Introduction

A payment service finishes processing an order and needs to notify the shipping service, the analytics pipeline, and the email service. If the payment service calls each one directly, it becomes tightly coupled to all three. When the analytics service goes down for maintenance, the payment service either blocks waiting for a response or drops the event entirely.

A message queue sits between these services. The payment service publishes an "order completed" event once. The queue stores it durably and delivers it to every interested consumer independently. If analytics is down, the message waits in the queue until it recovers. No data lost, no coupling.

Every large-scale system uses message queues: order processing pipelines, real-time analytics, log aggregation, event-driven microservices. The challenge is building one that is durable (messages survive crashes), scalable (handles millions of messages per second), and flexible (supports both fan-out to multiple services and parallel processing within a single service).

Background

The question says "message queue," but that term covers two very different architectures. Before designing anything, we need to decide which one fits our requirements.

Two Families of Message Queues

Traditional AMQP-style queues (like RabbitMQ) work like a task list. A producer adds a message. One consumer picks it up, processes it, and the queue deletes it. Once consumed, the message is gone. This is ideal when each message represents a unit of work that should be processed exactly once by one worker—encoding a video, sending a notification.

Log-based queues work differently. Messages append to a persistent, ordered log. Consumers read from the log by tracking their position (called an offset). The message stays in the log regardless of how many consumers read it. Multiple consumer groups can each read the entire log independently. Messages persist for a configurable duration (days or weeks), not until consumption.

Why Log-Based

Our requirements specify three things that point to log-based:

-

Consumer groups — multiple services must consume the same topic independently. In AMQP, once a consumer processes a message, it's deleted. Other services never see it. Log-based queues keep the message, so analytics, billing, and shipping each read it at their own pace.

-

Ordering — messages within a partition must arrive in order. AMQP queues with competing consumers cannot guarantee ordering because any worker can pick up any message. Log-based queues assign each partition to one consumer within a group, preserving order.

-

Retention — messages persist for 7 days regardless of consumption. AMQP deletes messages after acknowledgment. Log-based queues retain messages by time or size, enabling replay and reprocessing.

This is a log-based message queue design. The rest of the article builds the system with this model.

(For background on the two queue families, see Message Queues and Log-Based Message Queues.)

Functional Requirements

The design builds progressively through four requirements:

FR1: Topic and Partition Management — Create the logical structure. Topics organize messages by category. Partitions within a topic enable parallel processing and ordered delivery.

FR2: Publish Messages — The write path. Producers send messages to a topic. The broker routes each message to a partition (via key hash or round-robin), appends it to the partition's log, and replicates to followers.

FR3: Consume Messages — The read path. Consumer groups subscribe to topics. Each partition within a topic is assigned to exactly one consumer in the group. Consumers track their position via offsets and pull messages sequentially.

FR4: Acknowledge and Retain — Lifecycle management. Consumers commit offsets to mark progress. Messages persist for the configured retention period regardless of consumption status. Expired messages are cleaned up by background processes.

-

Users can create named topics to categorize messages. Each topic is divided into one or more partitions. Partitions are the unit of parallelism, ordering, and storage.

-

Producers send messages to a specific topic. The broker appends each message to the appropriate partition's log and replicates it to follower nodes for durability.

-

Consumers read messages from topics. Consumer groups enable both fan-out (multiple services reading the same data) and parallel processing (multiple workers within a service splitting the load).

-

Consumers signal processing completion by committing offsets. Messages persist for a configurable retention period regardless of consumption status.

Scale Requirements

- 500,000 messages per second write throughput (think: medium-to-large event pipeline)

- 100,000 topics with varying partition counts

- Average message size: 1 KB (typical for structured events like JSON payloads)

- 7-day default retention (roughly 300 TB of raw message data at sustained peak)

- Thousands of consumer groups reading independently

Non-Functional Requirements

The scale requirements translate to these system qualities:

Durability

- Messages must not be lost once the broker acknowledges the write. Data must survive individual node failures through replication.

Throughput

- Handle 500K messages/second sustained write throughput across the cluster. This is roughly 500 MB/s of raw data at 1 KB per message.

Availability

- The system must remain operational when individual broker nodes fail. Partition leaders must failover to replicas without manual intervention.

Latency

- Publish latency under 10ms for the common case (write to leader + flush to page cache). End-to-end latency (publish to consumer delivery) under 100ms.

Delivery Guarantee

- At-least-once by default. The queue guarantees no message loss, but consumers may receive duplicates after failures. Exactly-once requires consumer cooperation (covered in deep dive).

Storage Efficiency

-

7-day retention at 500K msg/s × 1 KB = roughly 300 TB. Must use sequential I/O and compression to keep storage costs manageable.

-

Messages must not be lost once acknowledged by the broker (high durability via replication)

-

The system must handle 500K messages/second write throughput by distributing load across partitions

-

The system must remain operational when a broker node fails (automatic leader failover)

-

Support at-least-once delivery semantics by default

-

Messages must be stored on disk to handle backlogs larger than available memory

-

Publish latency under 10ms; end-to-end delivery latency under 100ms

High Level Design

1. Topic and Partition Management

Users can create named topics to categorize messages. Each topic is divided into one or more partitions. Partitions are the unit of parallelism, ordering, and storage.

Why Partitions

A topic could store all messages in a single log. But a single log on a single disk limits throughput to what one disk can handle. If the "Orders" topic receives 100,000 messages per second and a single disk handles roughly 10,000 sequential writes per second, one log cannot keep up.

Partitions solve this by splitting a topic's messages across multiple independent logs. Each partition is an append-only log stored on a different broker. With 10 partitions across 10 brokers, the "Orders" topic handles 100,000 messages per second—each broker handles 10,000.

Partition Assignment

When a producer sends a message, it needs to choose which partition receives it. Two strategies:

-

Key-based routing: The producer provides a partition key (like

user_idororder_id). The broker hashes the key:partition = hash(key) % num_partitions. All messages with the same key go to the same partition, which guarantees ordering for that key. This is the default for most use cases. -

Round-robin: If no key is provided, messages distribute evenly across partitions. This maximizes throughput but provides no ordering guarantees across messages.

Key-based routing is the standard choice. It gives you ordering where you need it (all events for user 123 go to partition 7) while distributing load across the cluster.

Partition Placement

Each partition lives on a broker node. The cluster controller assigns partitions to brokers, balancing the load. A topic with 12 partitions across 4 brokers gets 3 partitions per broker. Each partition has a leader (handles reads and writes) and multiple followers (replicate the leader's log for durability). We cover replication in detail in the deep dive on high availability.

Metadata Management

The cluster needs a central place to track which topics exist, how many partitions each has, and which broker leads each partition. A controller node (or a coordination service like ZooKeeper or an internal Raft-based metadata store) maintains this metadata and distributes it to all brokers and clients.

When a producer connects, it fetches the partition map: "Topic Orders has 12 partitions. Partition 0 is on Broker 3. Partition 1 is on Broker 7..." The producer caches this map and routes messages directly to the correct broker. No intermediary routing layer—producers talk directly to partition leaders.

2. Publish Messages

Producers send messages to a specific topic. The broker appends each message to the appropriate partition's log and replicates it to follower nodes for durability.

The Write Path

When a producer publishes a message, several things happen in sequence:

-

Route to partition. The producer hashes the partition key to determine the target partition. From its cached metadata, it knows which broker leads that partition.

-

Send to leader. The producer sends the message directly to the partition leader. No intermediary—this minimizes latency.

-

Append to WAL. The leader appends the message to the partition's append-only log on disk. This is a sequential write—the message goes to the end of the file. Sequential writes are fast because the disk head doesn't need to seek to random positions. The message receives a monotonically increasing offset (0, 1, 2, 3...) that uniquely identifies its position in the partition.

-

Replicate to followers. The leader sends the message to follower replicas on other brokers. Followers append it to their own copies of the log.

-

Acknowledge. Once the required number of replicas have written the message, the leader sends an acknowledgment back to the producer.

Acknowledgment Modes

The producer can choose how many replicas must confirm the write before the broker acknowledges:

Our choice: acks=all for durability-critical topics. The latency cost is small (typically 1-5ms extra for replication) because followers are writing sequentially to their own disks in parallel.

Batching for Throughput

Sending one message at a time means one network round trip per message. At 500K messages per second, that's 500K round trips—too much overhead.

Producers batch messages. Instead of sending one message immediately, the producer accumulates messages for a short window (roughly 5-10ms or until the batch reaches a size threshold like 64 KB). Then it sends the entire batch in a single network request. The broker appends all messages in the batch to the log in one sequential write.

Batching trades a few milliseconds of latency for dramatically higher throughput. A single 64 KB batch might contain 50-100 messages, reducing network calls by 50-100x.

3. Consume Messages

Consumers read messages from topics. Consumer groups enable both fan-out (multiple services reading the same data) and parallel processing (multiple workers within a service splitting the load).

Pull-Based Consumption

Consumers pull messages from brokers rather than brokers pushing to consumers. Why pull? Each consumer controls its own read rate. A fast analytics consumer can read at 100K messages/second while a slower email consumer reads at 1K/second. With push, the broker would need to track each consumer's capacity and throttle accordingly—complex and fragile.

The consumer sends a fetch request: "Give me messages from partition 3 starting at offset 1042." The broker reads from the partition log and returns a batch of messages. The consumer processes them, then fetches the next batch starting at the new offset.

Consumer Groups

Consumer groups are the mechanism that enables both pub/sub (fan-out) and competing consumers (parallel processing) on the same topic.

Fan-out (Pub/Sub): Each consumer group gets every message. If the "Orders" topic has consumer groups for Analytics, Billing, and Shipping, each group independently reads all messages. The groups don't interfere with each other—each tracks its own offsets.

Parallel processing (Competing Consumers): Within a single consumer group, partitions are divided among consumers. If the Analytics group has 3 consumers and the topic has 6 partitions, each consumer reads from 2 partitions. This splits the work evenly across workers.

The partition-to-consumer rule: Each partition is assigned to exactly one consumer within a group. This is critical for ordering—if two consumers read from the same partition, messages could be processed out of order. One partition, one consumer, strict order maintained.

What happens when consumers change? If a consumer in the group crashes or a new one joins, the group must rebalance—reassign partitions among the remaining consumers. The group coordinator (a designated broker) triggers this:

- All consumers in the group pause and release their partition assignments.

- The coordinator redistributes partitions among active consumers.

- Each consumer resumes reading from its newly assigned partitions at the last committed offset.

Rebalancing causes a brief pause in consumption. During this window, no messages are processed. This is a tradeoff for the simplicity of the one-partition-one-consumer model.

4. Acknowledge and Retain

Consumers signal processing completion by committing offsets. Messages persist for a configurable retention period regardless of consumption status.

Offset Commits

In a traditional AMQP queue, the consumer sends an "ACK" and the broker deletes the message. In a log-based queue, the message stays. Instead, the consumer commits its offset—it tells the broker "I've processed everything up to offset 1042."

The broker stores committed offsets in a durable internal topic (similar to how the system stores any other data). If a consumer crashes and restarts, it asks the broker: "What's my last committed offset for partition 3?" The broker replies "1042," and the consumer resumes from offset 1043.

Commit Strategies

When to commit matters. Commit too early (before processing) and you get at-most-once delivery—crash after commit but before processing, and the message is lost. Commit too late (or not at all) and you reprocess messages unnecessarily after a restart.

Retention Policy

Unlike AMQP queues that delete messages after consumption, log-based queues retain messages by time or size. The retention policy determines when old messages are cleaned up:

-

Time-based: Delete messages older than 7 days. This is the default. Useful when recent data matters but old data becomes irrelevant.

-

Size-based: Delete oldest messages when the partition exceeds a size limit (say 100 GB). This caps storage cost regardless of message rate.

-

Compaction: Keep only the latest message per key. If user 123 has 50 profile update events, keep only the most recent one. This is useful for maintaining a "latest state" log without unbounded growth.

Segment-Based Cleanup

The partition log isn't one giant file. It's split into segments—fixed-size files (roughly 1 GB each). When a segment fills up, the broker creates a new active segment and closes the old one.

Retention works at the segment level. A background thread checks closed segments: if the newest message in a segment is older than the retention period, the entire segment file is deleted. This is efficient—deleting a file is a single OS call, no scanning or rewriting needed.

Why Retention Matters for Replay

Because messages persist beyond consumption, consumers can "rewind" their offset to reprocess old data. If the analytics team deploys a bug fix and needs to recompute the last 3 days of metrics, they reset their consumer group's offset to 3 days ago and replay. No need to re-publish the data. This is impossible with AMQP-style queues where consumed messages are deleted.

Deep Dive Questions

How do you achieve exactly-once delivery, and what are its limits?

A payment service processes an "order completed" message: it charges the customer's credit card, then commits its offset. But the service crashes after the charge succeeds and before the offset commits. The broker sees no commit and redelivers the message. The new consumer instance processes it again—the customer gets charged twice.

This is the fundamental problem with at-least-once delivery. The queue guarantees no message loss, but duplicates are inevitable when failures occur between processing and acknowledgment.

At-Least-Once: The Default

At-least-once is the standard delivery guarantee for log-based message queues. The consumer processes a message, then commits its offset. If it crashes before committing, the broker redelivers. This creates duplicates but never loses messages.

This is simple to implement—just track offsets and retry on failure. Most pipelines (analytics, logging, search indexing, cache invalidation) tolerate duplicates because their operations are naturally idempotent or because occasional duplicates don't matter.

The Side Effect Problem

Before discussing exactly-once, there is a critical distinction. "Exactly-once" in the context of a message queue refers to internal state updates within the queue system. It does not—and cannot—cover external side effects.

Consider this scenario: the consumer reads message M, sends an HTTP call to a payment API that charges the customer, then crashes before committing. The queue redelivers M. The consumer calls the payment API again. The customer is charged twice.

The message queue has no ability to "undo" the first payment API call. It can only control what happens inside its own system—offsets and messages. External side effects (API calls, emails, database writes to external systems) are outside the queue's transaction boundary.

This means: for any operation with external side effects, the consumer must implement idempotency. The queue cannot do it alone.

Consumer-Side Idempotency

The consumer must detect and skip duplicates. Common patterns:

Cooperative Exactly-Once: Internal State Only

For operations that stay entirely within the message queue system—reading from one topic, transforming data, writing to another topic—the queue can provide exactly-once guarantees through atomic transactions.

The pattern: the consumer reads message M from topic A, processes it, produces result R to topic B, and commits its offset on topic A. The queue bundles all three operations (consume offset commit + produce to output topic) into a single atomic transaction. Either all succeed or all roll back.

Practical Guidance

| Guarantee | Data Loss | Duplicates | Complexity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At-most-once | Possible | No | Low | Metrics, logging where gaps are tolerable |

| At-least-once | No | Possible | Medium | Most production pipelines (default choice) |

| Exactly-once (cooperative) | No | No (internal only) | High | Stream processing within the queue; financial pipelines with idempotent consumers |

Most production systems use at-least-once with idempotent consumers. This achieves "effectively-once" semantics with lower complexity than transactional exactly-once. The consumer handles duplicates through deduplication or idempotent operations, and the queue handles retries and offset management.

(For a deeper discussion of delivery guarantees in stream processing, see Delivery Guarantees.)

Grasping the building blocks ("the lego pieces")

This part of the guide will focus on the various components that are often used to construct a system (the building blocks), and the design templates that provide a framework for structuring these blocks.

Core Building blocks

At the bare minimum you should know the core building blocks of system design

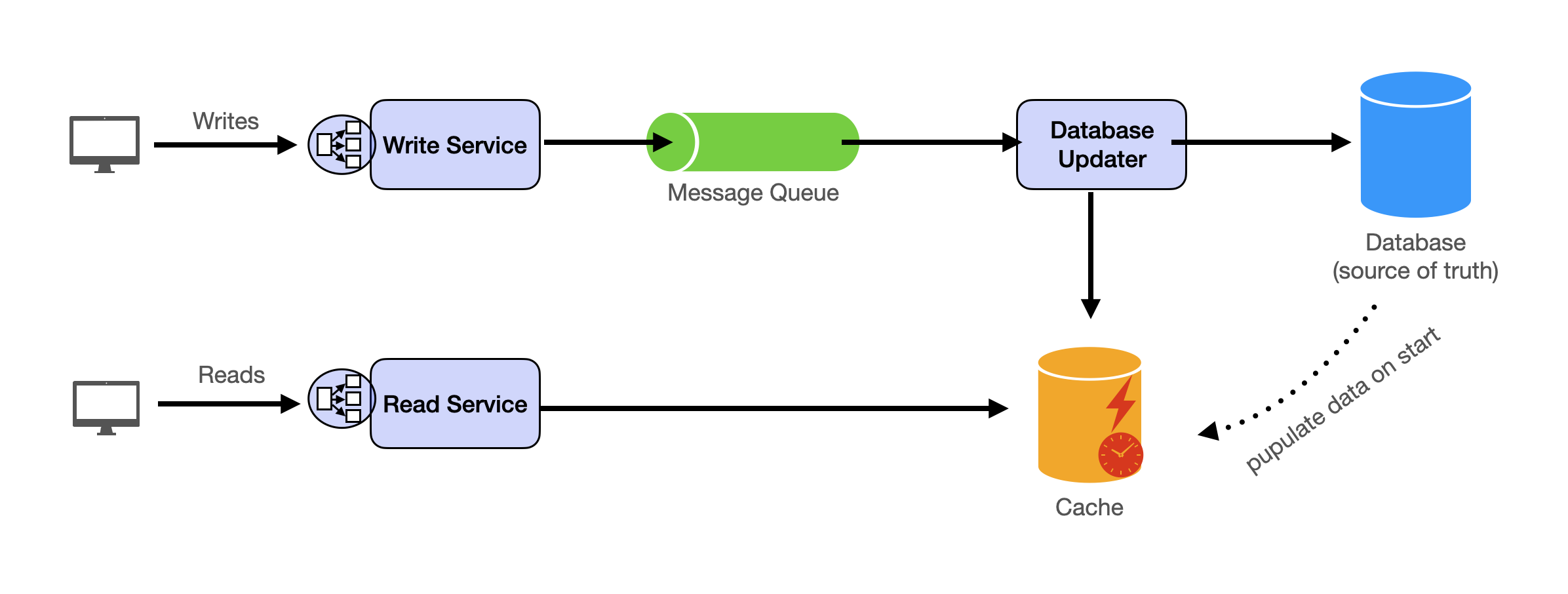

- Scaling stateless services with load balancing

- Scaling database reads with replication and caching

- Scaling database writes with partition (aka sharding)

- Scaling data flow with message queues

System Design Template

With these building blocks, you will be able to apply our template to solve many system design problems. We will dive into the details in the Design Template section. Here’s a sneak peak:

Additional Building Blocks

Additionally, you will want to understand these concepts

- Processing large amount of data (aka “big data”) with batch and stream processing

- Particularly useful for solving data-intensive problems such as designing an analytics app

- Achieving consistency across services using distribution transaction or event sourcing

- Particularly useful for solving problems that require strict transactions such as designing financial apps

- Full text search: full-text index

- Storing data for the long term: data warehousing

On top of these, there are ad hoc knowledge you would want to know tailored to certain problems. For example, geohashing for designing location-based services like Yelp or Uber, operational transform to solve problems like designing Google Doc. You can learn these these on a case-by-case basis. System design interviews are supposed to test your general design skills and not specific knowledge.

Working through problems and building solutions using the building blocks

Finally, we have a series of practical problems for you to work through. You can find the problem in /problems. This hands-on practice will not only help you apply the principles learned but will also enhance your understanding of how to use the building blocks to construct effective solutions. The list of questions grow. We are actively adding more questions to the list.