Introduction

There is a question bank that stores thousands of programming questions. For each question, users can write, compile and submit code against test cases and get immediate feedback on correctness. User submitted code needs to be persisted for review and tracking.

Every week, there is a contest where thousands of people compete concurrently to solve questions as quickly as possible. Users are ranked based on their accuracy and speed. The leaderboard provides real-time updates during the 2-hour contest, showing rankings as participants submit solutions. After the contest ends, the leaderboard becomes a frozen historical view preserving the final standings.

Functional Requirements

We extract verbs from the problem statement to identify core operations:

- "view" and implicit "browse" (question bank) → READ operation (View Problems)

- "write, compile and submit code" + "get immediate feedback" → CREATE/READ operations (Submit Solution)

- "compete" + "ranked" + "real-time updates" → UPDATE/READ operations (Coding Contest with real-time leaderboard)

Each verb maps to a functional requirement that defines what the system must do.

-

Users should be able to view problem descriptions, examples, constraints, and browse a list of problems.

-

Users should be able to solve coding questions by submitting their solution code and running it against built-in test cases to get results.

-

User can participate in coding contest. The contest is a timed event with a fixed duration of 2 hours consisting of four questions. The score is calculated based on the number of questions solved and the time taken to solve them. The results will be displayed in real time. The leaderboard will show the top 50 users with their usernames and scores.

Scale Requirements

- Supporting 10k users participating contests concurrently

- There is at most one contest a day

- Each contest lasts 2 hours

- Each user submits solutions 20 times on average

- Each submission executes 20 test cases on average

- User submitted code have a retention policy of 1 month after which they will be deleted.

- Assuming that the storage space required for the solution of each coding question is 10KB.

- Assuming that the read:write ratio is 2:1.

Non-Functional Requirements

We extract adjectives and descriptive phrases from the problem statement to identify quality constraints:

- "thousands of people compete concurrently" + "10k users participating contests concurrently" → System must handle high concurrency and scale

- "immediate feedback" + "real-time updates" → System must have low latency for code execution results and leaderboard updates

- "persisted" (user submitted code) → System must ensure data durability and not lose submissions

- Implicit: executing untrusted user code → System must provide security and isolation to prevent malicious code from affecting the server

Each adjective and quality descriptor becomes a non-functional requirement that constrains our design choices.

- High availability: the website should be accessible 24/7

- High scalability: the website should be able to handle 10k users submitting code concurrently

- Low latency: during a contest, the leaderboard should be updated in real time

- Security: user code cannot break server

API Endpoints

We derive API endpoints directly from the functional requirements (verbs identified below):

-

READ operations: implicit "view" and "browse" for question bank → GET /problems?start={start}&end={end} (list problems with pagination) → GET /problems/:problem_id (get specific problem details)

-

CREATE operation: "write, compile and submit code" → POST /problems/:problem_id/submission (submit solution code for evaluation)

-

READ operations: "get immediate feedback" and "view leaderboard" → GET /submissions/:submission_id/status (poll for submission results) → GET /contests/:contest_id/leaderboard (fetch contest rankings)

Each endpoint maps to exactly one core operation, following RESTful conventions where HTTP methods indicate operation type.

/problems?start={start}&end={end}Get problems in a range. If start and end are not provided, get all problems with default page size.

/problems/:problem_idGet problem details, including description, constraints, examples, and starter code.

/problems/:problem_id/submissionSubmit code for a problem and get results.

/contests/:contest_id/leaderboardGet leaderboard for a contest.

High Level Design

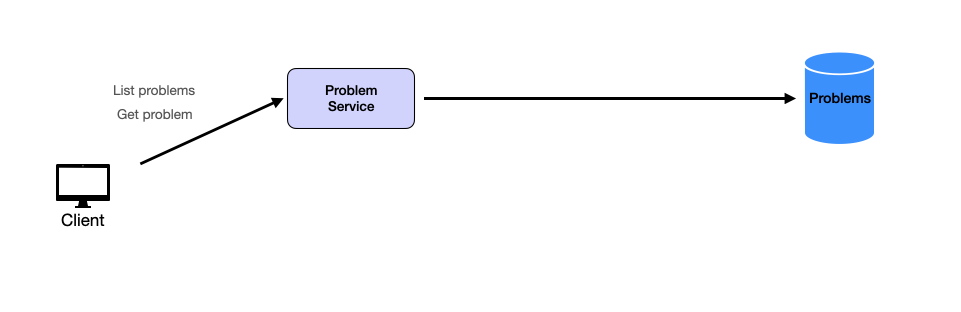

1. View Problems

Users should be able to view problem descriptions, examples, constraints, and browse a list of problems.

Let's start with the simplest requirement first. Viewing problems is straightforward and follows a standard three-tier architecture:

- Client: Frontend application sending HTTP GET requests

- Problems Service: Backend service with endpoints:

GET /problems?start={start}&end={end}: List problemsGET /problems/:problem_id: Get specific problem details

- Database: Stores problem data (id, title, description, difficulty, examples, constraints)

This simple setup efficiently handles problem viewing requests while maintaining separation of concerns. Now let's tackle the more interesting challenge: executing user code safely at scale.

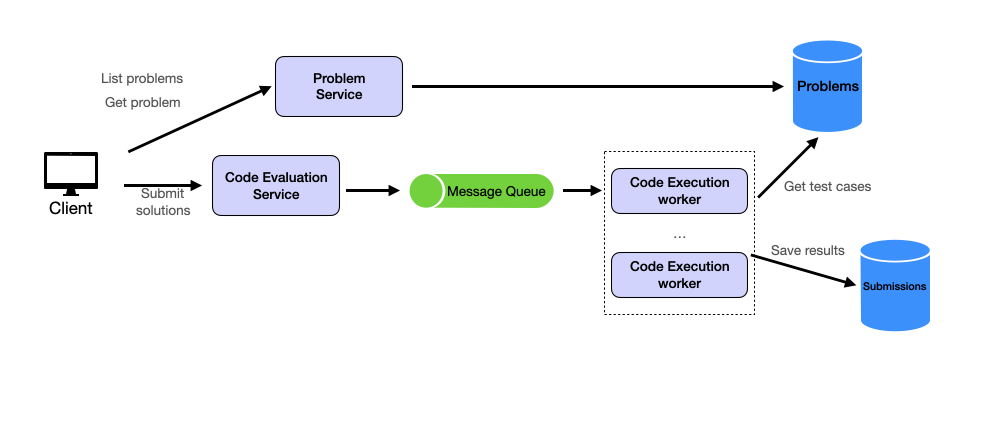

2. Submit Solution

Users should be able to solve coding questions by submitting their solution code and running it against built-in test cases to get results.

A user clicks "Submit" on their solution. The system must execute untrusted code against test cases and return results. But here's the constraint: 10,000 users submit during contests, each averaging 20 submissions. That's 200,000 code executions in 2 hours. Each execution takes CPU and memory to compile, run, and validate against test cases.

If we handle this in a single monolithic service, what happens when someone submits malicious code that crashes the process? Or when execution takes 10 seconds and blocks other users? We need separation. The service that receives submissions shouldn't be the same process running untrusted code.

This leads us to three components: a Problems Service for viewing problems, a Code Evaluation Service for receiving submissions, and Code Execution Workers for running the actual code. The Problems Service has steady traffic all day—users browse problems continuously. The Code Evaluation Service sees spikes during contest start and end. And the workers need to scale independently based on queue depth. Different traffic patterns, different scaling needs, different blast radius concerns.

But receiving 200,000 submissions in 2 hours creates another problem: what if submissions arrive faster than workers can execute them? At peak, 5,000 submissions might arrive in the first minute. We can't drop them, and we can't make users wait. This requires a buffer—a Message Queue that absorbs the spike and lets workers pull submissions at their own pace.

The flow: Code Evaluation Service validates the submission and pushes a message (user ID, problem ID, code) to the queue. This happens in milliseconds—the service doesn't wait for execution. The user gets a submission ID immediately.

Code Execution Workers pull messages from the queue. Each worker fetches test cases from the Problems database, executes the code, and records results. But where does the code actually run? We're executing untrusted code—a user could submit an infinite loop, a fork bomb, or code that tries to read our database credentials. The execution environment must provide isolation.

Code Execution Options

API Server

Direct execution on the API server

How it works:

The user-submitted code is directly executed on the same server that hosts the API. The code is typically saved as a file on the server's filesystem and then run using the appropriate interpreter or compiler.

Pros:

- Simple to implement

- Low latency as there's no additional layer between the API and code execution

Cons:

- Severe security risks: Malicious code can potentially access or modify server data

- Poor isolation: A bug in user code could crash the entire server

- Resource management issues: One user's code could consume all server resources

Conclusion:

Not suitable for running user-submitted code. The security and stability risks far outweigh the simplicity benefits.

Serverless functions scale automatically, but they have a problem: cold starts. The first invocation can take 500ms-2s while the function container initializes. During a contest with 5,000 submissions in the first minute, most would hit cold starts. Containers let us pre-scale—we spin up 100 containers 5 minutes before the contest starts, avoiding cold-start latency entirely. We know the schedule; we don't need auto-scaling's flexibility. Containers also give us tighter control over resource limits (CPU, memory, network) and avoid vendor lock-in.

Each submission runs in a fresh container with strict resource limits. After execution completes, results (pass/fail, execution time, memory usage) are saved to the Submissions table and the container terminates.

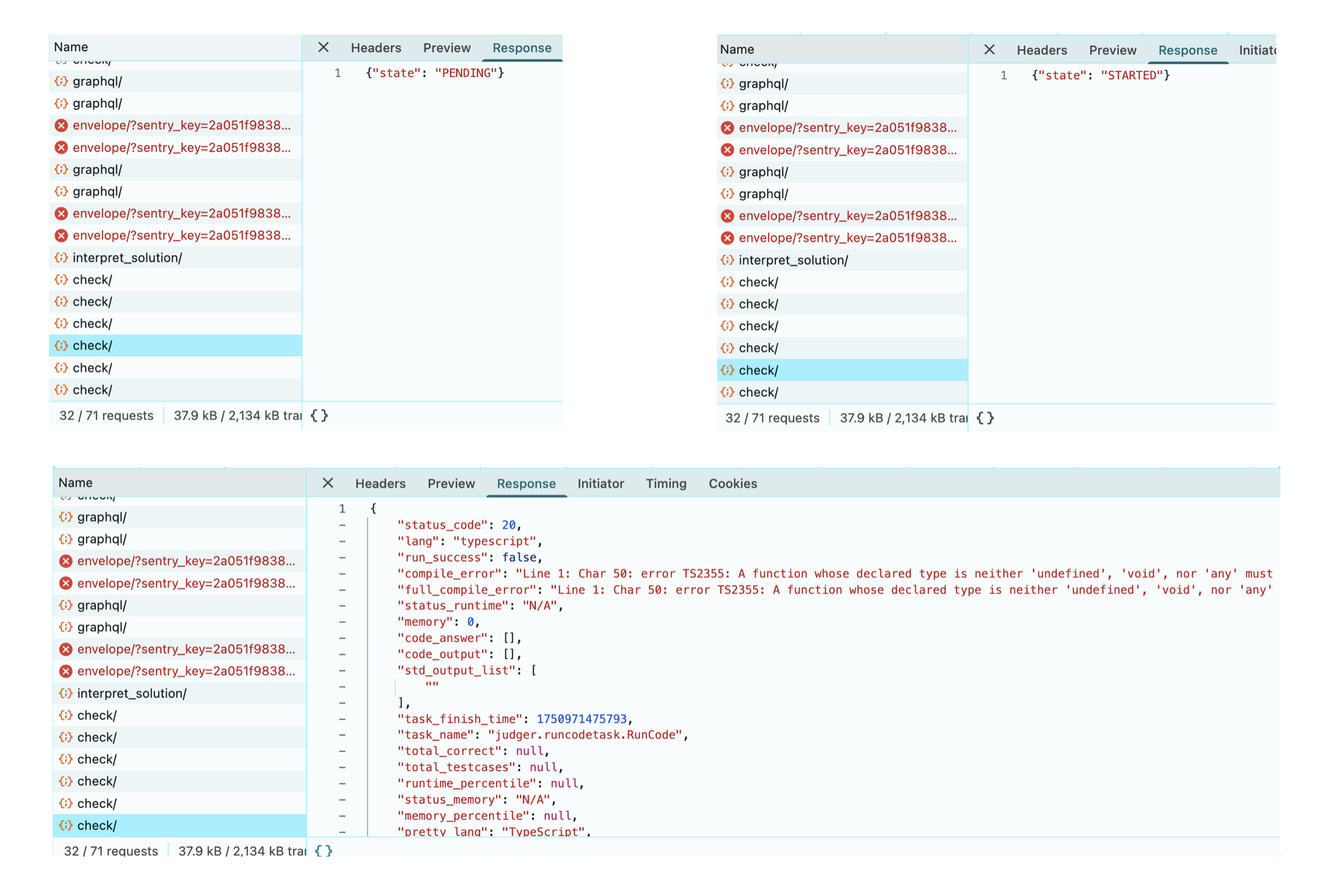

So far we've covered how to receive submissions, queue them, and execute them securely in containers. But there's one piece missing: how does the user actually get their results back? Code execution can take several seconds, so we can't have the API call just wait. We need an async approach.

Async Result Retrieval

The user submitted code. Execution takes 3 seconds. Do we keep the HTTP connection open for 3 seconds? During a contest with 10,000 concurrent users, that's 10,000 open connections waiting. If execution takes 10 seconds, the connection might timeout. We need async communication.

The solution: return a submission ID immediately, then let the client check back for results.

- Immediate response: Code Evaluation Service returns

{"submission_id": "abc123", "status": "pending"}in under 100ms - Polling: Client polls

GET /submissions/abc123/statusevery 1-2 seconds - Result delivery: When execution completes, the endpoint returns

{"status": "success", "passed": 8, "failed": 2, "time": 45ms}

This is how LeetCode works in production—you can see it in Chrome DevTools:

But why polling instead of WebSockets or Server-Sent Events?

WebSockets maintain bidirectional connections. During a contest, 10,000 concurrent WebSocket connections create memory pressure on the server—each connection holds buffers and state. We only need one-way communication (server → client) for status updates. The bidirectional capability adds complexity without benefit.

Server-Sent Events (SSE) are one-way but still require long-lived connections. With 10,000 concurrent users, that's 10,000 open HTTP connections the server must maintain.

Polling is stateless. The server handles a request, sends a response, and closes the connection. No memory held between requests. The "cost" of polling—1 request every 1-2 seconds per active submission—is negligible compared to maintaining 10,000 persistent connections. LeetCode proves this works at scale.

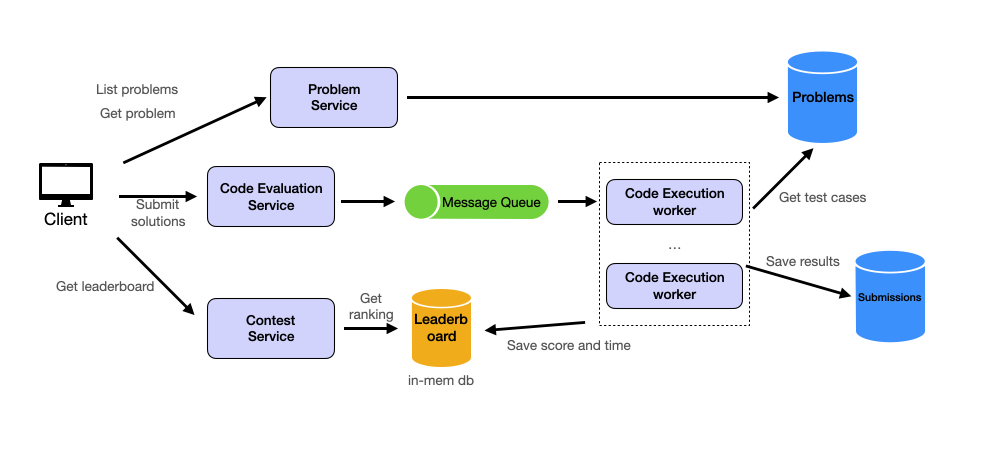

3. Coding Contest

User can participate in coding contest. The contest is a timed event with a fixed duration of 2 hours consisting of four questions. The score is calculated based on the number of questions solved and the time taken to solve them. The results will be displayed in real time. The leaderboard will show the top 50 users with their usernames and scores.

A contest is four problems with a 2-hour time window. The submission infrastructure already works—users submit code, it gets executed, results come back. So what's new?

The leaderboard. A user solves a hard problem at minute 45. They refresh the page: rank 47. Thirty seconds later, they refresh again: rank 52. Five users just submitted faster solutions. During the first 10 minutes of a contest, rankings change every few seconds as 10,000 developers compete.

This creates a data problem. Every submission that passes test cases updates that user's score. Their rank might change. Everyone below them shifts down one position. At peak, that's hundreds of score updates per second, each potentially reshuffling thousands of ranks. We need fast writes (update scores) and fast reads (query top 50).

A SQL database would struggle. The query SELECT * FROM leaderboard ORDER BY score DESC LIMIT 50 scans and sorts the entire leaderboard on every request. With scores changing hundreds of times per second, the ORDER BY never gets to use a stable index—it's recalculating constantly. We need a data structure that maintains sorted order automatically.

This points to an in-memory data structure like Redis sorted sets. When you insert a score, Redis maintains order using a skip list internally—no separate sort step needed. Querying top 50 is O(log n + 50), not O(n log n). Updates happen in O(log n). This matches our access pattern: frequent writes, frequent sorted queries. We will discuss more on this in the deep dive section.

We'll use a Contest Service to orchestrate this. When Code Evaluation Service finishes grading a submission, it notifies Contest Service. Contest Service calculates the new score (combining points and time penalties) and updates Redis. The leaderboard API queries Redis sorted set for top 50.

Deep Dive Questions

How does the Code Evaluation Service decides if a submission is correct?

This is one of those questions that tests whether you can move beyond box-drawing into actual implementation. Let's break this down with a concrete example.

The Code Evaluation Service decides if a submission is correct by comparing the output of the code with the expected output. The important requirement: we need a language-agnostic way to store test cases so we don't have to maintain separate test cases for Python, Java, C++, etc.

Here's how this works with a simple example:

Requirement:

- Problem: Add two numbers

- Input: 2, 3

- Expected Output: 5

- Time Limit: 1 second

User submitted code:

def add(a, b):

return a + bTest case files:

test_case_1.in

2, 3test_case_1_expected_output.out

5test_case_1.out

5The Code Evaluation Service will run the code with the input and get an output file test_case_1.out.

It will then compare test_case_1.out with test_case_1_expected_output.out. If they are the same, the submission is marked as correct.

Otherwise, it's marked as incorrect.

If the code fails to execute, the submission is marked as failed. If the code execution time exceeds the time limit, the submission is marked as timeout.

- The test cases files such as

test_case_1.inandtest_case_1_expected_output.outare stored in the database.

How to ensure security and isolation in code execution?

Running the code in a sandboxed environment like a container already provides a measure of security and isolation.

We can further enhance security by limiting the resources that each code execution can use, such as CPU, memory, and disk I/O.

We can also use technologies like seccomp to further limit the system calls that the code can make.

To be specific, to prevent malicious code from affecting other users' submissions, we can use the following techniques:

- Resource Limitation: Limit the resources that each code execution can use, such as CPU, memory, and disk I/O.

- Time Limitation: Limit the execution time of each code execution.

- System Call Limitation: Use technologies like

seccompto limit the system calls that the code can make. - User Isolation: Run each user's code in a separate container.

- Network Isolation: Limit the network access of each code execution.

- File System Isolation: Limit the file system access of each code execution.

Here's sample command while running docker run ...:

--cpus="0.5" --memory="512M" --cap-drop="ALL" --network="none" --read-onlyThis limits the code execution to use at most 0.5 CPU, 512 MB of memory, disables all capabilities, restricts network access, and makes the filesystem read-only.

How to implement a leaderboard that supports top N queries in real time?

This is one of the most common interview deep dives for contest/gaming systems, so let's break it down carefully. We have several options for implementing a real-time leaderboard. The key trade-off is between query speed, update speed, and storage cost.

Leaderboard Implementation Options

Redis Sorted Set

In-memory data structure store, using ZSET for leaderboard

How it works:

Uses a sorted set data structure to maintain scores. Each user is a member of the set, with their score as the sorting criteria.

Pros:

- Extremely fast read and write operations

- Built-in ranking and range queries

- Scalable and can handle high concurrency

Cons:

- Data is volatile (in-memory), requiring persistence strategies

- May require additional infrastructure setup

Conclusion:

Highly suitable for real-time leaderboards with frequent updates and queries.

Looking at these options, we're going to choose Redis Sorted Set. Here's why: the leaderboard data is temporary—only needed during and shortly after the contest—so in-memory storage makes sense. We don't need the durability guarantees of a traditional database. The built-in ZSET data structure is purpose-built for rankings, giving us O(log n) updates and O(n) top-N queries. This is exactly the performance profile we need.

Let's see how this works under the hood. Redis actually comes with a built-in leaderboard implementation using sorted sets (ZSET). Sorted sets combine unique elements (members) with a score, and they keep the elements ordered by the score automatically.

In Redis, this is implemented as ZSET. We use ZADD to add a user and its score, and use ZREVRANGE to get the top N users (highest scores first).

Leaderboard Example Here's a simple example:

ZADD leaderboard 100 user1

ZADD leaderboard 200 user2

ZADD leaderboard 300 user3

ZREVRANGE leaderboard 0 1 # returns the top 2 usersHow are contest scores calculated?

A natural follow-up question after discussing the leaderboard is how scores are calculated. A fair ranking system must answer: who solved harder problems, who solved them faster, and who made fewer failed submissions to discourage guessing. This leads us to a three-component score.

Points: The primary factor. Harder problems award more points. If User A solves 3 problems worth 500+1000+2000=3500 points and User B solves 2 problems worth 500+1000=1500 points, User A ranks higher regardless of time.

Time: The tie-breaker when points are equal. We track when you submit your last correct solution. Between two users with 1500 points, the one who finished at minute 30 beats the one who finished at minute 45.

Penalties: Wrong submissions add time. Each failed attempt typically adds 5 minutes. This discourages guessing.

Here's how these combine for a concrete user:

- Solves Problem A (500 points) at minute 15 after 1 wrong attempt

- Solves Problem B (1000 points) at minute 45 with no mistakes

- Total points: 1500

- Finish time: 45 minutes

- Penalty: 1 × 5 = 5 minutes

- Final time: 50 minutes

LeetCode uses this static scoring model. Codeforces adds time pressure by decaying problem values (a 500-point problem drops ~4 points per minute) and deducting 50 points per wrong submission.

When a submission completes evaluation, we update the user's score: if accepted and previously unsolved, add the problem points and update finish time to current contest time; if rejected, increment the wrong attempt counter.

How do we store composite scores (points + time) in Redis sorted sets?

We established that rankings depend on two factors: points (primary) and time (tie-breaker). Redis sorted sets only accept one numeric score per member. The challenge: pack both values into a single number that preserves the correct ranking order.

The constraint is strict. If User A has 5 problems solved in 120 seconds and User B has 5 problems in 90 seconds, User B must rank higher. If User C solves 6 problems in 500 seconds, they must beat both A and B despite taking longer. The single Redis score must encode this logic.

How to handle a large number of contestants submitting solutions at the same time?

This is where things get interesting. Think about what happens when a contest starts: 10,000 developers all click "submit" within the first few minutes. Then there's another spike at the end as people rush to finish. We've already built some resilience with the message queue, but let's think through whether that's enough.

The message queue helps, but here's the problem: if we have 5,000 submissions in the first minute and each takes 3 seconds to execute against 100 test cases, we'd need massive compute capacity sitting idle before the contest starts. Auto-scaling won't help—by the time new containers spin up, users are already frustrated by slow results.

Let's walk through a comprehensive strategy that combines several approaches:

-

Message Queue: Use a message queue to decouple the submission process from the execution process. This allows us to buffer submissions during peak times and process them as resources become available. We already have this from our earlier design.

-

Pre-scaling: Since auto-scaling may not be fast enough to handle sudden spikes, pre-scale the execution servers before the contest starts. This is especially important for the first and last 10 minutes of a contest when submission rates are typically highest.

-

Two-Phase Processing:

- Phase 1 (During Contest): Implement partial evaluation

- Run submissions against only about 10% of the test cases.

- Provide a partial standing for users, giving them immediate feedback.

- Phase 2 (Post-Contest): Complete full evaluation

- After the contest deadline, run the submissions on the remaining test cases.

- Determine the official results based on full evaluation.

- Phase 1 (During Contest): Implement partial evaluation

This two-phase approach:

- Reduces the load on the system during the contest by 90%.

- Allows for more accurate final results after full evaluation.

- Is similar to the approach used by platforms like Codeforces for large contests.

Now, you might think: "Won't users be upset if they don't get final results immediately?" Here's why this works: users care most about immediate feedback during the contest—they want to know if they're on the right track so they can debug and resubmit. Running 10% of test cases gives them that signal within seconds. The final validation with all test cases can happen after the deadline because at that point, they can't change their code anyway. This trade-off lets us handle 10x more concurrent submissions with the same infrastructure. Platforms like Codeforces have proven this works at scale—it's a battle-tested approach for large coding competitions.

Staff-Level Discussion Topics

StaffThe following topics contain open-ended architectural questions without prescriptive solutions. They are designed for staff+ conversations where you demonstrate systems thinking, trade-off analysis, and strategic decision-making.

Level Expectations

The following table summarizes what interviewers typically expect at each level when discussing online judge design. Use this as a guide for calibrating depth of discussion.

| Dimension | Mid-Level (L4) | Senior (L5) | Staff (L6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements & Estimation | List basic features (Submit, View, Leaderboard); minimal non-functional reqs | Define non-functional reqs (latency, security); calculate rough throughput | Detailed SLA discussion; failure mode handling; in-depth security risk analysis |

| Architecture | Client → API → DB; synchronous execution or simple async | Microservices (Problem, Eval, Contest); async workers with queues; decoupling | N/A |

| Code Execution | Basic isolation using containers; basic memory/time limits | Docker containers with resource limits (CPU/RAM) | cgroups internals; application kernels (gVisor) as middle ground between Docker and VMs |

| Leaderboard | Basic tie-breaking mechanism | Redis Sorted Sets (ZSET) | ZSET internals (skip lists); persistence and recovery strategies |

| Scalability & Trade-offs | Basic pre-scaling and caching | Pre-scaling; cost optimization; two-phase processing (partial vs full tests) | Explicit SLA definition; hill-climbing optimization strategies |