Introduction

A URL Shortener is a service that takes a long URL and generates a shorter, unique alias that redirects users to the original URL. Popular examples include bit.ly, TinyURL, and Twitter's t.co.

This alias is often a fixed-length string of characters. The system should be able to handle millions of URLs, allowing users to create, store, and retrieve shortened URLs efficiently. Each shortened URL needs to be unique and persistent. Additionally, the service should be able to handle high traffic, with shortened URLs redirecting to the original links in near real-time. In some cases, the service may include analytics to track link usage, such as click counts and user locations.

Functional Requirements

We extract verbs from the problem statement to identify core operations:

- "takes a long URL and generates a shorter alias" → CREATE operation (URL Shortening)

- "redirects users to the original URL" → READ operation (URL Redirection)

- "track link usage" → UPDATE/INCREMENT operation (Analytics)

Each verb maps to a functional requirement that defines what the system must do.

-

Users should be able to input a long URL and receive a unique, shortened alias. The shortened URL should use a compact format with English letters and digits to save space and ensure uniqueness.

-

When users access a shortened URL, the service should redirect them seamlessly to the original URL with minimal delay.

-

The system should be able to track the number of times each shortened URL is accessed to provide insights into link usage.

Scale Requirements

- 100M Daily Active Users

- Read:write ratio = 100: 1

- Data retention for 5 years

- Assuming 1 million write requests per day

- Assuming each entry is about 500 bytes

Non-Functional Requirements

We extract adjectives and descriptive phrases from the problem statement to identify quality constraints:

- "unique" alias → System must guarantee no collisions

- "millions of URLs" + "high traffic" → System must handle large scale

- "efficiently" + "near real-time" → System must respond quickly

- "persistent" → System must not lose data

- "handle high traffic" → System must remain operational under load

Each adjective becomes a non-functional requirement that constrains our design choices.

- High Availability: The service should ensure that all URLs are accessible 24/7, with minimal downtime, so users can reliably reach their destinations. (Derived from 'high traffic')

- Low Latency: URL redirections should occur almost instantly, ideally in under a few milliseconds, to provide a seamless experience for users. (Derived from 'near real-time' and 'efficiently')

- High Durability: Shortened URLs should be stored reliably so they persist over time, even across server failures, ensuring long-term accessibility. (Derived from 'persistent')

- Uniqueness: Each shortened URL must map to exactly one original URL across all users. (Derived from 'unique')

- Security: The service must prevent malicious links from being created and protect user data, implementing safeguards against spam, abuse, and unauthorized access to sensitive information.

Data Model

The data model is derived from extracting nouns in the problem statement:

- "URL" and "alias" → URLMapping entity with short_url and original_url fields

- "link usage" and "click counts" → Analytics entity with click_count field

- "persistent" requirement → created_at timestamp for durability tracking

Ownership is distributed across services to enable independent scaling. The URL Shortening Service owns URLMapping to ensure unique ID generation. The Analytics Service owns Analytics to handle high-volume write traffic without impacting redirection performance.

URLMapping

Stores the mapping between short URLs and original URLs. This is the core entity that enables the shortening and redirection operations.

Analytics

Tracks access metrics for each shortened URL. Supports the link tracking functional requirement.

URLMapping and Analytics have a one-to-one relationship. Each shortened URL has exactly one analytics record. The relationship is optional - URLs can exist without analytics if tracking is disabled.

API Endpoints

We derive API endpoints directly from the functional requirements (verbs identified in Step 0):

-

CREATE operation: "takes a long URL and generates a shorter alias" → POST /api/urls/shorten (accepts longUrl, returns shortUrl)

-

READ operation: "redirects users to the original URL" → GET /api/urls/{shortUrl} (accepts shortUrl, returns longUrl or 302 redirect)

-

UPDATE operation: "track link usage" → Handled internally via event-driven architecture (not exposed as public API endpoint)

Each endpoint maps to exactly one core operation, following RESTful conventions where HTTP methods indicate operation type.

/api/urls/shortenShorten a given long URL and return the shortened URL.

/api/urls/{shortUrl}Redirect to the original long URL using the shortened URL.

High Level Design

1. URL Shortening

Users should be able to input a long URL and receive a unique, shortened alias. The shortened URL should use a compact format with English letters and digits to save space and ensure uniqueness.

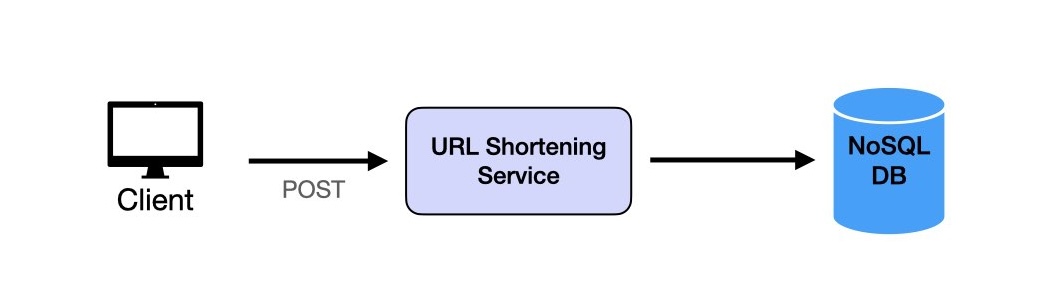

The design for URL shortening follows a basic two-tier architecture that processes requests quickly and scales to handle high volumes:

1. Client: The frontend application sends HTTP POST requests containing long URLs to the URL Shortening service.

2. URL Shortening Service: The backend receives requests and is responsible for creating and returning shortened URLs. It performs these key functions:

- Generates a unique, short alias by encoding the URL or using hashing techniques to ensure uniqueness.

- Stores the mapping of long URLs to short aliases in the database.

- Manages errors and ensures each short URL is unique across all users.

3. Database: A highly available database (e.g., DynamoDB or Cassandra) is used to persist mappings between long URLs and short aliases.

This design supports efficient and quick URL shortening with minimal data storage requirements per URL entry.

2. URL Redirection

When users access a shortened URL, the service should redirect them seamlessly to the original URL with minimal delay.

The URL redirection service ensures that users accessing a shortened URL are quickly redirected to the original URL with minimal delay. This design focuses on high read throughput and low latency, as the read traffic will be significantly higher than URL creation.

1. API Gateway: As we now have two request types, we need an API Gateway. This acts as the entry point for all incoming requests, routing POST requests to the URL Shortening Service and GET requests to the URL Redirection Handler.

2. URL Redirection Request Handler: Accepts GET requests with the shortened URL, queries the cache for the original URL, and responds with a 302 Found status and the original URL in the Location header to facilitate seamless redirection.

3. Caching Layer: To reduce latency and offload read requests from the database, we implement a read-through caching layer (e.g., Redis with cache libraries) that stores frequently accessed URL mappings in memory. When a URL is not found in the cache, the cache itself automatically retrieves it from the database and stores it for future requests, making the process transparent to the Request Handler.

4. Database: The database stores all URL mappings. The cache layer automatically queries the database when needed, without requiring the Request Handler to manage cache misses directly.

This setup ensures efficient and reliable URL redirection at scale by combining the API Gateway, Request Handler, Caching Layer, and Database.

3. Link Analytics

The system should be able to track the number of times each shortened URL is accessed to provide insights into link usage.

To track the number of accesses for each shortened URL, we introduce an Analytics Service that counts and stores access events in real time. This setup provides useful insights into link usage patterns and is designed to scale for high traffic.

1. API Gateway: Routes GET requests to both the URL Redirection Handler (for redirection) and the Analytics Service (for tracking access).

2. Analytics Service: Tracks each URL access by incrementing a counter associated with the short URL. This service logs access events and can be optimized by using a lightweight in-memory counter before periodically updating the database.

3. In-Memory Database: For high-speed access counting, we use an in-memory data store like Redis to cache the counters for each short URL. This enables real-time tracking and reduces the load on the main database.

4. Database: Periodically, the Analytics Service flushes the in-memory counters to the main database to ensure persistent storage of access counts.

This architecture enables efficient, real-time analytics collection, combining the speed of in-memory storage with the durability of a database.

Deep Dive Questions

What are the two properties we need for the IDs?

The two properties we need for the IDs are:

- Global Uniqueness: It has to be globally unique across our system. We obviously do not want two long URLs to map the same the short URL.

- Shortness: It has to be "short". This is a relative concept. The URL shorteners used in production are around 5-8 characters long. For example, https://shorturl.at/xLMPr, https://t.ly/ecgGp and https://tinyurl.com/e9enh3uz.

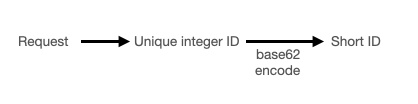

The basic idea behind URL generation involves creating a unique integer ID for each URL, followed by encoding that ID into a shorter, human-readable format. Let's discuss each one in detail.

How can we generate unique IDs for each URL?

There are several options for generating unique integer IDs:

Note that when we say "integer" in programming and computer science, we typically mean a whole number that can be represented in different number systems. For example, 123456 in decimal is 123456 in decimal, 123456 in hexadecimal is 0x1e240, and 123456 in binary is 0b1111000100100000.

How can we encode the unique IDs into short, user-friendly URLs?

After generating a unique integer ID for each URL, we need to encode it into a shorter, readable string to create a user-friendly shortened URL. The encoding method must balance shortness with usability, avoiding special characters that might be confusing or hard to type.

Several encoding options were considered:

How can we scale the system to handle high traffic?

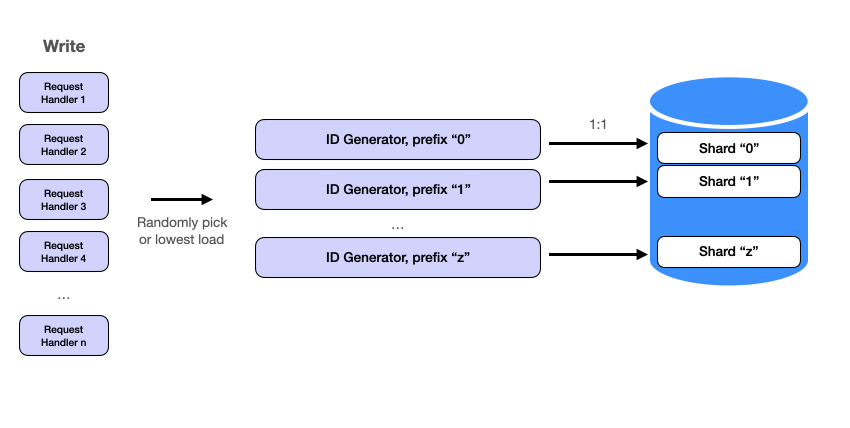

To support high traffic and ensure scalability, we implement a sharding strategy that distributes data and load across multiple machines. Sharding allows us to scale horizontally, so as traffic increases, we can add more machines without reconfiguring the entire system.

Scaling with Sharding

With ID generation in place, the next step is to scale the system. Request handlers can be easily scaled as they function as independent HTTP servers. However, scaling the ID generator requires a bit more consideration.

Machine ID (Prefix) as Shard Key

To horizontally scale the system, we need to shard the service. We already have a solution from the previous section: using 1 character for the machine ID. This "prefix" serves as the shard key for our ID Generator service. By sharding the database and ID Generator using the same shard key, each machine corresponds to exactly one database shard. This is a common design pattern. The approach ensures that write paths are completely independent and concurrent so we can scale the entire system by adding more servers without affecting existing ones.

The primary benefits of this approach:

Scalability: Adding more machines to the system is straightforward. Each new machine is assigned a unique prefix, allowing it to generate IDs and write to its own shard without impacting the existing setup. This allows the system to handle increased load seamlessly.

Concurrency: Independent write paths mean that multiple machines can perform write operations simultaneously without conflicting with each other. This parallelism enhances the system's overall throughput and efficiency.

Additionally, we also get some nice side benefits.

Isolation: Each machine and its corresponding database shard operate independently, minimizing the risk of system-wide failures. If one machine or shard encounters an issue, it does not affect the others, ensuring higher system reliability.

Simplicity in Data Management: With each machine handling a distinct shard, data management becomes simpler. Maintenance tasks such as backups, indexing, and scaling can be performed on individual shards without disrupting the entire system.

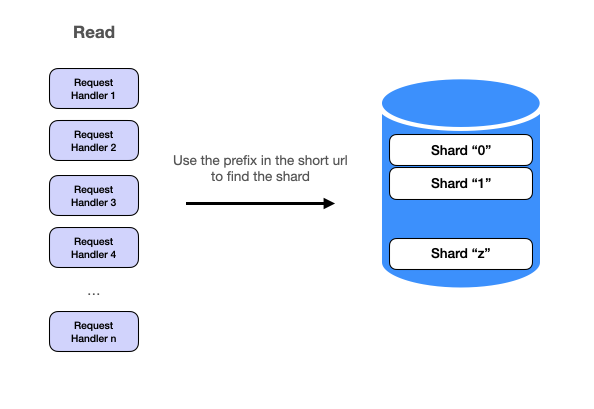

For the read request, if there is a cache miss, we can use the prefix in the short url to find the proper database shard to find the data. For example, if the short url is a82c7w, the request handler would go to shard a to find the long url. We could go even further to shard the cache using the same shard key if it becomes necessary

Staff-Level Discussion Topics

StaffThe following topics contain open-ended architectural questions without prescriptive solutions. They are designed for staff+ conversations where you demonstrate systems thinking, trade-off analysis, and strategic decision-making.

Level Expectations

The following table summarizes what interviewers typically expect at each level when discussing URL shortener design. Use this as a guide for calibrating depth of discussion.

| Dimension | Mid-Level (L4) | Senior (L5) | Staff (L6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID Generation | Explain uniqueness and shortness requirements; suggest one valid approach | Compare hash vs UUID vs Snowflake vs Machine ID approaches with tradeoffs | Design ID coordination across regions; handle clock skew and machine failures |

| Encoding Strategy | Explain Base62 encoding and calculate ID space (62^6 ≈ 56B) | Discuss Base16/62/64 tradeoffs; explain why special characters matter in URLs | Consider encoding implications for analytics, debugging, and URL patterns |

| Scaling Strategy | Understand sharding concept and why it enables horizontal scaling | Design shard key strategy; explain write path independence and read routing | Handle shard rebalancing, hot shards, and consistent hashing alternatives |

| Caching & Performance | Include cache layer in design; explain read-through pattern | Calculate cache hit ratios; design cache invalidation strategy | Design multi-tier caching; handle cache stampede and thundering herd |