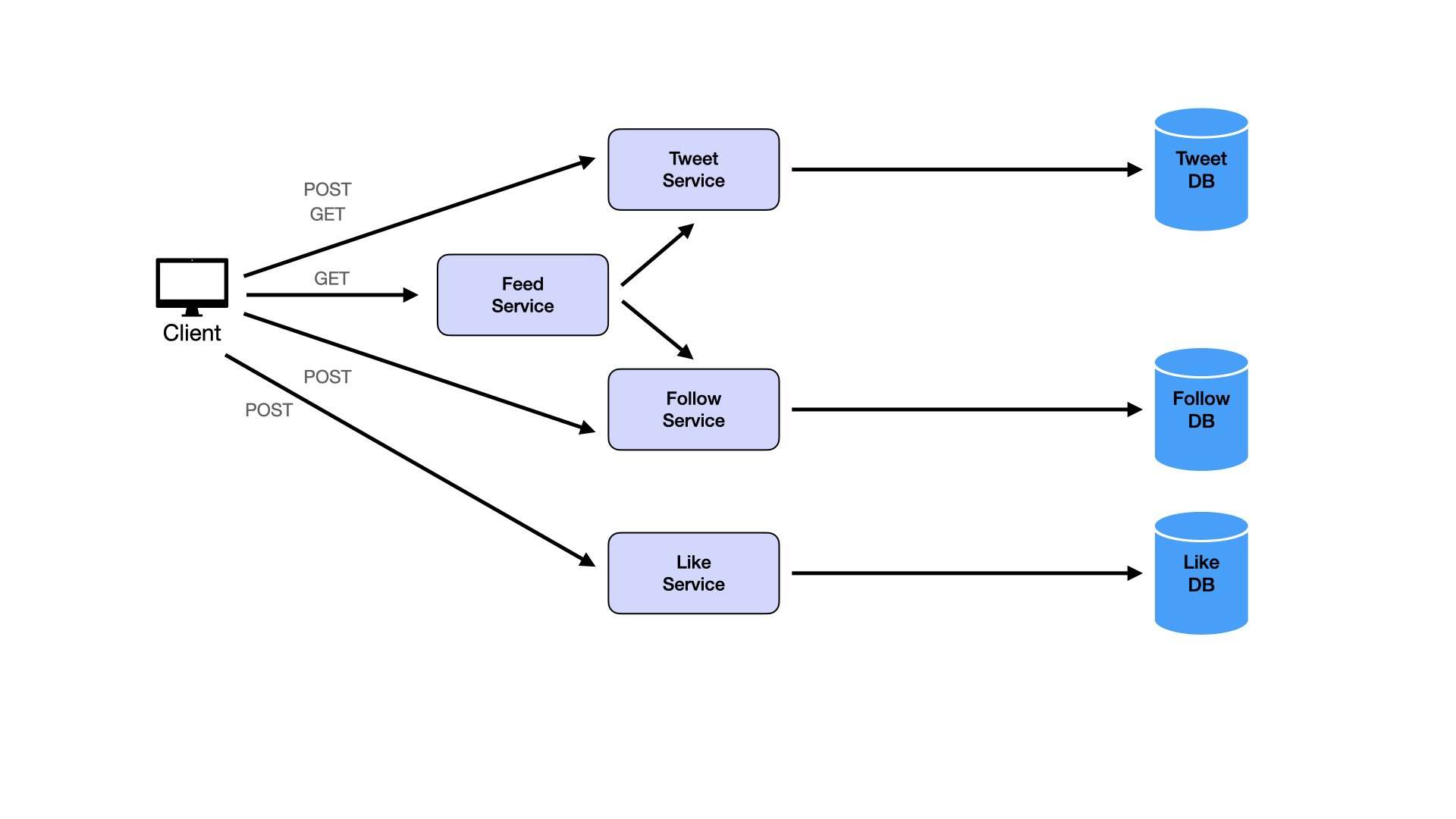

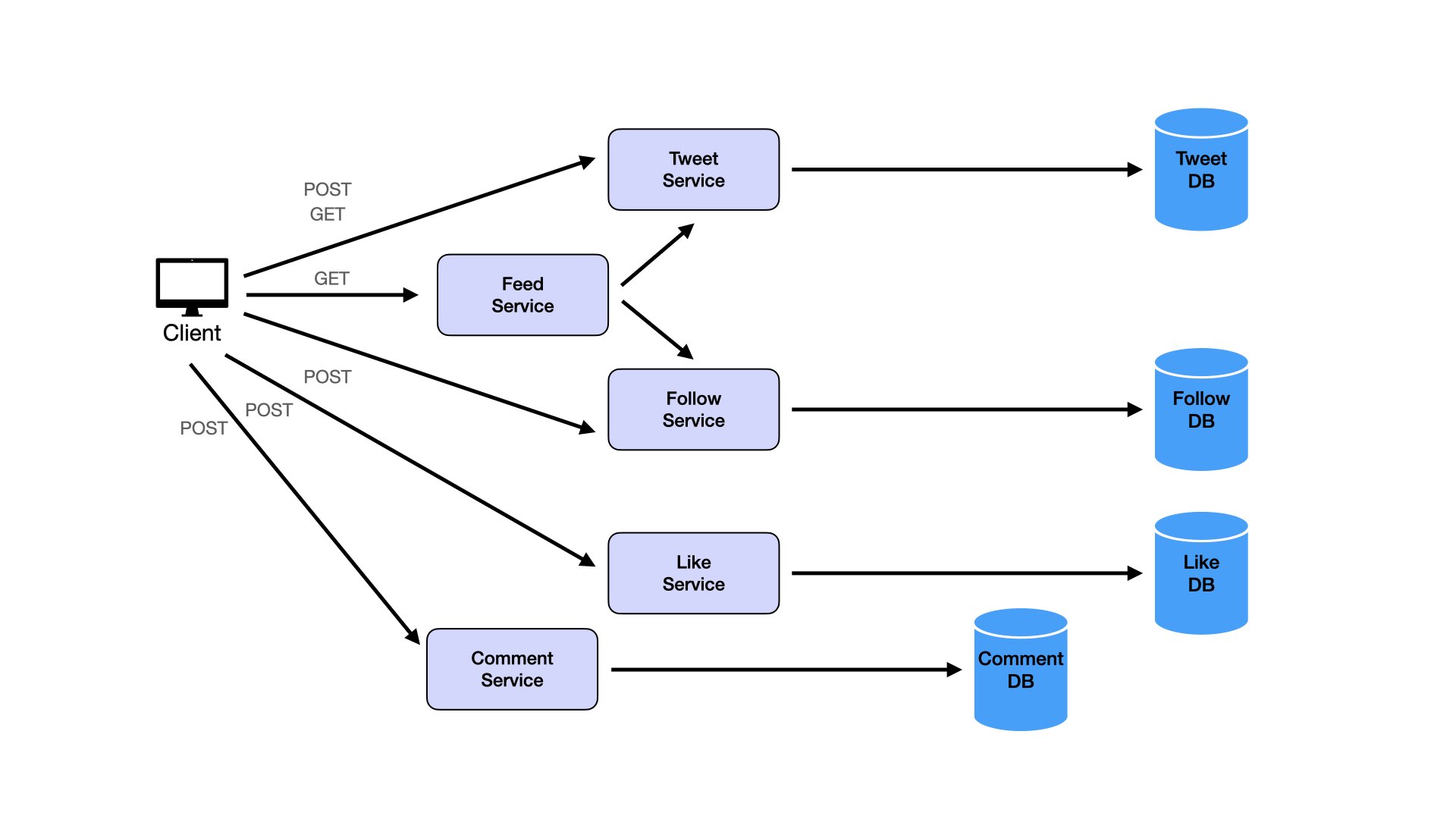

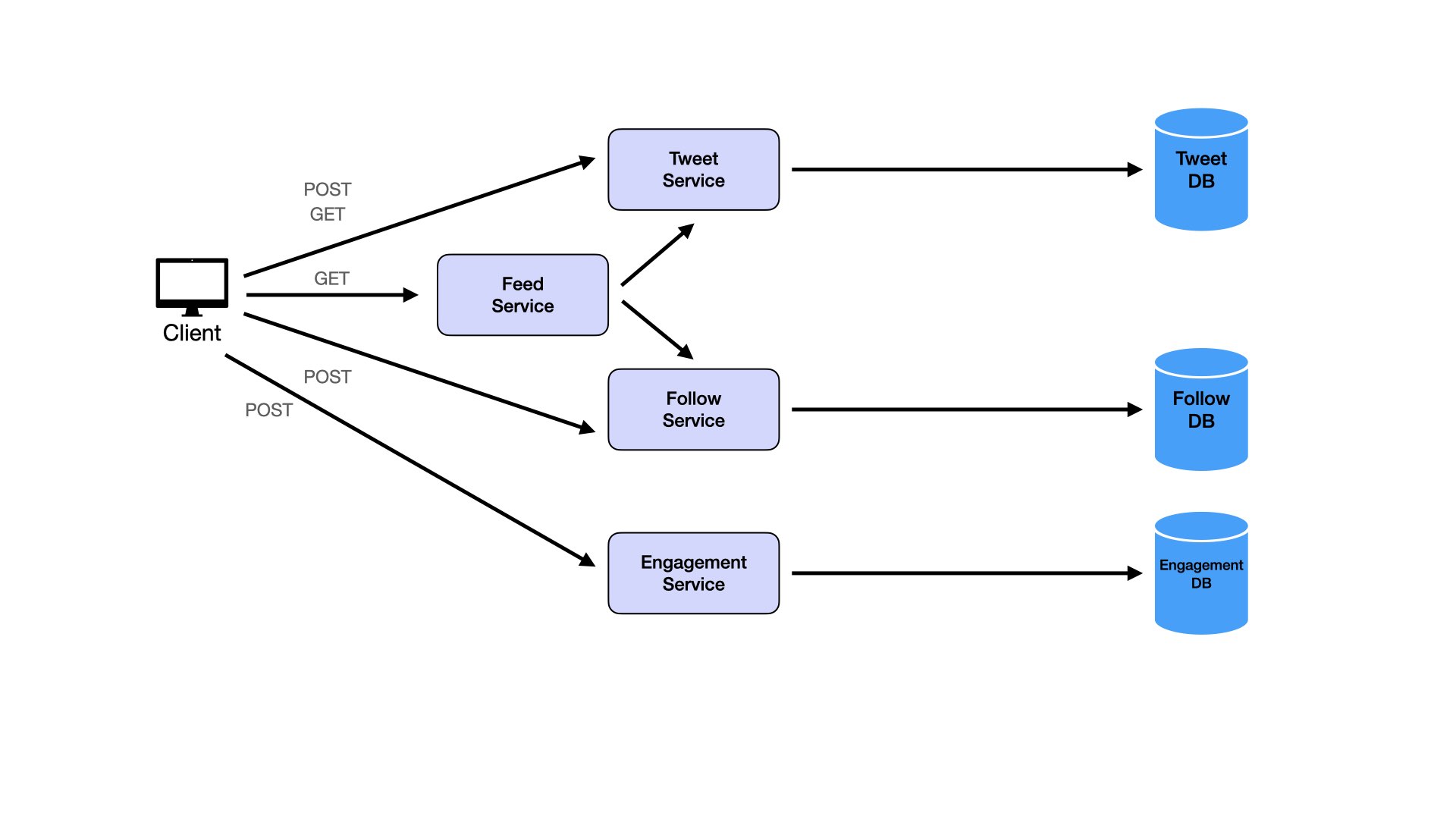

For Twitter:

Users post tweets:

Users view individual tweets:

Users follow other users:

Users view feeds:

Users like tweets:

Users comment on tweets:

This creates many services. Even though separation of concerns matters, avoid turning everything into microservices. Consider combining services. Likes and comments are logically similar. Both are ways of engaging with tweets. Both are types of counters on tweets with different data. This similarity suggests merging them into a single Engagement Service and Engagement Database.

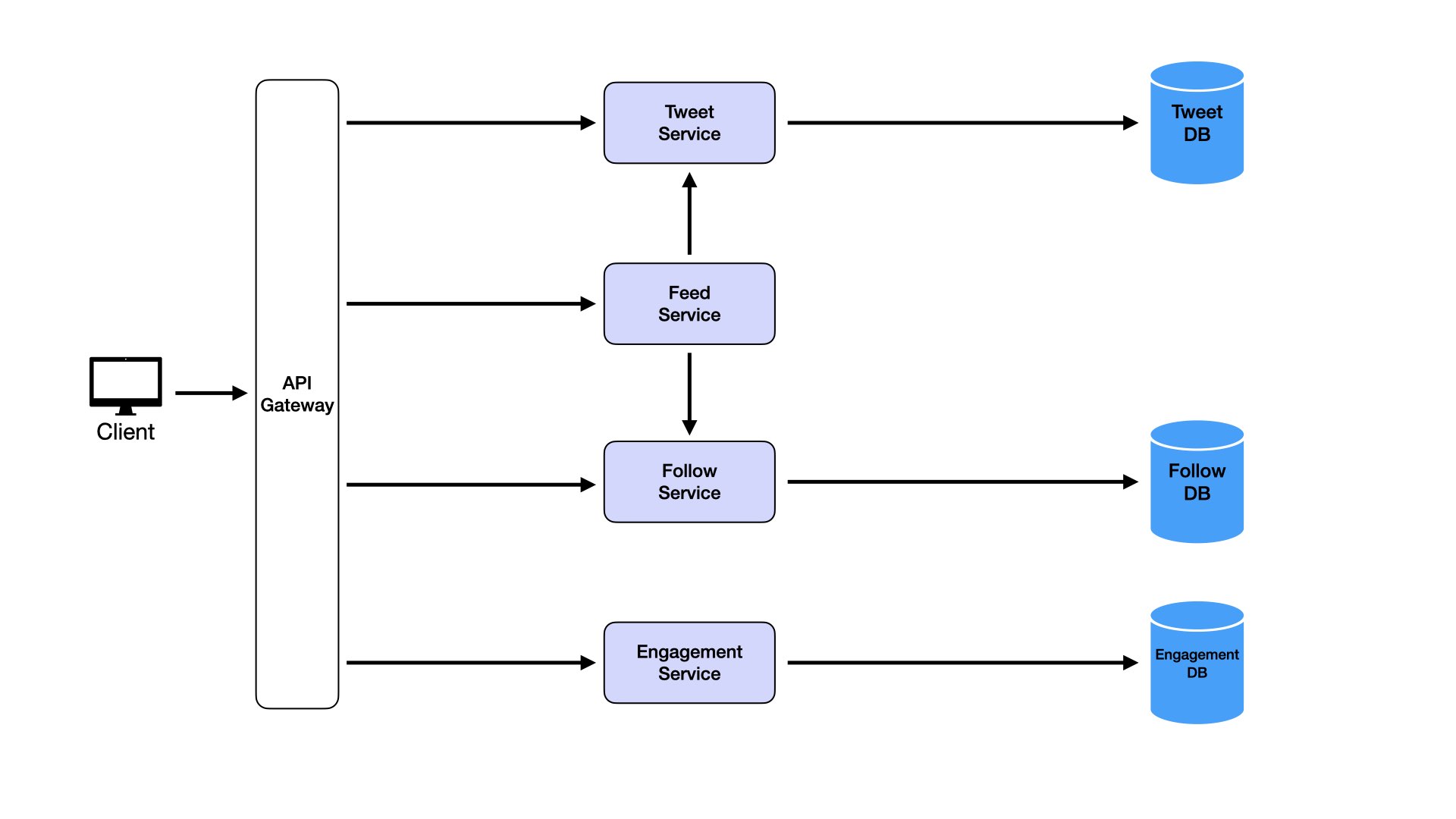

With multiple services, add an API gateway (see Main Components section above).

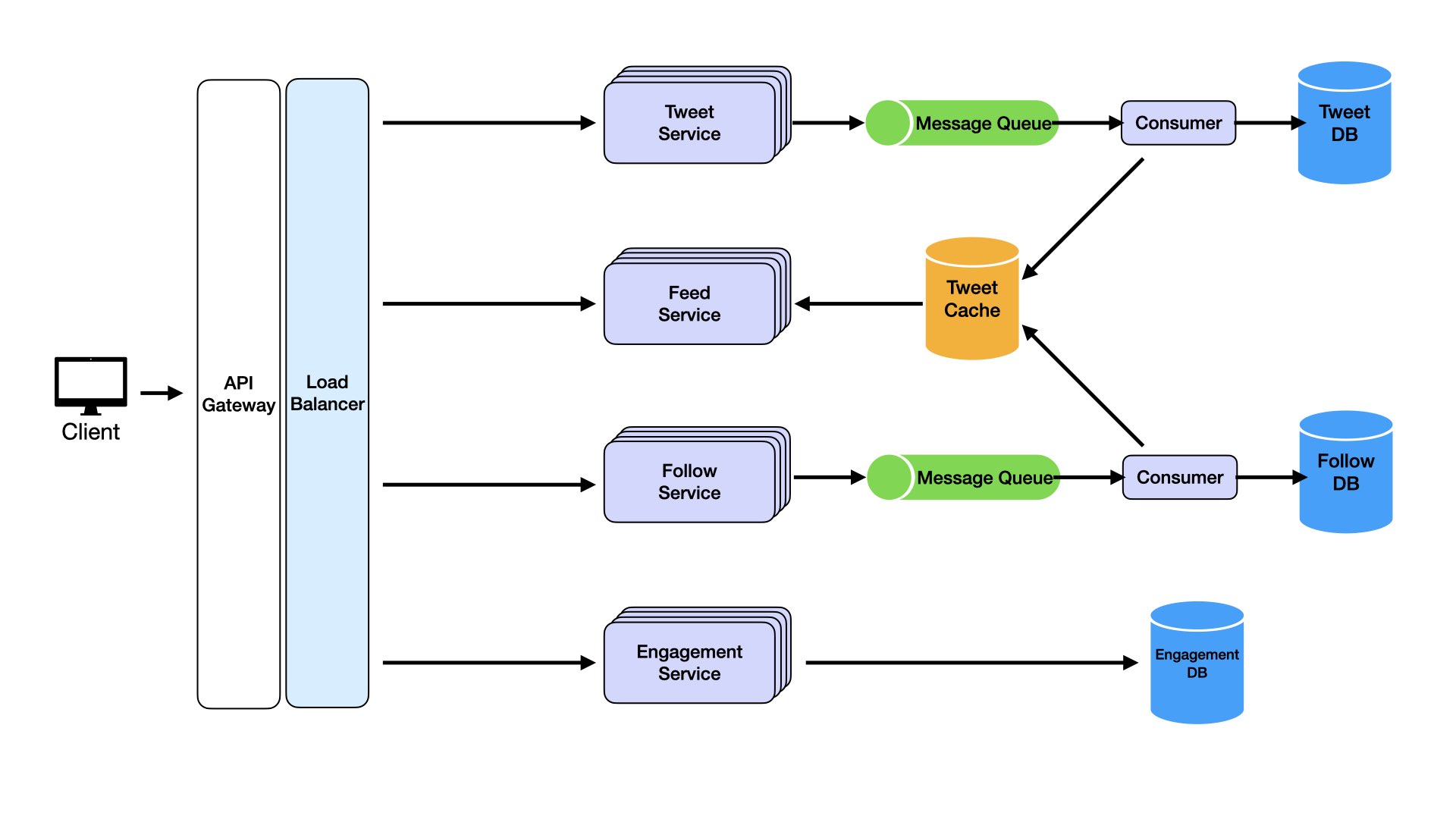

Applying Constraints

We have basic data flow supporting the use cases. This system works but fails at scale. Now apply the constraints identified in Step 2.

We identified four constraints: low latency, high availability, scalability, and durability. Address each constraint by adding the corresponding components. The biggest candidate mistake is adding components without justifying them.

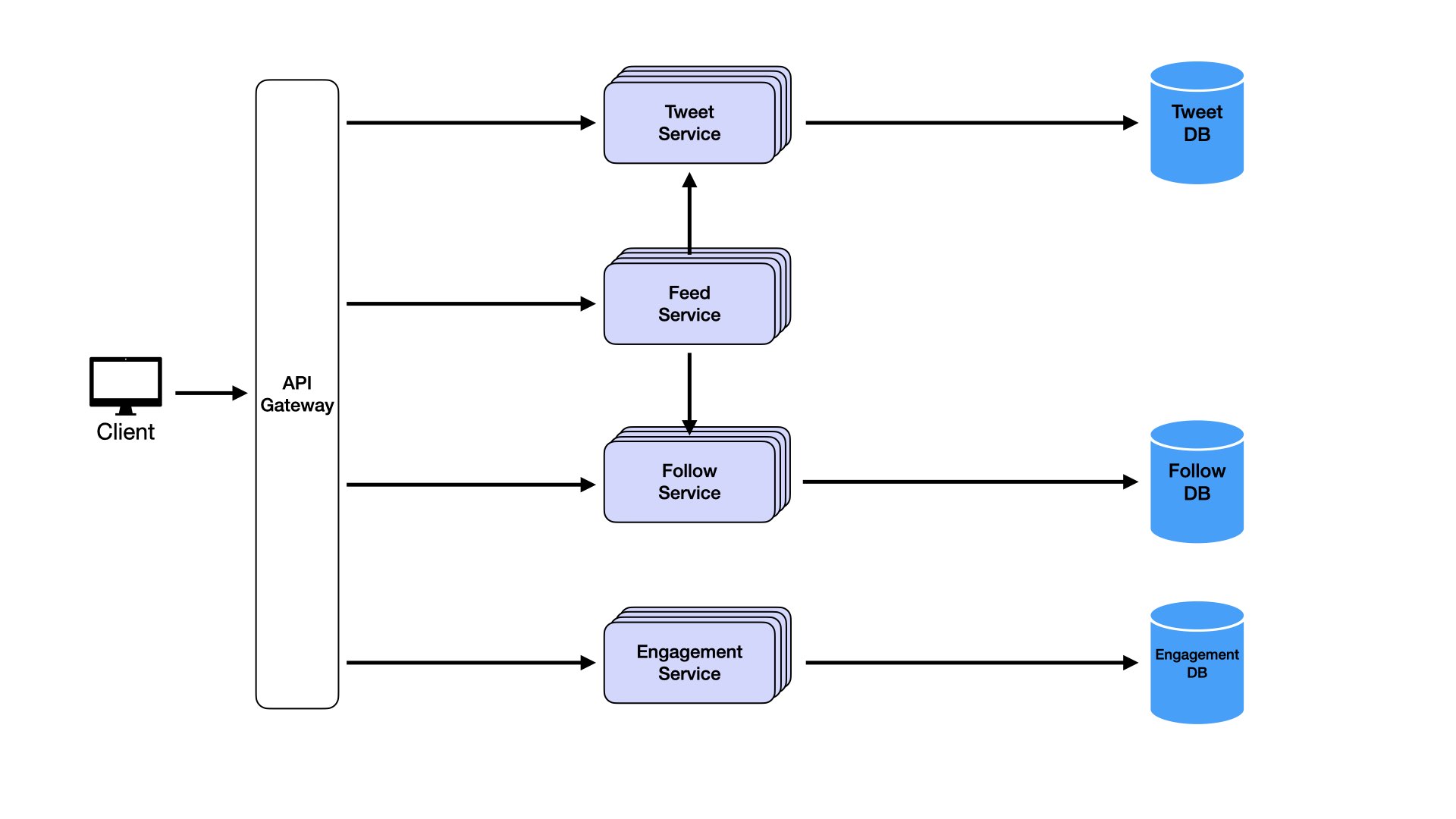

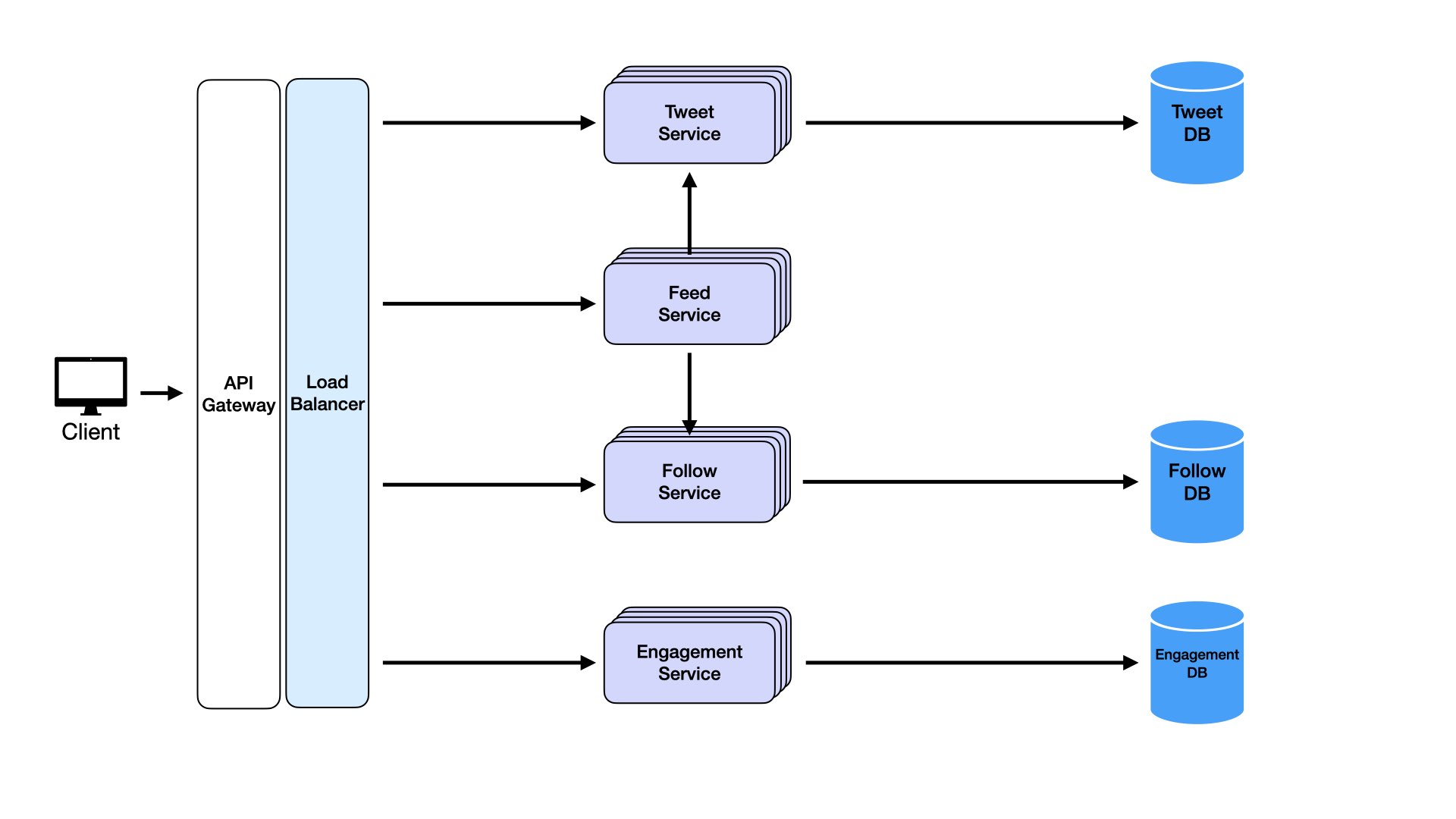

Start with scalability. This is relatively straightforward to address. Our goal is supporting horizontal scaling to handle user base growth and increased traffic seamlessly. Horizontal scaling adds more service instances to handle higher loads, ensuring consistent performance as demand increases.

Deploy multiple instances of each service: Tweet Service, Feed Service, Follow Service, and Engagement Service. These instances operate independently, handling requests in parallel. To distribute traffic efficiently across instances, add a load balancer.

A load balancer ensures incoming requests distribute evenly across available service instances. It performs health checks monitoring each instance's status and reroutes traffic away from unhealthy instances, ensuring high availability. This addresses another non-functional requirement and is a bonus from the load balancer. Scale each service dynamically based on traffic patterns. During peak hours, spin up more Feed Service instances to handle request surges, then scale back during lower activity to optimize resource usage.

Move to another core non-functional requirement: low latency. With few users posting tweets, servers run fast. Each user's feed fetches a handful of tweets. As we scale to millions of users and billions of tweets, accessing the database for every feed request becomes exponentially slow. Users writing tweets to the database, then feeds re-pulling these from the database each time is redundant.

Caches solve this.

A cache is high-speed data storage storing frequently accessed data closer to applications. The Feed Service could leverage distributed caching like Redis or Memcached to store recent tweets for each user.

When users post tweets, the Feed Service doesn't just update followers' feeds in the database. It also pushes new tweets to cache, storing them as part of precomputed feeds for followers. When followers log in, the Feed Service fetches feed data directly from cache instead of querying the database or relying on real-time aggregation.

Caches are ideal for storing hot data: data accessed frequently, like latest tweets for user feeds. Since caches operate in memory, they deliver data in milliseconds, reducing response times and improving user experiences.

By offloading repeated reads to cache, we reduce database load. This makes systems more scalable and ensures databases are available for other critical write operations.

To ensure cache stays fresh, set expiry times for cached items or use event-driven update models. When new tweets post, events trigger cache updates, ensuring followers see latest tweets without delays.

When adding load balancers earlier, we touched on how health checks help maintain high availability. But what else maintains high availability? Consider a situation where we might not have availability with the current system. A user posts a tweet at 1:02pm. At 1:03pm, the tweet service goes down. At 1:04pm, their followers log onto the app. Are followers going to see this tweet in their feed? No. Another scenario: millions of active users publish tweets simultaneously. Trying to process them all simultaneously would overload servers. Message queues solve this.

A message queue acts as a buffer between services, decoupling dependencies and ensuring messages (like new tweets) aren't lost even if services experience downtime. When users post tweets, the Tweet Service doesn't directly communicate with the Feed Service. Instead, it places tweets in a queue. Consumers process the queue and add to both database and cache. The Feed Service, which processes tweets to update user feeds, reads from this cache. Even if the Tweet Service goes offline, messages (tweets) are safely stored in the queue and processed by consumers. The Feed Service can still update followers' feeds when they log in.

Incorporating message queues ensures eventual consistency and high availability during partial system failures. In our scenario, followers would still see tweets in feeds thanks to queues ensuring no message loss. Decoupling services also helps scalability. Queues handle varying workloads and traffic spikes without overwhelming downstream services. Message queues like RabbitMQ, Kafka, or AWS SQS are built for durability and reliability, making them perfect for our use case.

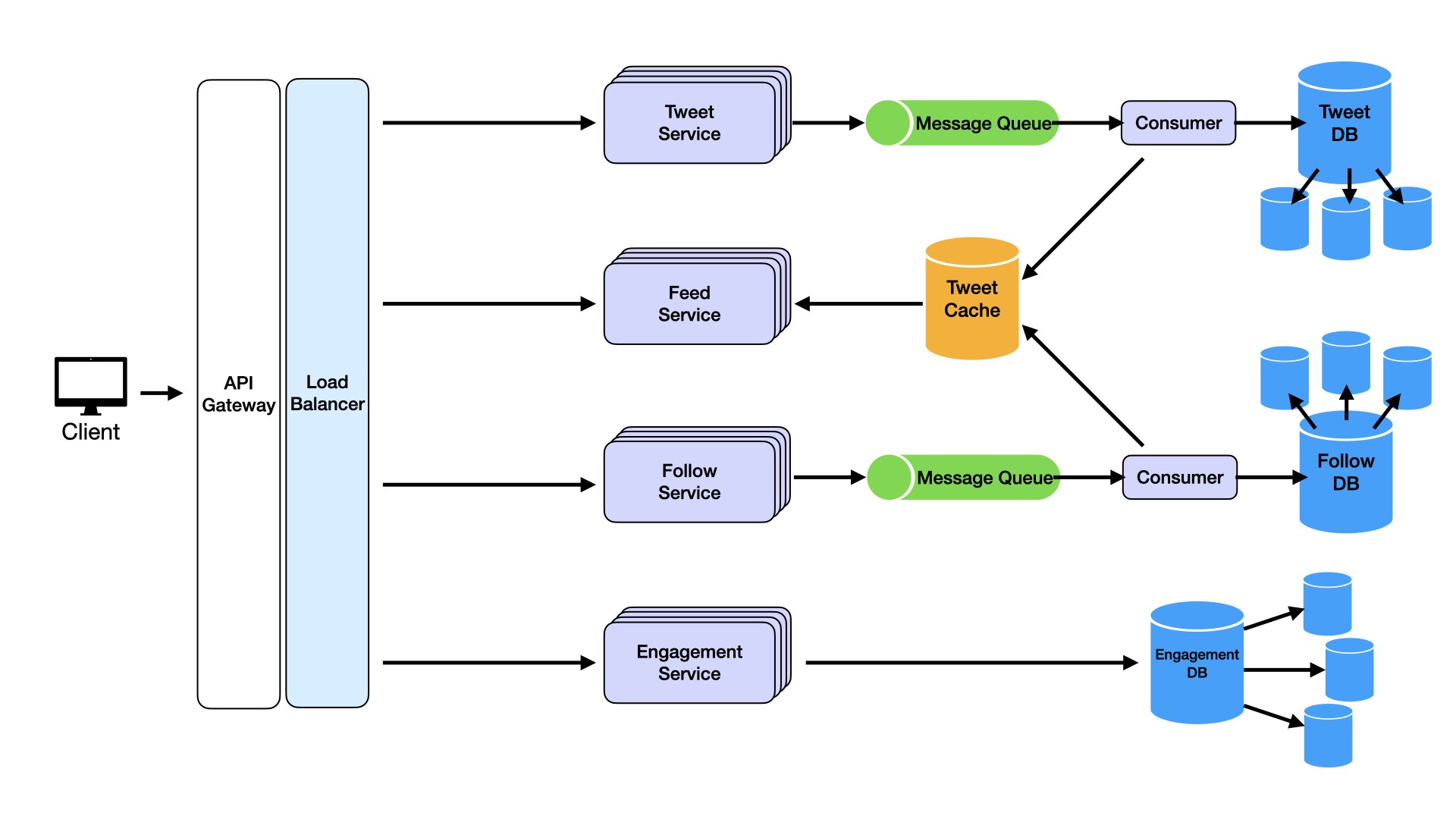

We've addressed service non-functional requirements. One last critical requirement remains: data durability. In systems handling billions of tweets, likes, and follows, ensuring data is never lost is essential. Once lost, we cannot recover it. How do we prevent this? Use distributed databases.

Distributed databases replicate and store data across multiple cluster nodes. Distributed databases like Amazon DynamoDB, Google Cloud Spanner, or Cassandra automatically replicate data across multiple nodes. Even if one node goes down, data remains accessible from other replicas. Additionally, distributed databases provide built-in mechanisms for point-in-time recovery and automated backups. Regular snapshots of Tweet DB, Follow DB, and Engagement DB can be taken and stored in separate backup systems. If complete failure occurs, data can be restored to its last consistent state.

Deep Dives

Deep dives are the last step of system design interviews. They focus on addressing higher-level, more specific challenges or edge cases in your system. They go beyond high-level architecture to test understanding of advanced features, domain-specific scenarios, and trade-offs.

How would you handle the Celebrity Problem?

The celebrity problem arises when users with millions of followers post tweets, creating massive fan-out as their tweets need adding to millions of follower feeds. This can overwhelm systems leading to latency and high write amplification.

Modify existing architecture to handle this efficiently. For normal users with manageable follower numbers, continue with standard fan-out-on-write. Tweets push to followers' feeds as soon as posted.

For users with large follower counts (more than 10,000), switch to fan-out-on-read. Celebrity tweets store in Tweet Database and Tweet Cache but aren't precomputed into individual follower feeds. When followers open feeds, the Feed Service dynamically fetches celebrity latest tweets from cache or database and merges them into user timelines.

Implement thresholds (follower count or engagement volume) to dynamically decide between fan-out-on-write or fan-out-on-read for given users.

How would you efficiently support Trends and Hashtags?

Twitter trends and hashtags involve aggregating data across billions of tweets in real-time to identify popular topics. How can we compute and update trends efficiently?

Enhance existing architecture. Each region or data center computes local trends by aggregating hashtags and keywords using sliding window algorithms (the past 15 minutes). Local results send to global aggregation services, which combine them to generate global trends.

Modify the Tweet Service to index hashtags upon tweet creation. Maintain inverted indexes where hashtags are keys and associated tweet IDs are values. Use distributed search engines like Elasticsearch or Solr to store and query hashtag indexes efficiently.

Trends calculate periodically (every minute) and cache in distributed caches like Redis for low-latency access. TTL (time-to-live) ensures trends refresh frequently without overwhelming systems.

How would you handle Tweet Search at Scale?

Search is a core Twitter feature, allowing users to search tweets, hashtags, and profiles. How can we support scalable, real-time search systems?

Incorporate distributed search architecture. Modify the Tweet Service to send newly created tweets to search indexing services via message queues. Indexing services process tweets and update search indexes in distributed search engines like Elasticsearch or Apache Solr.

Partition search indexes by time (daily indices) or hashtags to distribute load across multiple nodes. Older indices can store on slower storage systems to save costs while keeping recent indices on faster nodes.

Use inverted indexing for efficient keyword and hashtag search. Employ ranking algorithms (BM25 or ML-based) to surface most relevant tweets based on user engagement, recency, or other factors.

Cache popular search queries and results to reduce load on search engines.