Introduction

Uber is a ride-hailing service where a rider requests a ride, the system estimates the fare, finds nearby available drivers, and matches one to the rider. During the trip, the system tracks the driver's real-time location and streams updates to the rider's map. The trip moves through a lifecycle of states—searching, matched, in progress, completed—with each transition triggering side effects like notifications, fare metering, and payment.

The system handles millions of drivers sending persistent GPS coordinates every few seconds, performs sub-second geospatial searches to find the nearest driver, enforces unique driver assignment (no double-dispatch), and maintains durable, consistent trip records across the full ride lifecycle.

Functional Requirements

We extract verbs from the problem statement to identify core operations:

- "estimates the fare" and "calculates the route" → COMPUTE operation (Ride Pricing)

- "finds nearby drivers" and "matches one to the rider" → SEARCH + ASSIGN operation (Find and Match a Driver)

- "tracks the driver's location" and "streams updates" → INGEST + PUSH operation (Real-Time Tracking)

- "moves through a lifecycle of states" with side effects → STATE MACHINE operation (Trip Lifecycle)

Each verb maps to a functional requirement. Each requirement builds on the previous, progressively adding components to the architecture.

-

Rider enters a pickup location and destination. The system returns an estimated fare and ETA before the rider confirms the request.

-

After the rider confirms, the system finds nearby available drivers, ranks them, and assigns one through an offer/accept flow.

-

Online drivers continuously report GPS coordinates. During an active trip, the rider sees the driver's live position on a map in near real-time.

-

The system manages the full lifecycle of a trip through well-defined states, with each transition triggering appropriate side effects (notifications, metering, payment).

Scale Requirements

- Assume ~50 million daily active riders

- Assume ~5 million registered drivers, roughly 2 million online during peak hours

- Assume ~20 million trips per day

- Driver location updates roughly every 4–10 seconds when online (varies by trip state, OS battery throttling, and app settings). Assuming ~4s average during peak: 2M drivers / 4s = roughly 500,000 location writes per second

- Sub-5-second ride matching (rider expects to see a driver assigned within seconds)

- Real-time location tracking during trips (rider sees driver position update every few seconds)

Non-Functional Requirements

We extract adjectives and descriptive phrases from the problem statement to identify quality constraints:

- "real-time" location tracking → Low-latency updates; the rider must see the driver's position move smoothly on the map

- "millions of drivers" sending GPS "every few seconds" → High write throughput on location ingestion (the scale requirements estimate ~500K writes/sec at peak)

- "sub-second" geospatial searches → Fast nearby-driver lookup; this is the index query, separate from end-to-end matching which includes the offer/accept flow

- "unique" driver assignment (no double-dispatch) → Strict consistency on driver assignment, enforced via a single authoritative store per driver; under partitions, reject or queue rather than risk double-assignment

- "persistent" and "durable" trip records → Trip data and fare records must survive failures; state transitions must be atomic

- "consistent" trip lifecycle → Side effects (notifications, metering, payment) are triggered reliably (at-least-once) with idempotency/deduplication for effectively-once outcomes

Each adjective becomes a non-functional requirement that constrains our design choices. These NFRs imply: in-memory geospatial index for write-heavy location data, persistent WebSocket connections for real-time communication, and strong consistency on driver assignment operations.

- Low Latency: Sub-second geospatial lookup; end-to-end ride matching within 5 seconds (per scale requirements)

- High Throughput: Ingest ~500K location writes/sec at peak (per scale requirements); handle millions of trips per day

- Strong Consistency: A driver must never be double-assigned; trip state transitions must be atomic

- High Availability: Ride requests and tracking must stay up during peak hours; tolerate brief location staleness

Data Model

The data model is derived from extracting nouns in the problem statement:

- "rider" and "driver" → Trip entity linking both parties via rider_id and driver_id

- "fare" and "estimate" → Trip fields for estimated_fare and actual_fare

- "GPS coordinates" and "location" → DriverLocation entity for real-time tracking

- "trip lifecycle" and "states" → Trip.status field as the state machine

- "unique assignment" → Driver.version field for optimistic concurrency control

The Trip Service owns Trip records for consistency during state transitions. The Location Service owns the real-time geospatial index (in-memory) while a time-series database stores historical DriverLocation records asynchronously.

Trip

Core entity tracking a ride from request to completion. Each trip moves through states (SEARCHING, MATCHED, ARRIVED, IN_PROGRESS, COMPLETED, CANCELLED).

DriverLocation

Real-time GPS position of a driver. Updated every ~4 seconds. Stored in-memory for matching, persisted asynchronously for history.

Driver

Driver profile and current availability status. The version field supports optimistic concurrency for double-dispatch prevention.

Trip and Driver have a many-to-one relationship. A driver has many trips over time; each trip has at most one assigned driver.

Trip and DriverLocation have a one-to-many relationship. A trip's route is reconstructed from location snapshots. Persisted location records include a trip_id field (set during IN_PROGRESS state) to associate GPS points with a specific trip.

API Endpoints

We derive API endpoints directly from the functional requirements (verbs identified in Step 0):

- COMPUTE operation: "estimates the fare" → GET /rides/estimate (accepts coordinates, returns fare + ETA)

- CREATE operation: "requests a ride" → POST /rides (triggers driver matching)

- READ operation: "tracks the ride" → GET /rides/{id} (returns status + driver info)

- UPDATE operation: "sends GPS coordinates" → PUT /drivers/{id}/location (location updates; primarily sent over WebSocket, REST as fallback)

- ACTION operations: "accepts/declines offer" → POST /rides/{id}/offer/accept or decline

Each endpoint maps to a core operation. Most real-time communication happens over WebSocket, but the API defines the REST surface for ride operations.

/rides/estimate?pickup_lat={lat}&pickup_lng={lng}&dest_lat={lat}&dest_lng={lng}Get fare estimate and ETA before requesting. Returns estimated fare, distance, and duration based on routing.

/ridesConfirm and request a ride. Triggers driver matching. Returns ride ID for tracking.

/rides/{id}Get ride status, driver info, and ETA. Used for initial load; live updates come via WebSocket.

/rides/{id}/cancelCancel a ride. Cancellation rules depend on current state (free during SEARCHING, fee after MATCHED).

/drivers/{id}/locationUpdate driver GPS coordinates. Sent every ~4 seconds as a WebSocket message; this REST endpoint serves as an HTTP fallback.

/rides/{id}/offer/acceptDriver accepts a ride offer. Transitions ride to MATCHED and driver to en_route_to_pickup.

/rides/{id}/offer/declineDriver declines a ride offer. System tries next candidate driver.

/rides/{id}/ratingRate the ride after completion. Both rider and driver can rate.

High Level Design

1. Ride Pricing

Rider enters a pickup location and destination. The system returns an estimated fare and ETA before the rider confirms the request.

A rider opens the app, types "SFO Airport" as the destination, and sees "$24.50, ~23 min." This estimate appears before they commit to the ride. Let's build the pricing flow incrementally.

The Problem

Fare depends on the actual driving route, not the straight-line distance between two points. A 10km straight line might be 15km of road with turns, highway ramps, and one-way streets. Straight-line pricing would consistently undercharge for complex routes and overcharge for highway trips.

Step 1: Route Calculation via Routing Service

The Ride Service sends the pickup and destination coordinates to a Routing Service. The Routing Service models the road network as a weighted graph: intersections are nodes, road segments are edges, weights are expected travel times.

A shortest-path algorithm (Dijkstra or A* variant) finds the fastest route and returns the total distance and estimated duration. This calculation accounts for road types (highway vs residential), turn costs, and one-way restrictions.

Step 2: Fare Calculation

With the route distance and estimated duration, the Ride Service computes the fare:

fare = base_fare + (distance_km × per_km_rate) + (duration_min × per_min_rate)

If surge pricing is active in the pickup zone (see Staff-Level Discussions), multiply by the surge factor. The response includes the estimated fare, ETA, and surge multiplier so the rider can make an informed decision.

The rider sees the estimate and taps "Confirm." The system creates a ride request with status SEARCHING and begins the matching process described in the next requirement.

The architecture at this stage is straightforward: the Rider App sends a fare estimate request through the API Gateway to the Ride Service. The Ride Service calls the Routing Service for route distance and duration, computes the fare, and stores the trip record in the Trip DB. Two services, one database—this is the starting point we'll build on.

2. Find and Match a Driver

After the rider confirms, the system finds nearby available drivers, ranks them, and assigns one through an offer/accept flow.

The rider confirmed the ride. The system needs to answer: "Which available drivers are near this rider?" and assign the best one. Let's build this incrementally.

The Problem

The naive approach queries the driver database directly:

SELECT * FROM drivers

WHERE status = 'available'

AND distance(lat, lng, 37.77, -122.41) < 3000

ORDER BY distance

LIMIT 5;With 2 million online drivers and no spatial index, this query calculates distance for every row. Standard B-tree indexes on latitude or longitude alone don't help—they narrow one dimension but still scan thousands of candidates in the other. At 1,000 ride requests per second during peak, each full-scan query holds a connection for hundreds of milliseconds, exhausting the connection pool.

Step 1: Geospatial Index for Nearby Search

Instead of scanning all drivers, organize driver locations in a geospatial index that groups nearby drivers together. We use geohash-based spatial indexing: encode each driver's coordinates into a string where nearby locations share a common prefix.

When a rider requests a ride:

- Compute the rider's geohash at the search precision (e.g., precision 6, roughly ~1km-scale cells; exact dimensions vary by latitude)

- Query the rider's cell and all 8 neighboring cells—the 9-cell search pattern handles drivers near cell boundaries

- Filter to

availabledrivers only, and remove any beyond the maximum search radius using actual distance calculation - Rank remaining candidates by distance from the rider's pickup point

If the initial search returns too few candidates (common in suburban areas), expand to a coarser geohash precision (roughly 5km × 5km cells). Keep expanding until enough candidates are found or the maximum radius is reached.

Step 2: Send Offer and Match

With a ranked list of nearby available drivers, the Matching Service sends a ride offer to the nearest candidate via their WebSocket connection: "New ride request, pickup at X, destination Y. Accept?"

The driver has a timeout window (e.g., 15 seconds) to respond:

- Accept: The ride transitions to

MATCHED. The rider is notified with driver details and ETA. - Decline or timeout: The system tries the next candidate on the list.

If all candidates decline or time out, expand the search radius and try again. If no driver is found after all retries, notify the rider: "No drivers available. Try again shortly."

A critical correctness problem exists here: what if two ride requests simultaneously try to assign the same driver? This double-dispatch problem is covered in the Deep Dive section.

The architecture now adds three components. The Matching Service receives ride requests and queries the Geospatial Index (in-memory) for nearby available drivers. It sends ride offers to drivers through the Connection Service, which maintains WebSocket connections to Driver Apps. The Ride Service, Routing Service, and Trip DB from FR0 remain unchanged.

3. Real-Time Driver Tracking

Online drivers continuously report GPS coordinates. During an active trip, the rider sees the driver's live position on a map in near real-time.

The ride is matched. The rider is watching their phone, waiting for the driver's car icon to appear and move toward them. This requires two things: a pipeline to ingest driver GPS updates at massive scale, and a way to push those updates to the rider's device in real-time. Let's build both.

The Problem

Two million online drivers send GPS coordinates every 4 seconds. That's roughly 500,000 writes per second on average at peak—potentially bursty without client-side jitter, since timers can align after reconnection storms or OS scheduling. And during an active trip, each location update must reach the rider's phone within seconds. How do we communicate between driver and rider in real-time?

Step 1: WebSocket Connections

Both rider and driver apps maintain a persistent WebSocket connection to a Connection Service. WebSocket provides a bidirectional channel: the driver sends location updates upstream, and receives ride offers downstream. The rider sends ride requests upstream, and receives tracking updates downstream.

Step 2: Location Ingestion Pipeline

Every 4 seconds, each online driver's app sends a location update over their WebSocket connection: {driver_id, lat, lng, timestamp, heading, speed}. The Location Service receives these updates and does two things:

- Update the geospatial index — Compute the driver's geohash. Store the driver's position under that geohash key. If the driver moved to a new cell, remove from the old cell and add to the new one.

- Forward to active trip — If this driver is on an active trip, push the location to the rider (Step 3).

The geospatial index lives in memory. A single relational database table would struggle with 500,000 random writes per second—durable commits require WAL/fsync and index maintenance, making this volume impractical on a single node without heavy batching and sharding. An in-memory data store with geospatial commands handles this volume efficiently—typically low-millisecond latency per operation, depending on payload size and cluster configuration. To handle out-of-order GPS updates, the index applies a "latest-timestamp wins" rule per driver and drops stale updates.

For durability (trip history, analytics, dispute resolution), we persist location updates asynchronously. A message queue buffers updates; a consumer writes them to a time-series database in batches. The in-memory index is the real-time view; the persistent store is the historical record.

Step 3: Location Relay to Rider

When a driver's location update arrives and the driver is on an active trip, the Location Service forwards it to the rider. But the rider is connected to a different Connection Service instance. How does the Location Service know which instance?

A connection registry (an in-memory key-value store) maps user_id → connection_service_instance. When a client connects, the Connection Service registers the mapping with a short TTL and periodic heartbeats. The registry is sharded by user_id and replicated for availability. Any backend service that needs to push a message looks up the registry and routes the message to the correct instance.

The full flow: Driver app → Connection Service A → Location Service → [update index] → look up rider's connection → Connection Service B → rider's WebSocket → rider app renders position on map.

The rider sees the driver's position update every few seconds. The client interpolates between updates to produce smooth map animation. Active trips may use higher frequency updates during pickup approach.

Handling Disconnections

Mobile networks are unreliable. When a rider's WebSocket drops (tunnel, elevator), the system buffers recent events for each active trip. On reconnection, the client sends its last-seen event timestamp, and the server replays anything newer.

The architecture now adds four components. The Location Service receives GPS updates from the Connection Service and splits them into two paths: the hot path updates the in-memory Geospatial Index for real-time matching, while the cold path sends updates through a Message Queue to a Time-Series DB for durable history. To relay location to riders, the Location Service consults the Connection Registry to find which Connection Service instance holds the rider's WebSocket. All previous components (API Gateway, Ride Service, Matching Service) remain unchanged.

4. Trip Lifecycle Management

The system manages the full lifecycle of a trip through well-defined states, with each transition triggering appropriate side effects (notifications, metering, payment).

So far we've covered how the rider gets a fare estimate, how the system finds and matches a driver, and how location updates flow in real-time. Now we need to manage what happens after matching: the driver drives to the pickup, picks up the rider, drives to the destination, and completes the trip. Each phase has different rules and different data flowing to both parties.

The Problem

A ride involves many state changes: searching → matched → driver arrived → trip in progress → completed. Each transition triggers different side effects. When the driver is matched, the rider needs a notification with driver details. When the trip starts, fare metering begins. When it completes, payment is triggered. Without a formal state machine, these transitions become ad-hoc and error-prone—a missed notification, a fare that never starts metering, a payment that fires twice.

Step 1: Trip State Machine

A trip moves through these states:

- SEARCHING — Rider requested, system is finding a driver

- MATCHED — Driver assigned, en route to pickup location

- ARRIVED — Driver reached the pickup, waiting for rider

- IN_PROGRESS — Rider picked up, driving to destination

- COMPLETED — Arrived at destination, fare calculated

- CANCELLED — Cancelled by rider or driver (rules depend on current state)

Each transition is performed atomically in a single database transaction (conditional state update + outbox insert). The Trip Service validates that the transition is legal (e.g., you can't jump from SEARCHING to IN_PROGRESS) and updates the record. To reliably publish events after each transition, the service writes the event to an outbox table in the same database transaction as the state change. A separate process reads the outbox and publishes domain events (e.g., trip.matched, trip.started, trip.completed) to a message queue for downstream consumers. This avoids the dual-write problem where the DB update succeeds but the event publish fails.

Step 2: Transition Side Effects

Each state change triggers different actions:

- SEARCHING → MATCHED: Notify rider with driver details (name, car, ETA). Start streaming driver's location to rider. Notify driver with pickup location and navigation.

- MATCHED → ARRIVED: Notify rider "Your driver has arrived." Start a wait timer—if rider doesn't show within a configured window (e.g., 5 minutes, varies by market), driver can cancel.

- ARRIVED → IN_PROGRESS: Start metering the trip (distance and time tracking for fare calculation). Switch navigation to destination.

- IN_PROGRESS → COMPLETED: Calculate final fare from metered distance and time plus any surge multiplier. Trigger payment processing. Prompt both parties for ratings.

- Any → CANCELLED: Rules depend on current state. Cancelling during SEARCHING is free. Cancelling after MATCHED may incur a fee to compensate the driver. Cancelling during IN_PROGRESS involves partial fare calculation.

Idempotent Transitions

Network issues can cause duplicate transition requests. If the driver's app sends "arrived at pickup" twice due to a retry, the Trip Service handles this gracefully. Each transition checks the current state before applying. If the trip is already ARRIVED, a duplicate "arrived" request is a no-op. This makes state transitions idempotent—safe to retry without changing the state. Side effects (notifications, event emission) also need deduplication via idempotency keys or unique constraints in the outbox to prevent duplicate triggers.

Fare Estimation vs Actual Fare

The estimated fare (from FR0) uses expected route distance and time. The actual fare is calculated from metered distance and time after the trip completes. If the actual fare differs significantly (e.g., driver took a much longer route), the system can flag it for review or cap the fare at the estimate.

The final architecture adds three components. The Trip Service manages the state machine, writing each transition atomically to the Trip DB + Outbox. An outbox reader publishes domain events (trip.matched, trip.completed, etc.) to the Message Queue. Event Consumers subscribe and handle side effects: sending notifications, triggering payment, and updating analytics. This completes the architecture—all previous components from FR0 through FR2 remain, and the Trip Service ties them together through the state machine lifecycle.

Deep Dive Questions

How do you handle 500,000 driver location updates per second without overwhelming the database?

Two million online drivers, each sending GPS coordinates every 4 seconds. That's roughly 500,000 writes per second on average at peak, with spikes during rush hour. A relational database doing 500K durable random writes per second on a single table would struggle—WAL/fsync overhead, index maintenance, and transaction coordination make this impractical without heavy batching and sharding.

Separating Hot and Cold Paths

Here's the important realization: the geospatial index for real-time matching doesn't need durability. If it crashes, connected drivers will send new updates within a few seconds—though mobile network conditions, client reconnection delays, and backoff logic mean full recovery of a shard's data may take longer. Replication or replay from a recent snapshot helps close this gap. This means the real-time index can be purely in-memory, optimized for speed.

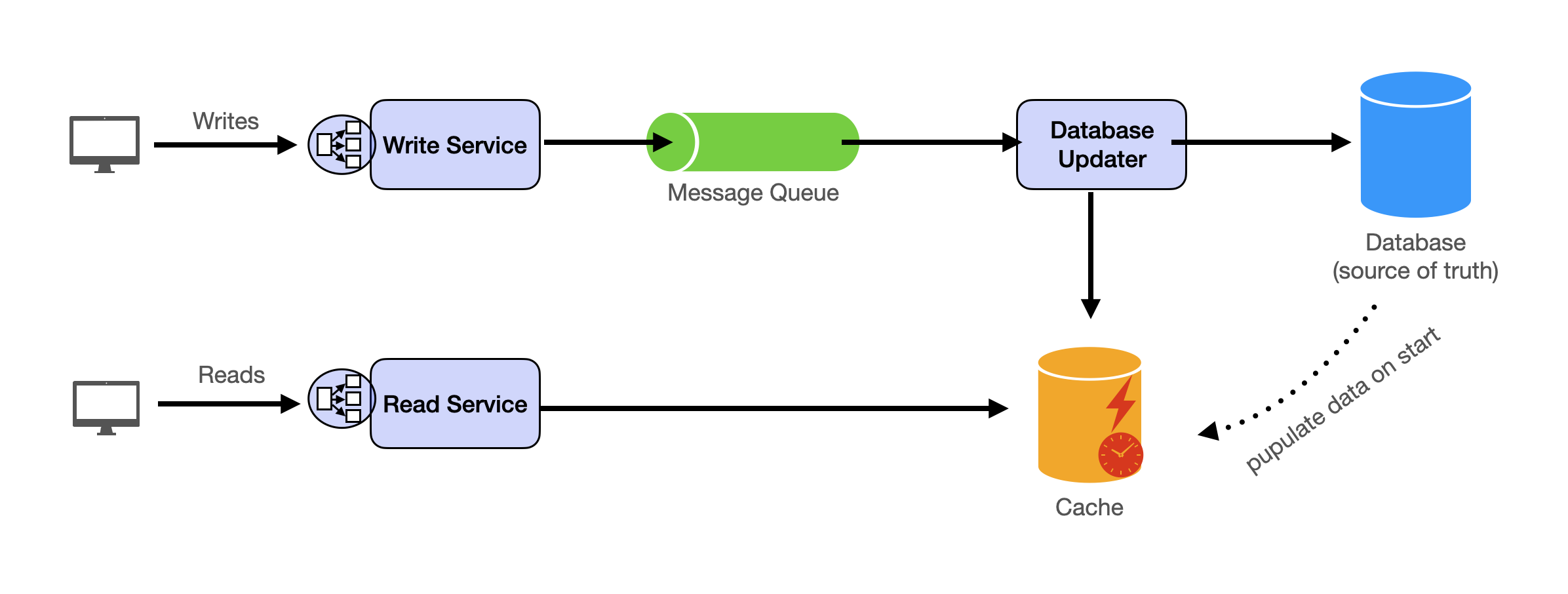

The durable record (for trip history, analytics, dispute resolution) can be written asynchronously. This splits the problem into two paths:

- Hot path: Driver → Location Service → in-memory geospatial index. Typically low-millisecond writes (depending on cluster configuration and replication settings). This is what matching queries read from.

- Cold path: Location Service → message queue → batch consumer → time-series database. Writes in batches of thousands. No strict sub-second requirement, but keep end-to-end lag bounded (seconds to minutes) for consumers like dispute resolution and safety audits.

The hot path handles the throughput challenge. The cold path handles the durability requirement. Neither needs to do both.

Sharding the Geospatial Index

Even in-memory, a single node handling 500K writes per second may hit CPU limits (each write involves computing a geohash and updating a sorted set). Shard the index by geographic region: North America, Europe, Asia, etc. Each shard handles drivers in its region only.

Within a region, further partition by city or metro area if needed. The sharding key is the driver's coarse geohash prefix (e.g., first 2-3 characters). Most proximity queries stay local to one shard. For riders near a shard boundary, the system queries the adjacent shard as well—this is handled by checking which shard owns each of the 9 neighboring cells and fanning out the query if needed.

Adaptive Update Frequency

Not all location updates are equally valuable. A driver parked at a rest stop doesn't need to report every 4 seconds—their position isn't changing. A driver approaching a pickup needs frequent updates.

Reduce reporting frequency when the driver is stationary or far from any ride request. Increase frequency during active trips or when the driver is near a rider's pickup. This can cut total update volume significantly without affecting matching quality.

Handling Stale Data

If a driver's app loses connectivity, their last-known position stays in the index. After a timeout (e.g., 30 seconds without an update), mark the driver as stale and exclude them from matching.

Rebuilding After Failure

If a geospatial index shard crashes, all drivers on that shard temporarily disappear from matching. Recovery options:

- Wait for drivers to re-report — within one or a few reporting intervals, connected drivers send new updates and re-populate the index. Simple, but creates a gap (longer under poor network conditions or reconnection backoff).

- Replay from the message queue — the cold path queue has recent updates. Replay the last 30 seconds to rebuild the index faster.

- Read replica — maintain a standby replica of each shard. On primary failure, promote the replica. Near-zero recovery time but doubles memory cost.

A common approach is replica promotion for fast failover, with client re-reporting as the natural steady-state recovery. Other deployments may rely primarily on replay from a message queue depending on cost and complexity constraints.

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.