Introduction

A developer debugging a production issue copies 200 lines of error logs and pastes them into a text box. They click "Create Paste" and receive a short URL like pb.example/a7x3k. They post this link in a GitHub issue asking for help. Over the next week, dozens of developers investigating the same bug click that link.

This simple interaction hides interesting challenges: How do we generate millions of unique short URLs without collisions? Where do we store text that ranges from 10 bytes to 1 megabyte? How do we serve content fast when reads vastly outnumber writes?

Functional Requirements

Pastebin has two core operations: storing text and retrieving it.

The write path generates unique IDs and persists data. At 12 writes/sec, this is straightforward—the interesting decision is where to store the actual text content.

The read path serves content fast. With a 100:1 read-to-write ratio (~1,200 reads/sec), CDN caching isn't optional—it's essential.

We decompose into:

-

Store text - Handle uploads, generate IDs, persist to storage

-

Retrieve text - Serve content with low latency using CDN

-

Users upload text content. The system generates a unique short URL and persists the text. The URL is returned immediately for sharing.

-

Users access a paste via its unique URL. The system retrieves and returns the text content with low latency.

Scale Requirements

- 1M Daily Active Users

- Read:write ratio = 100:1 (pastes shared on forums, GitHub issues, and documentation get many views)

- Data retention for 3 months

- 1 write operation per user per day

- Average paste size 10KB (max 1MB)

Non-Functional Requirements

- Low latency: Paste retrieval under 100ms (users expect instant page loads)

- High durability: Text must not be lost once stored (developers paste important code)

- High availability: 99.9% uptime (43 minutes downtime per month maximum)

- Keep URLs unlisted: Prevent scraping of all pastes (sensitive code snippets, config files). Important assumption: once shared, assume the whole world can access it—others can spread the URL freely. Deletion removes access but cannot prevent prior cloning. The entire design is based on this assumption.

API Endpoints

/pasteCreate a new paste. Returns a short URL and delete token immediately. Size limit 1MB to prevent abuse.

/{id}Retrieve paste content. Returns 404 if expired or not found.

/{id}Delete a paste early. Requires the delete_token returned at creation.

High Level Design

1. Store Text

Users upload text content. The system generates a unique short URL and persists the text. The URL is returned immediately for sharing.

A developer pastes 50 lines of error logs and clicks "Create." Within 200ms, they have a URL to share. Let's work through how to build this.

The First Decision: Where Should We Store the Text?

The simplest approach stores everything in one database table:

CREATE TABLE pastes (

id VARCHAR(8) PRIMARY KEY,

content TEXT,

created_at TIMESTAMP

);But let's think through what happens at scale. Text content varies wildly—from 10 bytes to 1 megabyte. With 1M pastes per day at 10KB average, we're storing 900GB over 3 months. Putting all that in a relational database creates problems:

- Table bloat: Large TEXT columns fragment across pages, slowing queries

- Backup pain: Database dumps include all content—900GB takes hours to backup and restore

- Cost: Database storage costs significantly more per GB than object storage

This points us toward separating metadata from content. We're going to choose a hybrid approach: database for metadata, object storage for content. Here's why: the database stays fast for queries we actually need (checking expiry, analytics), while object storage handles the bulk content at a fraction of the cost.

High-Level Architecture

The system separates concerns:

- Database holds metadata: ID, creation time, expiry time, content size (fixed-size rows, fast queries)

- Object storage holds text content: keyed by paste ID (cheap, durable, unlimited scale)

- CDN serves content to users: sits in front of object storage as origin, caches at edge locations worldwide

- Cache holds metadata for fast lookups: "does this paste exist?" checks without hitting the database

The Write Path

Now that we've decided where to store data, let's trace through what happens when a user creates a paste.

- Request arrives at the load balancer and routes to an application server

- ID generation creates a unique short identifier (we'll dig into this next)

- Object storage receives the text content at path

/{id} - Database stores metadata:

INSERT INTO pastes (id, created_at, expires_at, size_bytes) - Response returns the short URL to the user

The write path takes a moment—object storage writes aren't instant. This is acceptable since users don't expect immediate response when uploading content.

The Second Decision: How Do We Generate Unique IDs?

So far we've covered where to store data and how the write path flows. But there's a critical piece we glossed over: generating the short ID like a7x3k. This ID must be unique across all 90M pastes. Let's think through the options. (For a deeper dive, see Unique ID Generators.)

Our Choice: Random Generation

We're going to choose random generation with collision check. The collision check relies on the database primary key constraint—just attempt the insert and catch the duplicate key error. No separate lookup query needed. Collision probability is tiny (0.00004%), so retries are rare. The implementation is simple, and we get security against enumeration. Pre-generated pools and Bloom filters add operational complexity that isn't justified at this scale.

Data Schema

CREATE TABLE pastes (

id VARCHAR(8) PRIMARY KEY, -- "a7x3k"

created_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

expires_at TIMESTAMP, -- NULL means never expires

size_bytes INT NOT NULL -- for analytics, rate limiting

);

CREATE INDEX idx_expires ON pastes(expires_at); -- for cleanup jobThe actual text lives in object storage at path /{id} (matching the URL path). Notice the schema is tiny—just 4 columns. This keeps the database fast and backups quick.

2. Retrieve Text

Users access a paste via its unique URL. The system retrieves and returns the text content with low latency.

So far we've designed the write path: users upload text, we generate a unique ID, store content in object storage, and save metadata in the database. But there's a critical piece missing: how do users actually retrieve their pastes? A teammate clicks pb.example/a7x3k in a GitHub issue and expects the page to load instantly. Let's work through how to make that happen.

The Baseline: Read Without Caching

Let's trace through what happens without any optimization:

- Parse ID from URL:

a7x3k - Query database:

SELECT * FROM pastes WHERE id = 'a7x3k' - Check if expired (compare

expires_atwith current time) - Fetch content from object storage:

GET /a7x3k - Return content to user

Object storage requests add latency compared to serving from memory or edge cache. With our 100:1 read-to-write ratio and 1M DAU creating 1 paste/day, we have:

Reads/day = 1M pastes/day × 100 reads/paste = 100M reads/day

Read QPS = 100M ÷ 86,400 seconds ≈ 1,157 reads/sec

This baseline works, but it's inefficient. With a 100:1 read ratio, the same paste gets fetched from origin storage over and over—roughly 100 times on average. Every read pays the full round-trip to origin. And since pastes never change after creation, we're repeatedly fetching identical content.

This is exactly the pattern caching solves. Edge caches serve content from locations closer to users, absorb most of the read traffic, and work perfectly with immutable data like pastes.

The Key Decision: How Do We Speed Up Reads?

We need to serve content faster than fetching from object storage on every request. Let's think through the options.

Our Choice: CDN for Content

We're going to choose CDN caching for content. Here's why: CDN is purpose-built for serving static blobs. Paste content is immutable, making it ideal for edge caching. Object storage + CDN is a common, battle-tested pattern. Memory-based caches should store small, frequently-accessed data (metadata, sessions)—not multi-KB blobs.

For metadata, we add an in-memory cache for fast "does this paste exist?" lookups. At ~1,200 reads/sec the database could handle this directly, but cache reduces latency and protects the database from read spikes.

Read Path With CDN

We've decided to use CDN for content. But how does the client actually reach the CDN? The write path returns a short URL like pb.example/a7x3k—where does that request go?

Our Choice: CDN in Front

We're going to choose CDN in front of the domain. Here's why: single domain gives users a clean experience, no extra latency from redirects, and we already rely on the cleanup job for expiry anyway.

You configure the CDN with multiple origins and path-based routing rules:

- Origin A: Object storage (paste content)

- Origin B: App server / load balancer (API + writes)

Routing rules:

/api/*→ Origin B (app server)/*→ Origin A (object storage)

The main domain points to CDN, and the CDN forwards to the right origin based on the request path. Most CDN providers support this pattern.

- Client requests

pb.example/a7x3k - CDN hit: Edge cache returns content immediately

- CDN miss: CDN fetches from object storage origin, caches at edge, returns to client

Most reads hit the CDN edge cache. Cache misses fetch from origin and populate the CDN for subsequent requests.

CDN Caching Behavior

CDNs use a pull-through pattern: on the first request for a paste, the CDN fetches from object storage (origin), caches the response at the edge, and serves subsequent requests from cache. This is ideal for pastebin because most pastes are accessed a few times shortly after creation, then forgotten. The CDN naturally caches "hot" content and lets "cold" content fall out.

Handling Expired Pastes

So far we've covered reading active pastes. But what happens when a user clicks a link to a paste that expired yesterday?

With CDN-only reads, we can't check expires_at per-request—there's no app server in the path. Instead, we rely on the background cleanup job to delete expired content:

- Cleanup job runs nightly, finds pastes where

expires_at < now() - Deletes from database and object storage (we pay for stored objects, so cleanup saves cost)

- Invalidates CDN cache for deleted pastes

After cleanup runs, requests for expired pastes return 404 from object storage (object doesn't exist). Before cleanup runs, expired content may still be served—this brief window is acceptable for most use cases.

You might be thinking: "Can't we check expiry at the edge?" Yes, but each approach adds per-request overhead:

- Edge functions: Every read now needs a metadata lookup to check

expires_at. The edge must query the database or a cache on each request, adding latency and failure modes. - Signed URLs: Embed expiry in the URL itself (e.g.,

pb.example/a7x3k?expires=1705410000&sig=abc123). Requires key management for signing, and you can't extend expiry after the URL is shared.

The cleanup job, by contrast, already exists for storage cost reasons. Adding CDN invalidation is just one more step in a job we're already running. For pastebin, where users rarely access pastes right at the expiry boundary, this tradeoff makes sense.

-- Cleanup job runs at 3am

DELETE FROM pastes WHERE expires_at < NOW() - INTERVAL '1 day';The 1-day buffer handles timezone edge cases and gives users a grace period. The cleanup job can also delete corresponding objects in batch—much more efficient than one-at-a-time deletion.

Deep Dive Questions

How do we handle traffic spikes when many users create pastes simultaneously?

So far we've designed for steady-state traffic. From our scale requirements (1M DAU, 1 paste/user/day, 100:1 read:write ratio):

Write QPS = 1M pastes/day ÷ 86,400 seconds ≈ 12 writes/sec

Read QPS = 100M reads/day ÷ 86,400 seconds ≈ 1,157 reads/sec

But real traffic isn't steady. What happens when AWS has a major outage and thousands of developers simultaneously paste error logs to share with teammates? Write QPS jumps from 12 to 1,200—a 100x spike.

Scaling the Application Tier

The good news: application servers are stateless. They don't store paste data locally—everything goes to object storage and the database. This means we can scale them horizontally without coordination.

Behind the load balancer, an auto-scaling group monitors CPU and request count. When traffic spikes, it launches additional instances. Cloud providers can spin up 10x capacity in minutes. The load balancer automatically routes traffic to new instances.

This handles the request processing side. But here's the catch: all those servers still write to the same database.

Understanding the Bottleneck

Let's trace through what breaks. Your database has a connection pool of 100 connections. With 1,200 requests/second and each write taking 50ms, you need 60 concurrent connections just to keep up. The pool exhausts. Requests queue up. Timeouts cascade. Users see "Service Unavailable."

The database is the bottleneck. It can't handle 100x load instantly. Let's think through how to absorb spikes without 100x provisioning.

The First Instinct: Scale Up

You might be thinking: "Can't we just scale the database horizontally too?" Yes, but database sharding is complex—partitioning by paste ID, handling cross-shard queries, managing shard routing. For 12 writes/sec baseline, that's massive over-engineering.

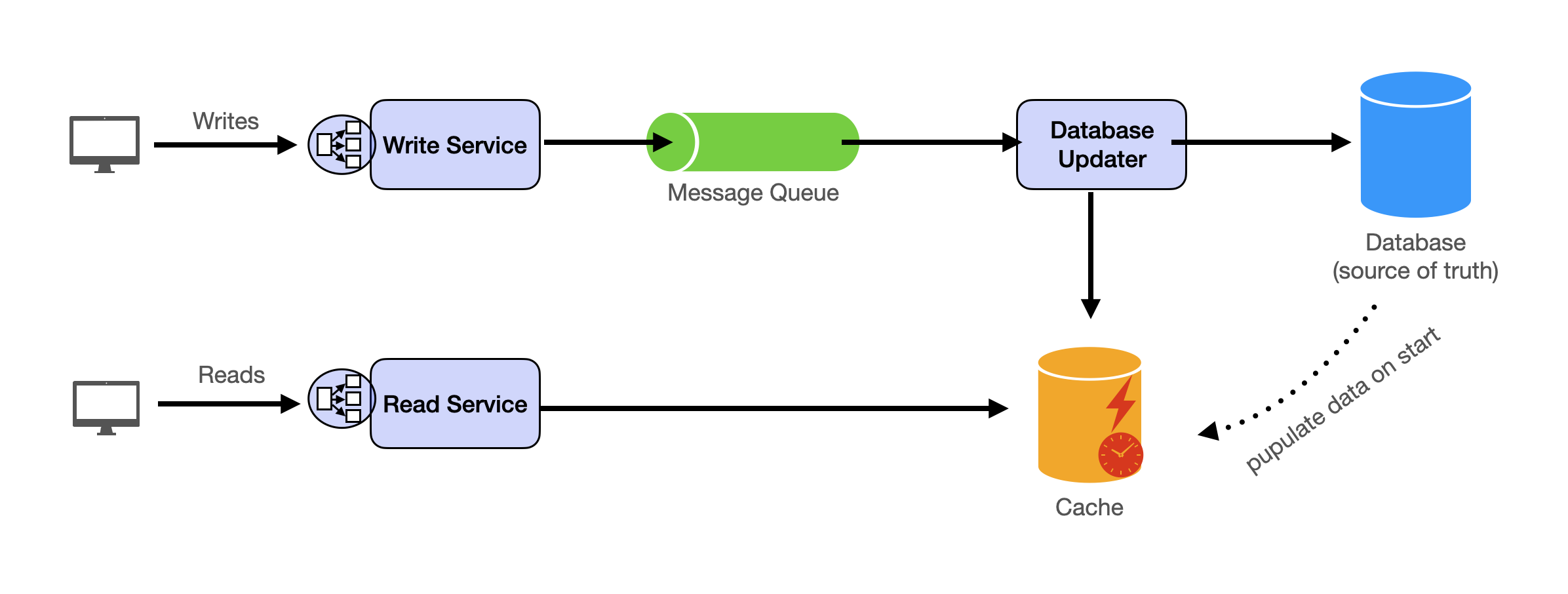

Decouple Request Handling from Persistence

Here's the mental shift: users don't need their paste persisted synchronously. They need a URL immediately. The actual storage can happen seconds later. This is where message queues shine.

Our Recommendation

We're going to choose message queue buffering with rate limiting as a safety valve. Here's why:

- Normal traffic (12 writes/sec): writes go directly to storage, low latency

- High traffic (100x spike): writes queue up, drain over time, users still get URLs immediately

- Extreme traffic (queue depth exceeds threshold): rate limiting kicks in, returns 429, protects the queue from growing unbounded

The slight delay from queueing is invisible to users. The experience stays smooth even during major incidents. And we don't pay for 100x capacity that sits idle 99.9% of the time.

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.